Related Research Articles

The judicial system of Turkey is defined by Articles 138 to 160 of the Constitution of Turkey.

The Constitution of the Republic of Korea is the supreme law of South Korea. It was promulgated on July 17, 1948, and last revised on October 29, 1987.

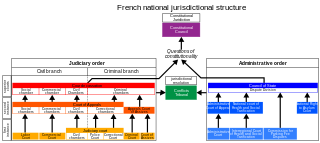

French law has a dual jurisdictional system comprising private law, also known as judicial law, and public law.

The Constitutional Court of Korea is one of the highest courts—along with the Supreme Court—in South Korea's judiciary that exercises constitutional review, seated in Jongno, Seoul. The South Korean Constitution vests judicial power in courts composed of judges, which establishes the ordinary-court system, but also separates an independent constitutional court and grants it exclusive jurisdiction over matters of constitutionality. Specifically, Chapter VI Article 111(1) of the South Korean Constitution specifies the following cases to be exclusively reviewed by the Constitutional Court:

- The constitutionality of a law upon the request of the courts;

- Impeachment;

- Dissolution of a political party;

- Competence disputes between State agencies, between State agencies and local governments, and between local governments; and

- Constitutional complaints as prescribed by [the Constitutional Court] Act.

The Court of Cassation of Belgium is the supreme court of the Belgian judiciary. The court is composed of thirty judges with life tenure who are nominated by the High Council of Justice of Belgium and appointed by the Belgian federal government. The court handles cases in the two main languages of Belgium, Dutch and French, and provides certain facilities for cases in German. The court is assisted in its work by a public prosecutor's office and a bar association, which both function separately from other structures. The duty of the public prosecutor's office is to provide advisory opinions to the court on how the law ought to be interpreted and applied. The attorneys of the court's bar association assist litigants in proceedings before the court; in certain cases, their assistance is mandatory.

The Supreme Court of Korea is the highest ordinary court in the judicial branch of South Korea, seated in Seocho, Seoul. Established under Chapter 5 of the Constitution of South Korea, the Court has ultimate and comprehensive jurisdiction over all cases except those cases falling under the jurisdiction of the Constitutional Court of Korea. It consists of fourteen Justices, including the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of Korea. The Supreme Court is at the top of the hierarchy of all ordinary courts in South Korea, and traditionally represented the conventional judiciary of South Korea. The Supreme Court has equivalent status as one of the two highest courts in South Korea. The other is the Constitutional Court of Korea.

The chief justice of the Supreme Court of Korea is the chief justice of the Supreme Court of Korea. As presiding judge of the grand bench composed of two-thirds of fourteen Supreme Court justices, the chief represents the Supreme Court of Korea. The chief justice is regarded as one of two equivalent heads of judicial branch in Government of South Korea. Another head is the president of the Constitutional Court of Korea. The current chief justice of the Supreme Court of Korea is vacant and Supreme Court Justice Ahn Chul-sang is acting as the chief justice of the Supreme Court of Korea.

In most legal jurisdictions, a supreme court, also known as a court of last resort, apex court, and highcourt of appeal, and court of final appeal, is the highest court within the hierarchy of courts. Broadly speaking, the decisions of a supreme court are binding on all other courts in a nation and are not subject to further review by any other court. Supreme courts typically function primarily as appellate courts, hearing appeals from decisions of lower trial courts, or from intermediate-level appellate courts. A supreme court can also, in certain circumstances, act as a court of original jurisdiction.

The Constitutional Court of Turkey is the highest legal body for constitutional review in Turkey. It "examines the constitutionality, in respect of both form and substance, of laws, decrees having the force of law, and the Rules of Procedure of the Turkish Grand National Assembly". If necessary, it also functions as the Supreme Criminal Court to hear any cases raised about the President, Vice President, members of the Cabinet, or judges of the high courts. In addition to those functions, it examines individual applications on the grounds that one of the fundamental rights and freedoms within the scope of the European Convention on Human Rights which are guaranteed by the Constitution has been violated by public authorities.

The Court of Cassation, officially called the Supreme Court of Appeals of the Republic of Turkey, is the last instance for reviewing verdicts given by courts of criminal and civil justice in Turkey.

The Monegasque Supreme Court is the highest court of law in the city-state of Monaco for judicial appeals, administrative matters as well as ensuring the constitution of Monaco is upheld. It consists of three full judges and two assistant judges, appointed by the Prince of Monaco at the recommendation of the National Council of Monaco, the Crown Council, the Council of State, the Court of First Instance and the Court of Appeal. This is done in the ratio of one judge per institution. The Supreme Court was established in 1962 following the new constitution to guarantee fundamental liberties.

