In general, a port of entry (POE) is a place where one may lawfully enter a country. It typically has border security staff and facilities to check passports and visas and to inspect luggage to assure that contraband is not imported. International airports are usually ports of entry, as are road and rail crossings on a land border. Seaports can be used as ports of entry only if a dedicated customs presence is posted there. The choice of whether to become a port of entry is up to the civil authority controlling the port.

The United States Border Patrol (USBP) is a federal law enforcement agency under the United States Customs and Border Protection (CBP) and is responsible for securing the borders of the United States. According to its website as of 2022, its mission is to "Protect the American people, safeguard our borders, and enhance the nation’s economic prosperity."

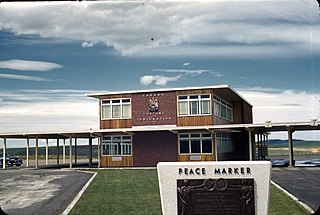

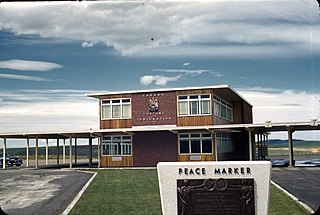

The Canada–United States border is the longest international border in the world. The boundary is 8,891 km (5,525 mi) long. The land border has two sections: Canada's border with the contiguous United States to its south, and with the U.S. state of Alaska to its west. The bi-national International Boundary Commission deals with matters relating to marking and maintaining the boundary, and the International Joint Commission deals with issues concerning boundary waters. The agencies responsible for facilitating legal passage through the international boundary are the Canada Border Services Agency (CBSA) and U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP).

The United States Customs Service was a federal law enforcement agency of the U.S. federal government. Established on July 31, 1789, it collected import tariffs, performed other selected border security duties, as well as conducted criminal investigations.

The Canada Border Services Agency is a federal law enforcement agency that is responsible for border control, immigration enforcement, and customs services in Canada.

United States Customs and Border Protection (CBP) is the largest federal law enforcement agency of the United States Department of Homeland Security. It is the country's primary border control organization, charged with regulating and facilitating international trade, collecting import duties, as well as enforcing U.S. regulations, including trade, customs and immigration. CBP is one of the largest law enforcement agencies in the United States. It has a workforce of more than 45,600 federal agents and officers. It is headquartered in Washington, D.C.

INSPASS, or INS Passenger Accelerated Service System, was a program of the United States Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) during the 1990s and early 2000s the purpose of which was to facilitate the entry of pre-screened low-risk travellers through immigration and customs at certain airports.

United States border preclearance is the United States Department of Homeland Security's (DHS) practice of operating prescreening border control facilities at airports and other ports of departure located outside of the United States pursuant to agreements between the United States and host countries. Travelers are subject to immigration and customs inspections by Customs and Border Protection (CBP) officers before boarding their transportation onward to the United States. Preclearance applies to all passengers regardless of their nationality or purpose of travel. Upon arrival, precleared passengers arrive in the United States as domestic travelers, but may still be subject to re-inspection at the discretion of CBP. This process is intended to streamline border procedures, reduce congestion at American ports of entry, and facilitate travel into airports that otherwise lack immigration and customs processing facilities for commercial flights.

NEXUS is a joint Canada Border Services Agency and U.S. Customs and Border Protection-operated Trusted Traveler and expedited border control program designed for pre-approved, low-risk travelers. Members of the program can avoid waits at border entry points by using reserved lanes at land crossings into Canada and the United States, by using self-serve kiosks at airports in Canada, the US and some international locations, or by phoning border officials for a marine entry. A NEXUS membership card is a valid document under the Western Hemisphere Travel Initiative (WHTI), so it can be used in place of a passport, including by air if flying between the US and Canada. However, carrying a valid passport is still recommended, in the rare event that a flight is diverted to an airport without NEXUS support.

Noyes is an unincorporated community in St. Vincent Township, Kittson County, Minnesota, United States. Located in the extreme northwestern corner of the state on the Canada–United States border, Noyes is the northern terminus of U.S. Highway 75 and site of a former road border crossing. U.S. Customs and Border Protection operates a customs inspection station for the Canadian Pacific and BNSF Railway lines that enter from Canada at Noyes. The community of Emerson, Manitoba, lies adjacent to Noyes on the Canadian side of the border.

The Port Passenger Accelerated Service System (PORTPASS) was a suite of programs of the former U.S. Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS), including:

The Secure Electronic Network for Travelers Rapid Inspection (SENTRI) provides expedited U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) processing, at the U.S.-Mexico border, of pre-approved travelers considered low-risk. Voluntarily applicants must undergo a thorough background check against criminal, customs, immigration, law enforcement, and terrorist databases; a 10-fingerprint law enforcement check; and a personal interview with a CBP Officer. The total enrollment fee is $122.50, and SENTRI status is valid for 5 years.

In the United States, border security includes the protection of ports, airports, and the country's 3,017-mile (4,855 km) land border with Canada and 1,933-mile (3,111 km) border with Mexico.

The Videophone Inspection Program (VIP) is a U.S. Customs and Border Protection program that enables boaters entering the United States from Canada to be inspected face-to-face by a CBP inspector upon arrival at a selected reporting station. The program was designed to facilitate the legal entry of pleasure boats into the United States that had not been issued a Form I-68.

The Pittsburg–Chartierville Border Crossing connects the towns of Chartierville, Quebec, and Pittsburg, New Hampshire. The crossing can be reached by U.S. Route 3 on the American side and by Quebec Route 257 on the Canadian side.

The Limestone–Gillespie Portage Border Crossing is an international border crossing connecting the towns of Limestone, Maine, United States, and Grand-Sault, New Brunswick, Canada. The crossing is reached by Maine State Route 229 on the American side and by New Brunswick Route 375 on the Canadian side. The United States crossing facilities are the original facilities first built for this crossing in 1933, and were listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 2014.

The Pacific Highway Border Crossing connects the city of Blaine, Washington and the city of Surrey, British Columbia on the Canada–US border. Interstate 5/Washington State Route 543 on the American side joins British Columbia Highway 15 on the Canadian side. Since the 1970s, commercial vehicles driving directly between Blaine and Surrey have been required to use this route, one of the five busiest commercial US-Canada border crossings.

The Piegan–Carway Border Crossing connects the towns of Babb, Montana, and Cardston, Alberta, on the Canada–United States border. U.S. Route 89 on the American side joins Alberta Highway 2 on the Canadian side.

The Scobey–Coronach Border Crossing connects the towns of Scobey, Montana and Coronach, Saskatchewan on the Canada–US border. Montana Highway 13 on the American side joins Saskatchewan Highway 36 on the Canadian side. An airport with a grass runway that straddles the border is located on the east side of this crossing.