The Nationalist Party, also known as the National Party, was an Australian political party. It was formed in February 1917 from a merger between the Liberal Party and the National Labor Party, the latter formed by Prime Minister Billy Hughes and his supporters after the 1916 Labor Party split over World War I conscription. The Nationalist Party was established as a 'united' non-Labor opposition that had remained a political trend once the Labor party established itself in federal politics. The party was in government until electoral defeat in 1929. From that time it was the main opposition to the Labor Party until it merged with pro-Joseph Lyons Labor defectors to form the United Australia Party (UAP) in 1931. The party is a direct ancestor of the Liberal Party of Australia, the main centre-right party in Australia.

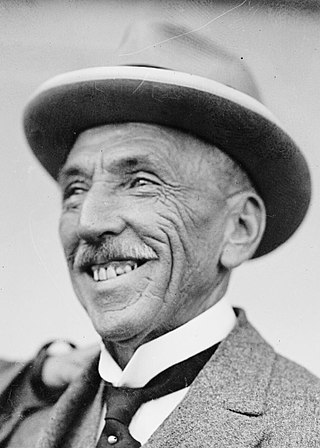

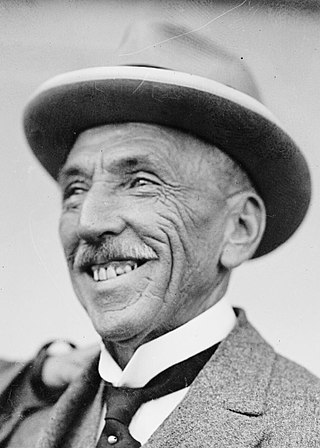

William Morris Hughes was an Australian politician who served as the seventh prime minister of Australia from 1915 to 1923. He is best known for leading the country during World War I, but his influence on national politics spanned several decades. Hughes was a member of federal parliament from Federation in 1901 until his death in 1952, the only person to have served for more than 50 years. He represented six political parties during his career, leading five, outlasting four, and being expelled from three.

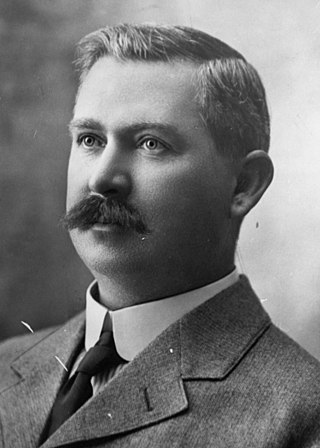

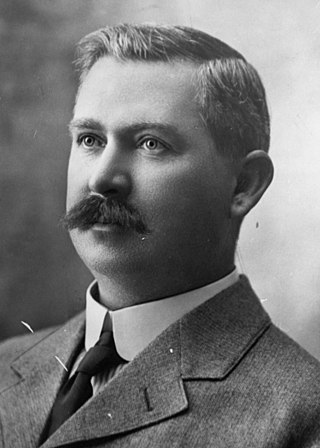

Francis Gwynne Tudor was an Australian politician who served as the leader of the Australian Labor Party from 1916 until his death. He had previously been a government minister under Andrew Fisher and Billy Hughes.

Conscription in Australia, also known as National Service following the Second World War, has a controversial history which dates back to the implementation of compulsory military training and service in the first years of Australia's nationhood. Military conscription for peacetime service was abolished in 1972.

The National Labor Party was formed by Australian Prime Minister Billy Hughes in 1916, following the 1916 Labor split on the issue of World War I conscription in Australia. Hughes had taken over as leader of the Australian Labor Party and Prime Minister of Australia when anti-conscriptionist Andrew Fisher resigned in 1915. He formed the new party for himself and his followers after he was expelled from the ALP a month after the 1916 plebiscite on conscription in Australia. Hughes held a pro-conscription stance in relation to World War I.

In Australia, referendums are public votes held on important issues where the electorate may approve or reject a certain proposal. In contemporary usage, polls conducted on non-constitutional issues are known as plebiscites, with the term referendum being reserved solely for votes on constitutional changes, which is legally required to make a change to the Constitution of Australia.

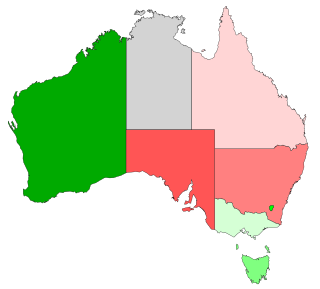

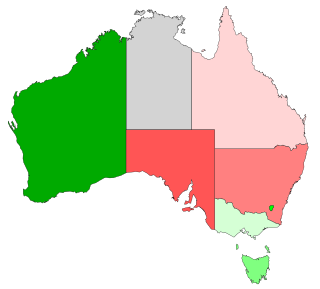

The 1916 Australian referendum, concerning how conscripted soldiers could be deployed, was held on 28 October 1916. It was the first non-binding Australian referendum, and contained one proposition, which was Prime Minister Billy Hughes' proposal to allow conscripted troops to serve overseas during World War I.

The 1917 Australian referendum was held on 20 December 1917. It contained one question.

The 1917 Australian federal election was held in Australia on 5 May 1917. All 75 seats in the House of Representatives and 18 of the 36 seats in the Senate were up for election. The incumbent Nationalist Party, led by Prime Minister Billy Hughes, defeated the opposition Labor Party led by Frank Tudor in a landslide.

