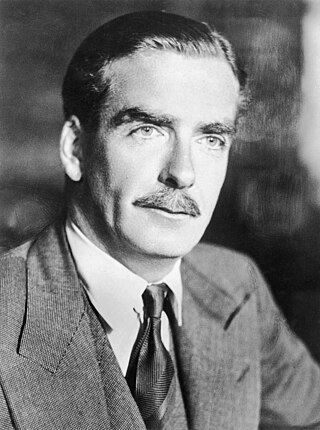

R. A. C. Parker | |

|---|---|

| Born | Robert Alexander Clarke Parker 15 June 1927 |

| Died | 23 April 2001 (aged 73) |

| Spouse | Julia Dixon |

| Academic background | |

| Alma mater | |

| Academic work | |

| Discipline | History |

| Institutions |

|

| Main interests | Appeasement |

Robert Alexander Clarke Parker (15 June 1927 - 23 April 2001) was a British historian who specialised in Britain's appeasement of Nazi Germany and the Second World War. Fellow historian Kenneth O. Morgan called him "perhaps the leading authority on the international crises of the 1930s,appeasement and the coming of war". [1]

He was born in Barnsley,Yorkshire to a family with a Scottish roots,which Parker was proud of;he changed his first name to Alastair. [1] He served in the Royal Navy during the Second World War and after the war's end he won a scholarship to Christ Church,Oxford. He studied modern history,for which he gained a First. For his doctoral thesis,Parker studied Coke of Norfolk and the British Agricultural Revolution. This was eventually published in 1975. [1]

In 1952 Lewis Namier appointed Parker to a lectureship in history at Manchester University,a post he held until 1957. From 1957 until his retirement in 1997,he was a Fellow and tutor at The Queen's College,Oxford. [1] His main area of historical study was Neville Chamberlain,Winston Churchill and the appeasement of Germany. He taught a special subject on the origins of the Second World War at The Queen's College. [1]

In his 1997 work,Chamberlain and Appeasement,Parker argued that Chamberlain did not pursue appeasement in order to buy time,as some of his defenders claimed. He added that Churchill's alternative strategy of an Anglo-French alliance was a realistic and more honourable course. [1] In his last book,Churchill and Appeasement (2000),Parker noted what he considered to be Churchill's misjudgments over India and the Spanish Civil War but said Churchill was completely right on the threat from Nazi Germany. Churchill's proposal of an Anglo-Soviet alliance may well have deterred Adolf Hitler if it had been adopted,Parker claimed. [1] He edited a collection of essays on Churchill which were published in 1995. [1]

Parker held Old Labour political views and canvassed for the Labour Party at elections. [1]

Arthur Neville Chamberlain was a British politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from May 1937 to May 1940 and Leader of the Conservative Party from May 1937 to October 1940. He is best known for his foreign policy of appeasement, and in particular for his signing of the Munich Agreement on 30 September 1938, ceding the German-speaking Sudetenland region of Czechoslovakia to Nazi Germany led by Adolf Hitler. Following the invasion of Poland on 1 September 1939, which marked the beginning of the Second World War, Chamberlain announced the declaration of war on Germany two days later and led the United Kingdom through the first eight months of the war until his resignation as prime minister on 10 May 1940.

The Munich Agreement was an agreement reached in Munich on 30 September 1938, by Nazi Germany, the United Kingdom, the French Republic, and Fascist Italy. The agreement provided for the German annexation of part of Czechoslovakia called the Sudetenland, where more than three million people, mainly ethnic Germans, lived. The pact is also known in some areas as the Munich Betrayal, because of a previous 1924 alliance agreement and a 1925 military pact between France and the Czechoslovak Republic.

Alfred Leslie Rowse was a British historian and writer, best known for his work on Elizabethan England and books relating to Cornwall.

Appeasement, in an international context, is a diplomatic negotiation policy of making political, material, or territorial concessions to an aggressive power with intention to avoid conflict. The term is most often applied to the foreign policy between 1935 and 1939 of the British governments of Prime Ministers Ramsay MacDonald, Stanley Baldwin and most notably Neville Chamberlain towards Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy. Under British pressure, appeasement of Nazism and Fascism also played a role in French foreign policy of the period but was always much less popular there than in the United Kingdom.

Edward Frederick Lindley Wood, 1st Earl of Halifax,, known as the Lord Irwin from 1925 until 1934 and the Viscount Halifax from 1934 until 1944, was a senior British Conservative politician of the 1930s. He held several senior ministerial posts during this time, most notably those of Viceroy of India from 1926 to 1931 and of Foreign Secretary between 1938 and 1940. He was one of the architects of the policy of appeasement of Adolf Hitler in 1936–1938, working closely with Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain. After Kristallnacht on 9–10 November 1938 and the German occupation of Czechoslovakia in March 1939, he was one of those who pushed for a new policy of attempting to deter further German aggression by promising to go to war to defend Poland.