The Supreme Court is the court of last resort in Serbia which reviews and possibly overturns previous rulings made by lower courts.

The judicial system of Syria is a synthesis of Ottoman, French, and Islamic laws. The civil, commercial and criminal codes are primarily based on the French legal practices. Promulgated in 1949, those laws have special provisions sanctioned to limit application of customary law among beduin and religious minorities. The Islamic religious courts continue to function in some parts of the country, but their jurisdiction is limited to issues of personal status, such as marriage, divorce, paternity, custody of children, and inheritance. Nonetheless, in 1955 a personal code pertaining to many aspects of personal status was developed. This law modified and modernized sharia by improving the status of women and clarifying the laws of inheritance.

The judiciary of Italy is composed of courts and public prosecutor offices responsible for the administration of justice in the Italian Republic. These offices are occupied by judges and prosecutors respectively, who are known as magistrates. Magistrates belong to the magistracy, that is to say a branch of the State that may only be accessed by Italian citizens who hold an Italian Juris Doctor and successfully partake in one of the relevant competitive public examinations organised by the Ministry of justice.

The Supreme Court of the Republic of Albania is the highest court of Albania and is the final court of appeals in the country's judicial system. It is composed of seventeen judges: the Chief Justice and sixteen Members.

The judiciary of South Korea is the judicial branch (사법부) of South Korean central government, established by Chapter 5 and 6 of the Constitution of South Korea.

The President of the Constitutional Court of Korea is the Chief Justice of the Constitutional Court of Korea. As presiding judge of Full bench composed of nine Justices, the President represents the Constitutional Court of Korea.

The Association of Asian Constitutional Courts and Equivalent Institutions (AACC) is an association of the constitutional courts and other equivalent institutions in region of Asia, to promote independence and cooperation of constitutional justice in Asian region. The Association is a cooperation group of the Venice Commission for constitutional justice in the Asian region.

Ordinary court or judicial court is a type of court with comprehensive subject-matter jurisdiction compared to 'specialized court' with limited jurisdiction over specific field of matters, such as intellectual property court. Due to its comprehensive feature, ordinary courts usually deal with civil case and criminal case, and treated as core part of conventional judiciary. Especially for common law countries, the term superior court is used for courts with general jurisdiction, compared to courts with limited jurisdiction over minor, petty cases such as small claims court.

An extraordinary court, or special court, is a type of court that is established outside of ordinary judiciary, composed of irregularly selected judges or applies irregular procedure for judgment. Since extraordinary court can be abused to infringe fundamental rights of individuals, contemporaly most of countries ban such courts by constitution or statutes. Usually, modern military courts judged by courts-martial are regarded as examples of extraordinary courts.

References

- ↑ "Jurisdiction and Organization of AACC Members: Constitutional Court, Republic of Korea - Fact files". AACC Secretariat on Research and Development. Retrieved 2022-04-05.

- ↑ "Constitutional Court Act". Korea Legislation Research Institute. Retrieved 2022-04-05.

- ↑ "Classification of Public Officials". Ministry of Personnel Management, South Korea. Retrieved 2022-04-05.

- ↑ "Constitution of the Republic of Korea". Korea Legislation Research Institute. Retrieved 2022-04-05.

- ↑ "Former Justices". Constitutional Court of Korea. Retrieved 2022-04-05.

- ↑ "les magistrats du siege" (in French). Cour de Cassation. Retrieved 2022-04-05.

- ↑ "신임 헌재소장 후보에 유남석 헌법재판관". www.lawtimes.co.kr (in Korean). 29 August 2018. Retrieved 2022-04-05.

- ↑ "Court Organization Act". Korea Legislation Research Institute. Retrieved 2022-04-05.

- ↑ "Rapporteur Judges from the Human Rights Department of the Ministry of Justice complete the HELP online course on Admissibility Criteria". Human Rights Education for Legal Professions, Council of Europe. Retrieved 2022-04-17.

- ↑ "Law on Constitutional Court". The Constitutional Court of the Republic of Turkey. Retrieved 2022-04-05.

- ↑ "Jurisdiction and Organization of AACC Members: Constitutional Court, Turkey - Fact files". AACC Secretariat on Research and Development. Retrieved 2022-04-05.

- ↑ "Rapporteur, The Structure and Duties of the Court". The Constitutional Court of the Republic of Turkey. Retrieved 2022-04-05.

- ↑ "Turkish Constitution, Legislation". The Constitutional Court of the Republic of Turkey. Retrieved 2022-04-05.