Henry Thomas Givens was an Australian politician. He served as a Senator for Queensland from 1904 until his death in 1928 and was President of the Senate from 1913 to 1926. He began his career in the Australian Labor Party (ALP), serving briefly in the Queensland Legislative Assembly (1899–1902), but became a Nationalist after the party split of 1916. He was born in Ireland and worked as a labourer, miner, trade unionist and newspaper editor before entering politics.

During the second half of World War I, the First Australian Imperial Force experienced a shortage of men as the number of men volunteering to fight overseas declined and the casualty rate increased. At the time, military service within the Commonwealth of Australia and its territories was compulsory for Australian men, but that requirement did not extend to conflict outside of Australia. In 1916, Prime Minister Billy Hughes called a plebiscite to determine public support for extending conscription to include military service outside the Commonwealth for the duration of the war. The referendum, held on 28 October 1916, narrowly rejected the proposal. A second plebiscite, held a year later on 20 December 1917, also failed to gain a majority.

Thomas Joseph Ryan was an Australian politician who served as Premier of Queensland from 1915 to 1919, as leader of the state Labor Party. He resigned to enter federal politics, sitting in the House of Representatives for the federal Labor Party from 1919 until his premature death less than two years later.

The history of the Australian Labor Party has its origins in the Labour parties founded in the 1890s in the Australian colonies prior to federation. Labor tradition ascribes the founding of Queensland Labour to a meeting of striking pastoral workers under a ghost gum tree in Barcaldine, Queensland in 1891. The Balmain, New South Wales branch of the party claims to be the oldest in Australia. Labour as a parliamentary party dates from 1891 in New South Wales and South Australia, 1893 in Queensland, and later in the other colonies.

Jeremiah Joseph Stable (1883–1953) was the first professor of English at the University of Queensland in Brisbane, Queensland, Australia.

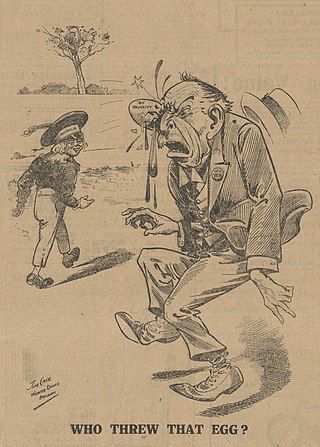

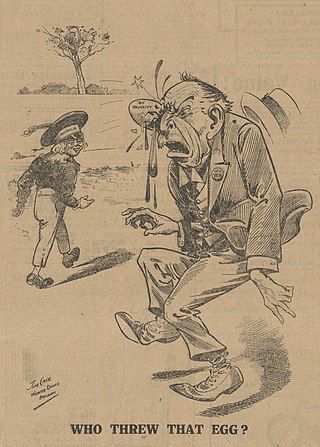

On 29 November 1917, an egg was thrown at the Australian Prime Minister Billy Hughes at the Warwick railway station, Queensland, during his campaign for the 1917 plebiscite on conscription. The egg was thrown by Patrick Michael Brosnan, possibly assisted by his brother Bartie Brosnan.

The Australian Labor Party split of 1916 occurred following severe disagreement within the Australian Labor Party over the issue of proposed World War I conscription in Australia. Labor Prime Minister of Australia Billy Hughes had, by 1916, become an enthusiastic supporter of conscription as a means to boost Australia's contribution to the war effort. On 30 August 1916, he announced plans for a referendum on the issue, and introduced enabling legislation into parliament on 15 September, which passed only with the support of the opposition. Six of Hughes's ministers resigned in protest at the move, and the New South Wales state branch of the Labor Party expelled Hughes. The referendum saw an intense campaign in which Labor figures vehemently advocated on each side of the argument, although the "no" campaign narrowly won on 14 November. In the wake of the referendum defeat, the caucus moved to expel Hughes on 14 November; instead, he and 23 supporters resigned and formed the National Labor Party. Frank Tudor was elected leader of the rump party. Hughes was recommissioned as Prime Minister, heading a minority government supported by the opposition Commonwealth Liberal Party; the two parties then merged as the Nationalist Party of Australia and won the 1917 federal election. The Nationalist Party served as the main conservative party of Australia until 1931, and the split resulted in many early Labor figures ending their careers on the political right. Hughes, for instance, sat as a member of the Nationalists and their successors, the United Australia Party and the Liberal Party, with only a few short breaks until his death in 1952.

During World War I, extensive military recruitment took place in Queensland. Although many enlisted voluntarily, there was considerable pressure for the unwilling to enlist, including two unsuccessful attempts to introduce conscription in 1916 and 1917. Overall, more than 57,700 Queenslanders fought in World War I and over 10,000 of them died.

The Queensland Recruiting Committee was a volunteer organisation in Queensland, Australia, which urged Queensland men to enlist for military service during World War I. It operated from May 1915 to December 1916, when it was replaced by an Australian Government recruitment organisation, the Queensland State Recruiting Committee.

On 9 July 1917, a disturbance broke out at the Brisbane School of Arts, when a meeting of the Women's Compulsory Service Petition League was interrupted by activists from the Women's Peace Army, with the confrontation degenerating into violence and mayhem.

The National Party, known as the United Party from 1923, was a political party in the Australian state of Queensland from 1917 to 1925. Although allied with the federal Nationalist Party, it had different origins in state politics. It sought to combine the state's Liberal Party with the Country Party but the latter soon withdrew. In 1923 the party sought a further unification with the Country Party but only attracted a few recruits. Then in 1925 it merged with the Country Party, initially as the Country Progressive Party with a few members left out and then they were absorbed into the renamed Country and Progressive National Party.