Sir Richard Stafford Cripps was a British Labour Party politician, barrister, and diplomat.

Edward Hugh John Neale Dalton, Baron Dalton, was a British Labour Party economist and politician who served as Chancellor of the Exchequer from 1945 to 1947. He shaped Labour Party foreign policy in the 1930s, opposing pacifism; promoting rearmament against the German threat; and strongly opposed the appeasement policy of Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain in 1938. Dalton served in Winston Churchill's wartime coalition cabinet; after the Dunkirk evacuation he was Minister of Economic Warfare, and established Special Operations Executive. As Chancellor, he pushed his policy of cheap money too hard, and mishandled the sterling crisis of 1947. His political position was already in jeopardy in 1947 when he, seemingly inadvertently, revealed a sentence of the budget to a reporter minutes before delivering his budget speech. Prime Minister Clement Attlee accepted his resignation; Dalton later returned to the cabinet in relatively minor positions.

Guilty Men is a British polemical book written under the pseudonym "Cato" that was published in July 1940, after the failure of British forces to prevent the defeat and occupation of Norway and France by Nazi Germany. It attacked fifteen public figures for their failed policies towards Germany and for their failure to re-equip the British armed forces. In denouncing appeasement, it defined the policy as the "deliberate surrender of small nations in the face of Hitler's blatant bullying". A classic denunciation of the former government's policy, it shaped popular and scholarly thinking for the next two decades.

Why England Slept (1940) is the published version of a thesis written by John F. Kennedy in his senior year at Harvard College. Its title alludes to Winston Churchill's 1938 book Arms and the Covenant, published in the United States as While England Slept, which also examined the buildup of German power. Kennedy's book examines the failures of the British government to take steps to prevent World War II and its initial lack of response to Adolf Hitler's threats of war.

Sir Horace John Wilson, was a senior British government official who had a key role, as Head of the Home Civil Service, with government of Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain in the appeasement period just prior to the Second World War.

Ivan Mikhailovich Maisky was a Soviet diplomat, historian and politician who served as the Soviet Union's ambassador to the United Kingdom from 1932 to 1943, including much of the period of the Second World War.

Sir Nevile Meyrick Henderson was a British diplomat who served as the ambassador of the United Kingdom to Germany from 1937 to 1939.

Shiela Grant Duff was a British author, journalist and foreign correspondent. She was known for her opposition to appeasement before the Second World War.

Robert Anthony Eden, 1st Earl of Avon, was a British politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom and Leader of the Conservative Party from 1955 until his resignation in 1957.

Colonel Wilfrid William Ashley, 1st Baron Mount Temple, PC DL was a British soldier and Conservative politician. He was Minister of Transport between 1924 and 1929 under Stanley Baldwin.

Frank McDonough is a British historian of the Third Reich and international history.

The European foreign policy of the Chamberlain ministry from 1937 to 1940 was based on British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain's commitment to "peace for our time" by pursuing a policy of appeasement and containment towards Nazi Germany and by increasing the strength of Britain's armed forces until, in September 1939, he delivered an ultimatum over the invasion of Poland, which was followed by a declaration of war against Germany.

A Total and Unmitigated Defeat was a speech by Winston Churchill in the House of Commons at Westminster on Wednesday, 5 October 1938, the third day of the Munich Agreement debate. Signed five days earlier by Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain, the agreement met the demands of Nazi Germany in respect of the Czechoslovak region of Sudetenland.

Richard Austen Butler, generally known as R. A. Butler and familiarly known from his initials as Rab, was a prominent British Conservative Party politician.

When Britain emerged victorious from the Second World War, the Labour Party under Clement Attlee came to power and created a comprehensive welfare state, with the establishment of the National Health Service giving free healthcare to all British citizens, and other reforms to benefits. The Bank of England, railways, heavy industry, and coal mining were all nationalised. Unlike the others, the most controversial issue was nationalisation of steel, which was profitable. Economic recovery was slow, housing was in short supply, and bread was rationed along with many necessities in short supply. It was an "age of austerity". American loans and Marshall Plan grants kept the economy afloat. India, Pakistan, Burma, and Ceylon gained independence. Britain was a strong anti-Soviet factor in the Cold War and helped found NATO in 1949. Many historians describe this era as the "post-war consensus", emphasising how both the Labour and Conservative Parties until the 1970s tolerated or encouraged nationalisation, strong trade unions, heavy regulation, high taxes, and generous welfare state.