The denarius was the standard Roman silver coin from its introduction in the Second Punic War c. 211 BC to the reign of Gordian III, when it was gradually replaced by the antoninianus. It continued to be minted in very small quantities, likely for ceremonial purposes, until and through the Tetrarchy (293–313).

Electrum is a naturally occurring alloy of gold and silver, with trace amounts of copper and other metals. Its color ranges from pale to bright yellow, depending on the proportions of gold and silver. It has been produced artificially and is also known as "green gold".

The as, occasionally assarius, was a bronze, and later copper, coin used during the Roman Republic and Roman Empire.

The sestertius or sesterce was an ancient Roman coin. During the Roman Republic it was a small, silver coin issued only on rare occasions. During the Roman Empire it was a large brass coin.

Roman currency for most of Roman history consisted of gold, silver, bronze, orichalcum and copper coinage. From its introduction during the Republic, in the third century BC, through Imperial times, Roman currency saw many changes in form, denomination, and composition. A persistent feature was the inflationary debasement and replacement of coins over the centuries. Notable examples of this followed the reforms of Diocletian. This trend continued with Byzantine currency.

Byzantine currency, money used in the Eastern Roman Empire after the fall of the West, consisted of mainly two types of coins: the gold solidus and a variety of clearly valued bronze coins. By the end of the empire the currency was issued only in silver stavrata and minor copper coins with no gold issue.

The semis was a small Roman bronze coin that was valued at half an as. During the Roman Republic, the semis was distinguished by an 'S' or 6 dots. Some of the coins featured a bust of Saturn on the obverse, and the prow of a ship on the reverse.

The bes was an Ancient Roman bronze coin produced during the Roman Republic. Valued at two thirds of an as, it was only produced in 126 BC by C. Cassius in combination with the dodrans, another very rare denomination which was valued at three quarters of an as. The obverse head displayed the god Liber facing to the right.

The uncia was a Roman currency worth one twelfth of an as.

Roman Republican currency is the coinage struck by the various magistrates of the Roman Republic, to be used as legal tender. In modern times, the abbreviation RRC, "Roman Republican Coinage" originally the name of a reference work on the topic by Michael H. Crawford, has come to be used as an identifying tag for coins assigned a number in that work, such as RRC 367.

The Coinage of India began anywhere between early 1st millennium BCE to the 6th century BCE, and consisted mainly of copper and silver coins in its initial stage. The coins of this period were Karshapanas or Pana. A variety of earliest Indian coins, however, unlike those circulated in West Asia, were stamped bars of metal, suggesting that the innovation of stamped currency was added to a pre-existing form of token currency which had already been present in the Janapadas and Mahajanapada kingdoms of the Early historic India. The kingdoms that minted their own coins included Gandhara, Kuntala, Kuru, Magadha, Panchala, Shakya, Surasena, Surashtra and Vidarbha etc.

This glossary of numismatics is a list of definitions of terms and concepts relevant to numismatics and coin collecting, as well as sub-fields and related disciplines, with concise explanations for the beginner or professional.

Aksumite currency was coinage produced and used within the Kingdom of Aksum centered in present-day Eritrea and Ethiopia. Its mintages were issued and circulated from the reign of King Endubis around AD 270 until it began its decline in the first half of the 7th century where they started using Dinar along with most parts of the Middle East. During the succeeding medieval period, Mogadishu currency, minted by the Sultanate of Mogadishu, was the most widely circulated currency in eastern and souther part Horn of Africa from the start of the 12th century.

The dodrans or nonuncium was an Ancient Roman bronze coin produced during the Roman Republic.

Aes grave is a term in numismatics indicating bronze cast coins used in central Italy during the 3rd century BC, whose value was generally indicated by signs: I for the as, S for semis and pellets for unciae. Standard weights for the as were 272, 327, or 341 grams, depending upon the issuing authority.

Like the Egyptians, Phoenicians and Carthaginians, the Etruscans were rather slow to adopt the invention of coinage. The brief period of Etruscan coinage, with the predominance of marks of value, seems to be an amalgam that reconciles two very different monetary systems: the 'primitive' bronze-weighing and aes grave economy of central Italy with that of struck silver and gold issues of southern Italian Greek type not familiar in Etruria.

Aes signatum consisted of cast ingots of bronze of measured quality and weight, embossed with a government stamp, used as currency in Rome and central Italy starting in the 5th century BC before the introduction of aes grave in the mid 3rd century BC. When exactly they were first made is uncertain. Popular tradition ascribes them to Servius Tullius, but due to the high quality of art found on even the earliest specimens, this seems very unlikely. A date in the midst of the 5th century BC is generally agreed on. Designs featured are that of a bull, an eagle, and other religious symbols.

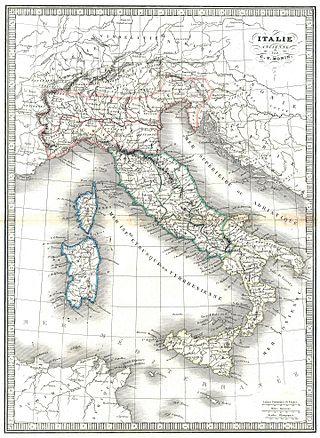

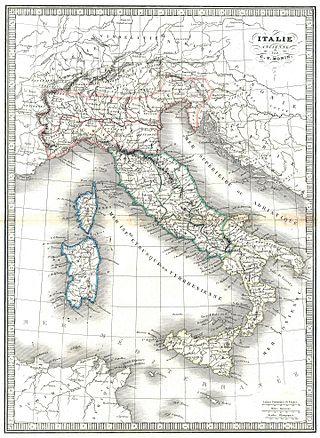

Italy has a long history of different coinage types, which spans thousands of years. Italy has been influential at a coinage point of view: the medieval Florentine florin, one of the most used coinage types in European history and one of the most important coins in Western history, was struck in Florence in the 13th century, while the Venetian sequin, minted from 1284 to 1797, was the most prestigious gold coin in circulation in the commercial centers of the Mediterranean Sea.

The coinage reform of Augustus refers to the reform of Roman currency undertaken by Augustus in 23 BC.

The coinage of Capua concerns coins minted in ancient Capua, a city in ancient Campania, corresponding to present-day Santa Maria Capua Vetere. The city was located on the Appian Way and was the most important in the area, probably the largest center in the Italian peninsula after Rome.