Racial color blindness refers to the belief that a person's race or ethnicity should not influence their legal or social treatment in society.

Feminist sociology is an interdisciplinary exploration of gender and power throughout society. Here, it uses conflict theory and theoretical perspectives to observe gender in its relation to power, both at the level of face-to-face interaction and reflexivity within social structures at large. Focuses include sexual orientation, race, economic status, and nationality.

Patricia Hill Collins is an American academic specializing in race, class, and gender. She is a distinguished university professor of sociology emerita at the University of Maryland, College Park. She is also the former head of the Department of African-American Studies at the University of Cincinnati. Collins was elected president of the American Sociological Association (ASA), and served in 2009 as the 100th president of the association – the first African-American woman to hold this position.

Barbara Jeanne Fields is an American historian. She is a professor of American history at Columbia University. Her focus is on the history of the American South, 19th century social history, and the transition to capitalism in the United States.

Reverse racism, sometimes referred to as reverse discrimination, is the concept that affirmative action and similar color-conscious programs for redressing racial inequality are forms of anti-white racism. The concept is often associated with conservative social movements and reflects a belief that social and economic gains by Black people and other people of color cause disadvantages for white people.

Sexual capital or erotic capital is the social power an individual or group accrues as a result of their sexual attractiveness and social charm. It enables social mobility independent of class origin because sexual capital is convertible, and may be useful in acquiring other forms of capital, including social capital and economic capital.

Howard Winant is an American sociologist and race theorist. Winant is Distinguished Professor of Sociology at the University of California, Santa Barbara. Winant is best known for developing the theory of racial formation along with Michael Omi. Winant's research and teachings revolve around race and racism, comparative historical sociology, political sociology, social theory, and human rights.

France Winddance Twine is a Black and Native American sociologist, ethnographer, visual artist, and documentary filmmaker. Twine has conducted field research in Brazil, the UK, and the United States on race, racism, and anti-racism. She has published 11 books and more than 100 articles, review essays, and books on these topics.

Oliver Cromwell Cox was a Trinidadian-American sociologist. Cox was often misconceived as a Marxist due to his focus on class conflict and capitalism, however, Cox fundamentally disagreed with Marx's analysis of Capitalism. While Marx and other classical economists viewed foreign trade as trade in surpluses, Cox felt that foreign trade was the primary driving force in capitalist development. For Cox, capitalist systems were not isolated, but rather there was an interconnected network of global capitalist systems.

The Racial Contract is a book by the Jamaican philosopher Charles W. Mills in which he shows that, although it is conventional to represent the social contract moral and political theories of Thomas Hobbes, John Locke, Jean-Jacques Rousseau, and Immanuel Kant as neutral with respect to race and ethnicity, in actuality, the philosophers understood them to regulate only relations between whites; in relation to non-whites, these philosophers helped to create a "racial contract", which in both formal and informal ways permitted whites to oppress and exploit non-whites and validate their own moral ideals in dealing with non-whites. Because in contemporary political philosophy, white philosophers take their own white privilege for granted, they don't recognize that white supremacy is a political system, and so in their developments of ideal, moral and political theory never consider actual practice. Mills proposes to develop a non-ideal theory "to explain and expose the inequities of the actual nonideal policy and to help us see through the theories and moral justifications offered in defense of them." Using it as a central concept, "the notion of a Racial Contract might be more revealing of the real character of the world we are living in, and the corresponding historical deficiencies of its normative theories and practices, than the raceless notions currently dominant in political theory." The book has been translated into various languages.

The sociology of race and ethnic relations is the study of social, political, and economic relations between races and ethnicities at all levels of society. This area encompasses the study of systemic racism, like residential segregation and other complex social processes between different racial and ethnic groups.

Why Marx Was Right is a 2011 non-fiction book by the British academic Terry Eagleton about the 19th-century philosopher Karl Marx and the schools of thought, collectively known as Marxism, that arose from his work. Written for laypeople, Why Marx Was Right outlines ten objections to Marxism that they may hold and aims to refute each one in turn. These include arguments that Marxism is irrelevant owing to changing social classes in the modern world, that it is deterministic and utopian, and that Marxists oppose all reforms and believe in an authoritarian state.

Racism without Racists: Color-Blind Racism and the Persistence of Racial Inequality in the United States is a book about color-blind racism in the United States by Eduardo Bonilla-Silva, a sociology professor at Duke University. It was originally published by Rowman & Littlefield in 2003, and has since been re-published four times, most recently in June 2017. The fourth edition was published soon after Barack Obama's election, and includes a new chapter on what Bonilla-Silva calls "the new racism". It was reviewed favorably in Science & Society, Urban Education, Educational Studies, and Multicultural Perspectives.

Crystal Marie Fleming is an American sociologist and author. She is full professor of sociology and Africana studies at Stony Brook University. Fleming is the author/editor of four books about race and white supremacy.

Zine Magubane is a scholar whose work focuses broadly on the intersections of gender, sexuality, race, and post-colonial studies in the United States and Southern Africa. She has held professorial positions at various academic institutions in the United States and South Africa and has published several articles and books.

Racial capitalism is a concept reframing the history of capitalism as grounded in the extraction of social and economic value from people of marginalized racial identities, typically from Black people. It was described by Cedric J. Robinson in his book Black Marxism: The Making of the Black Radical Tradition, published in 1983, which, in contrast to both his predecessors and successors, theorized that all capitalism is inherently racial capitalism, and racialism is present in all layers of capitalism's socioeconomic stratification. Jodi Melamed has summarized the concept, explaining that capitalism "can only accumulate by producing and moving through relations of severe inequality among human groups", and therefore, for capitalism to survive, it must exploit and prey upon the "unequal differentiation of human value."

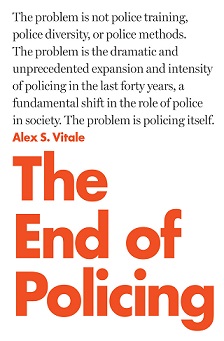

The End of Policing is a 2017 book by the American sociologist Alex S. Vitale. In it, Vitale argues for the eventual abolition of the police, to be replaced variously by decriminalization or with non-law enforcement approaches, depending on the crime. Vitale argues that the function of police is to uphold inequalities of class, gender, race, or sexuality.

Anne Warfield Rawls is an American sociologist, social theorist and ethnomethodologist. She is Professor of Sociology at Bentley University, Professor for Interaction, Work and Information at the University of Siegen, Germany and Director of the Harold Garfinkel Archive, Newburyport, MA. Rawls has been teaching courses on social theory, social interaction, ethnomethodology and systemic racism for over forty years. She has also written extensively on Émile Durkheim and Harold Garfinkel, explaining their argument that equality is needed to ground practices in democratic publics, and showing how inequality interferes with the cooperation and reflexivity necessary to successfully engage in complex practices.

Karen E. Fields is an American sociologist. She is the sister of historian Barbara J. Fields.

Race and Racism: A Comparative Perspective is a 1967 non-fiction book by Pierre L. van den Berghe, published by John Wiley & Sons.