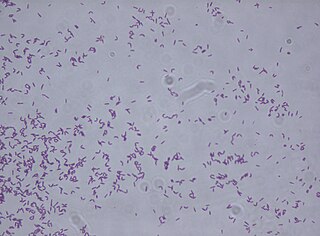

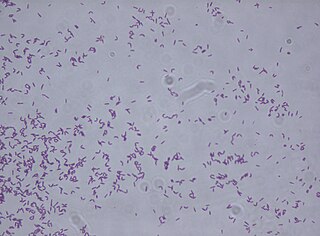

Neisseria gonorrhoeae, also known as gonococcus (singular) or gonococci (plural), is a species of Gram-negative diplococci bacteria isolated by Albert Neisser in 1879. It causes the sexually transmitted genitourinary infection gonorrhea as well as other forms of gonococcal disease including disseminated gonococcemia, septic arthritis, and gonococcal ophthalmia neonatorum.

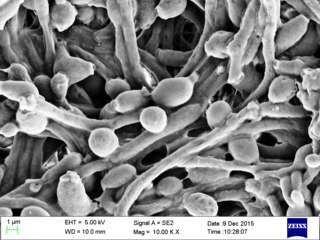

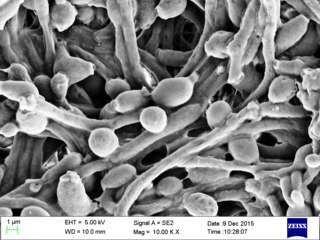

Candida albicans is an opportunistic pathogenic yeast that is a common member of the human gut flora. It can also survive outside the human body. It is detected in the gastrointestinal tract and mouth in 40–60% of healthy adults. It is usually a commensal organism, but it can become pathogenic in immunocompromised individuals under a variety of conditions. It is one of the few species of the genus Candida that cause the human infection candidiasis, which results from an overgrowth of the fungus. Candidiasis is, for example, often observed in HIV-infected patients. C. albicans is the most common fungal species isolated from biofilms either formed on (permanent) implanted medical devices or on human tissue. C. albicans, C. tropicalis, C. parapsilosis, and C. glabrata are together responsible for 50–90% of all cases of candidiasis in humans. A mortality rate of 40% has been reported for patients with systemic candidiasis due to C. albicans. By one estimate, invasive candidiasis contracted in a hospital causes 2,800 to 11,200 deaths yearly in the US. Nevertheless, these numbers may not truly reflect the true extent of damage this organism causes, given new studies indicating that C. albicans can cross the blood–brain barrier in mice.

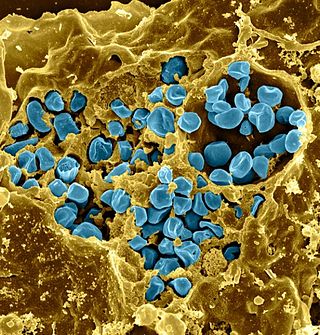

Cryptococcus neoformans is an encapsulated yeast belonging to the class Tremellomycetes and an obligate aerobe that can live in both plants and animals. Its teleomorph is a filamentous fungus, formerly referred to Filobasidiella neoformans. In its yeast state, it is often found in bird excrement. Cryptococcus neoformans can cause disease in apparently immunocompetent, as well as immunocompromised, hosts.

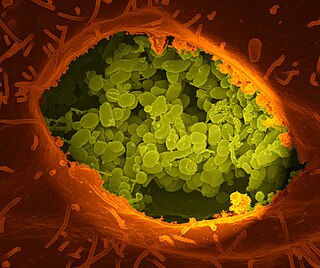

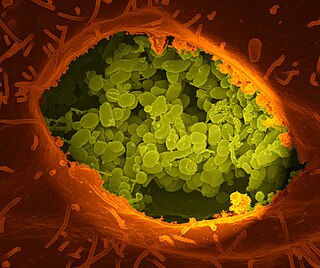

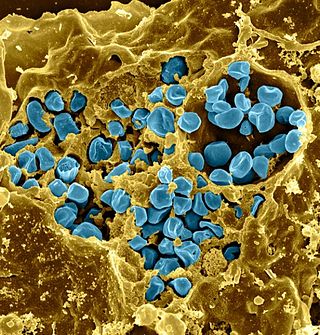

Coxiella burnetii is an obligate intracellular bacterial pathogen, and is the causative agent of Q fever. The genus Coxiella is morphologically similar to Rickettsia, but with a variety of genetic and physiological differences. C. burnetii is a small Gram-negative, coccobacillary bacterium that is highly resistant to environmental stresses such as high temperature, osmotic pressure, and ultraviolet light. These characteristics are attributed to a small cell variant form of the organism that is part of a biphasic developmental cycle, including a more metabolically and replicatively active large cell variant form. It can survive standard disinfectants, and is resistant to many other environmental changes like those presented in the phagolysosome.

Pathogenicity islands (PAIs), as termed in 1990, are a distinct class of genomic islands acquired by microorganisms through horizontal gene transfer. Pathogenicity islands are found in both animal and plant pathogens. Additionally, PAIs are found in both gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria. They are transferred through horizontal gene transfer events such as transfer by a plasmid, phage, or conjugative transposon. Therefore, PAIs contribute to microorganisms' ability to evolve.

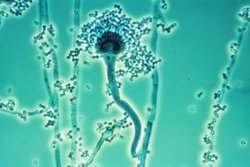

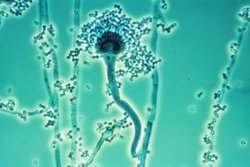

Aspergillus fumigatus is a species of fungus in the genus Aspergillus, and is one of the most common Aspergillus species to cause disease in individuals with an immunodeficiency.

