The Advanced Encryption Standard (AES), also known by its original name Rijndael, is a specification for the encryption of electronic data established by the U.S. National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) in 2001.

In cryptography, an HMAC is a specific type of message authentication code (MAC) involving a cryptographic hash function and a secret cryptographic key. As with any MAC, it may be used to simultaneously verify both the data integrity and authenticity of a message. An HMAC is a type of keyed hash function that can also be used in a key derivation scheme or a key stretching scheme.

The MD5 message-digest algorithm is a widely used hash function producing a 128-bit hash value. MD5 was designed by Ronald Rivest in 1991 to replace an earlier hash function MD4, and was specified in 1992 as RFC 1321.

In cryptography, SHA-1 is a hash function which takes an input and produces a 160-bit (20-byte) hash value known as a message digest – typically rendered as 40 hexadecimal digits. It was designed by the United States National Security Agency, and is a U.S. Federal Information Processing Standard. The algorithm has been cryptographically broken but is still widely used.

A cryptographic hash function (CHF) is a hash algorithm that has special properties desirable for a cryptographic application:

In computer science and cryptography, Whirlpool is a cryptographic hash function. It was designed by Vincent Rijmen and Paulo S. L. M. Barreto, who first described it in 2000.

The MD4 Message-Digest Algorithm is a cryptographic hash function developed by Ronald Rivest in 1990. The digest length is 128 bits. The algorithm has influenced later designs, such as the MD5, SHA-1 and RIPEMD algorithms. The initialism "MD" stands for "Message Digest".

The Secure Hash Algorithms are a family of cryptographic hash functions published by the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) as a U.S. Federal Information Processing Standard (FIPS), including:

SHA-2 is a set of cryptographic hash functions designed by the United States National Security Agency (NSA) and first published in 2001. They are built using the Merkle–Damgård construction, from a one-way compression function itself built using the Davies–Meyer structure from a specialized block cipher.

Panama is a cryptographic primitive which can be used both as a hash function and a stream cipher, but its hash function mode of operation has been broken and is not suitable for cryptographic use. Based on StepRightUp, it was designed by Joan Daemen and Craig Clapp and presented in the paper Fast Hashing and Stream Encryption with PANAMA on the Fast Software Encryption (FSE) conference 1998. The cipher has influenced several other designs, for example MUGI and SHA-3.

Skein is a cryptographic hash function and one of five finalists in the NIST hash function competition. Entered as a candidate to become the SHA-3 standard, the successor of SHA-1 and SHA-2, it ultimately lost to NIST hash candidate Keccak.

SHA-3 is the latest member of the Secure Hash Algorithm family of standards, released by NIST on August 5, 2015. Although part of the same series of standards, SHA-3 is internally different from the MD5-like structure of SHA-1 and SHA-2.

The following tables compare general and technical information for a number of cryptographic hash functions. See the individual functions' articles for further information. This article is not all-inclusive or necessarily up-to-date. An overview of hash function security/cryptanalysis can be found at hash function security summary.

The following outline is provided as an overview of and topical guide to cryptography:

MurmurHash is a non-cryptographic hash function suitable for general hash-based lookup. It was created by Austin Appleby in 2008 and is currently hosted on GitHub along with its test suite named 'SMHasher'. It also exists in a number of variants, all of which have been released into the public domain. The name comes from two basic operations, multiply (MU) and rotate (R), used in its inner loop.

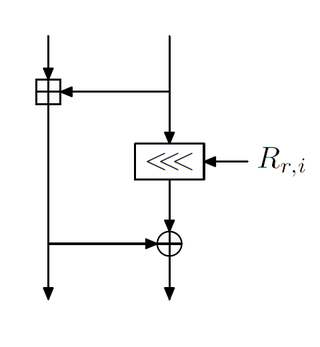

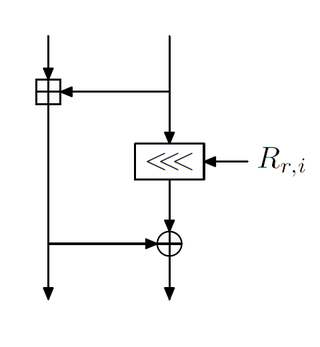

In cryptography, rotational cryptanalysis is a generic cryptanalytic attack against algorithms that rely on three operations: modular addition, rotation and XOR — ARX for short. Algorithms relying on these operations are popular because they are relatively cheap in both hardware and software and run in constant time, making them safe from timing attacks in common implementations.

This article summarizes publicly known attacks against cryptographic hash functions. Note that not all entries may be up to date. For a summary of other hash function parameters, see comparison of cryptographic hash functions.

In cryptography, a sponge function or sponge construction is any of a class of algorithms with finite internal state that take an input bit stream of any length and produce an output bit stream of any desired length. Sponge functions have both theoretical and practical uses. They can be used to model or implement many cryptographic primitives, including cryptographic hashes, message authentication codes, mask generation functions, stream ciphers, pseudo-random number generators, and authenticated encryption.

Speck is a family of lightweight block ciphers publicly released by the National Security Agency (NSA) in June 2013. Speck has been optimized for performance in software implementations, while its sister algorithm, Simon, has been optimized for hardware implementations. Speck is an add–rotate–xor (ARX) cipher.

Dmitry Khovratovich is a Russian cryptographer, currently a Lead Cryptographer for the Dusk Network, researcher for the Ethereum Foundation, and member of the International Association for Cryptologic Research.