Francisella tularensis is a pathogenic species of Gram-negative coccobacillus, an aerobic bacterium. It is nonspore-forming, nonmotile, and the causative agent of tularemia, the pneumonic form of which is often lethal without treatment. It is a fastidious, facultative intracellular bacterium, which requires cysteine for growth. Due to its low infectious dose, ease of spread by aerosol, and high virulence, F. tularensis is classified as a Tier 1 Select Agent by the U.S. government, along with other potential agents of bioterrorism such as Yersinia pestis, Bacillus anthracis, and Ebola virus. When found in nature, Francisella tularensis can survive for several weeks at low temperatures in animal carcasses, soil, and water. In the laboratory, F. tularensis appears as small rods, and is grown best at 35–37 °C.

Brucella suis is a bacterium that causes swine brucellosis, a zoonosis that affects pigs. The disease typically causes chronic inflammatory lesions in the reproductive organs of susceptible animals or orchitis, and may even affect joints and other organs. The most common symptom is abortion in pregnant susceptible sows at any stage of gestation. Other manifestations are temporary or permanent sterility, lameness, posterior paralysis, spondylitis, and abscess formation. It is transmitted mainly by ingestion of infected tissues or fluids, semen during breeding, and suckling infected animals.

Shigella flexneri is a species of Gram-negative bacteria in the genus Shigella that can cause diarrhea in humans. Several different serogroups of Shigella are described; S. flexneri belongs to group B. S. flexneri infections can usually be treated with antibiotics, although some strains have become resistant. Less severe cases are not usually treated because they become more resistant in the future. Shigella are closely related to Escherichia coli, but can be differentiated from E.coli based on pathogenicity, physiology and serology.

Yersinia pseudotuberculosis is a Gram-negative bacterium that causes Far East scarlet-like fever in humans, who occasionally get infected zoonotically, most often through the food-borne route. Animals are also infected by Y. pseudotuberculosis. The bacterium is urease positive.

In biology, a phagolysosome, or endolysosome, is a cytoplasmic body formed by the fusion of a phagosome with a lysosome in a process that occurs during phagocytosis. Formation of phagolysosomes is essential for the intracellular destruction of microorganisms and pathogens. It takes place when the phagosome's and lysosome's membranes 'collide', at which point the lysosomal contents—including hydrolytic enzymes—are discharged into the phagosome in an explosive manner and digest the particles that the phagosome had ingested. Some products of the digestion are useful materials and are moved into the cytoplasm; others are exported by exocytosis.

Rhodococcus is a genus of aerobic, nonsporulating, nonmotile Gram-positive bacteria closely related to Mycobacterium and Corynebacterium. While a few species are pathogenic, most are benign, and have been found to thrive in a broad range of environments, including soil, water, and eukaryotic cells. Some species have large genomes, including the 9.7 megabasepair genome of Rhodococcus sp. RHA1.

Rhodococcus fascians is a Gram positive bacterial phytopathogen that causes leafy gall disease. R. fascians is the only phytopathogenic member of the genus Rhodococcus; its host range includes both dicotyledonous and monocotyledonous hosts. Because it commonly afflicts tobacco (Nicotiana) plants, it is an agriculturally significant pathogen.

Listeriolysin O (LLO) is a hemolysin produced by the bacterium Listeria monocytogenes, the pathogen responsible for causing listeriosis. The toxin may be considered a virulence factor, since it is crucial for the virulence of L. monocytogenes.

Virulence-related outer membrane proteins, or outer surface proteins (Osp) in some contexts, are expressed in the outer membrane of gram-negative bacteria and are essential to bacterial survival within macrophages and for eukaryotic cell invasion.

Bacillus anthracis is a gram-positive and rod-shaped bacterium that causes anthrax, a deadly disease to livestock and, occasionally, to humans. It is the only permanent (obligate) pathogen within the genus Bacillus. Its infection is a type of zoonosis, as it is transmitted from animals to humans. It was discovered by a German physician Robert Koch in 1876, and became the first bacterium to be experimentally shown as a pathogen. The discovery was also the first scientific evidence for the germ theory of diseases.

Streptococcus zooepidemicus is a Lancefield group C streptococcus that was first isolated in 1934 by P. R. Edwards, and named Animal pyogens A. It is a mucosal commensal and opportunistic pathogen that infects several animals and humans, but most commonly isolated from the uterus of mares. It is a subspecies of Streptococcus equi, a contagious upper respiratory tract infection of horses, and shares greater than 98% DNA homology, as well as many of the same virulence factors.

Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica is a subspecies of Salmonella enterica, the rod-shaped, flagellated, aerobic, Gram-negative bacterium. Many of the pathogenic serovars of the S. enterica species are in this subspecies, including that responsible for typhoid.

Vibrio anguillarum is a species of prokaryote that belongs to the family Vibrionaceae, genus Vibrio. V. anguillarum is typically 0.5 - 1 μm in diameter and 1 - 3 μm in length. It is a gram-negative, comma-shaped rod bacterium that is commonly found in seawater and brackish waters. It is polarly flagellated, non-spore-forming, halophilic, and facultatively anaerobic. V. anguillarum has the ability to form biofilms. V. anguillarum is pathogenic to various fish species, crustaceans, and mollusks.

Listeria ivanovii is a species of bacteria in the genus Listeria. The listeria are rod-shaped bacteria, do not produce spores, and become positively stained when subjected to Gram staining. Of the six bacteria species within the genus, L. ivanovii is one of the two pathogenic species. In 1955 Bulgaria, the first known isolation of this species was found from sheep. It behaves like L. monocytogenes, but is found almost exclusively in ruminants. The species is named in honor of Bulgarian microbiologist Ivan Ivanov. This species is facultatively anaerobic, which makes it possible for it to go through fermentation when there is oxygen depletion.