The respiratory system of the horse is the biological system by which a horse circulates air for the purpose of gaseous exchange.

The respiratory system of the horse is the biological system by which a horse circulates air for the purpose of gaseous exchange.

The respiratory system begins with the nares, commonly known as the nostrils, which can expand greatly during intense exercise. The nostrils have an outer ring made of cartilage (the alar cartilage), which serves to hold them open during inhalation. Additionally, a small pocket within them, called the nasal diverticulum, filters debris with the help of the hairs lining the inner nostril. The nasal cavity contains the nasolacrimal duct, which drains tears from the eyes and out the nose.

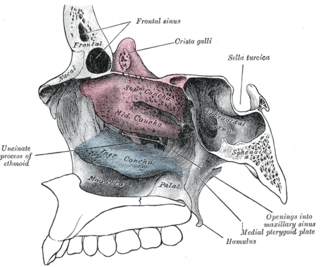

The nasal passages contain two conchae on either side, which help to increase the surface area to which the air is exposed. Additionally, the sinuses within the skull are able to drain through the nasal passage. The nasal passage join to the larynx via the pharynx. The pharynx is about 15 cm (5.9 in) long in an adult, and includes the nasopharynx, which protect the entrance to the auditory tubes, the oropharynx, which contains tonsillar tissue, and the laryngopharynx.

In parallel to the main nasal passages, the horse has a complex system of paranasal sinuses - air filled spaces within the head which communicate with the respiratory tract, and serve to reduce the weight of the head. These consist of:

A flap of tissue called the soft palate blocks off the pharynx from the mouth (oral cavity) of the horse, except when swallowing. This helps to prevent the horse from inhaling food, but does not allow use of the mouth to breathe when in respiratory distress, a horse can only breathe through its nostrils. For this same reason, horses also cannot pant as a method of thermoregulation.

The genus Equus has a unique part of the respiratory system called the guttural pouch, which is thought to equalize air pressure on the tympanic membrane. These (left and right, separated by a narrow septum) is located in "Vyborg's triangle", between the mandibles but below the occiput. With a capacity of 300 to 500 ml, it fills with air when the horse swallows or exhales.

The larynx lies between the pharynx and the trachea, and is made up of 5 pieces of cartilage which serve to open the glottis. The larynx not only allows the horse to vocalize, but also prevents aspiration of food and helps to control the volume of air inhaled. The trachea is the tube which carries air from the oral cavity and into the lungs, and is about 75–80 cm (30–31 in) in length in the adult. It is held permanently open by 50–60 C-shaped rings of cartilage, 5–6 cm (2.0–2.4 in) in diameter. [2]

At the bifurcation of the trachea, there are two bronchi, the right of which is slightly larger in size. The bronchi then branch into smaller bronchioles, which in turn branch off into smaller bronchioles until they reach the alveoli (which absorb oxygen from the air and releases the carbon dioxide waste). The bronchi and bronchioles are all held within the lungs of the horse, which is located in the animal's thoracic cavity. The lung is made up of a spongy, but very stretchy, material which has 2 lobes on the right and left side (a smaller, apical lobe and a large, caudal lobe) in addition to the accessory lobe. Blood is carried into the lungs via the pulmonary artery, where it is oxygenated at the alveoli and then returned to the heart by the pulmonary veins.

The lungs are expanded with the help of the diaphragm, a muscular sheet of tissue which contracts away from the thoracic cavity, thereby decreasing the pressure and pulling air into the lungs. When fully expanded, the lungs can reach to the 16th rib of the horse.

An adult horse has an average rate of respiration at rest of 12 to 24 breaths per minute. [3] Young foals have higher resting respiratory rates than adult horses, usually 36 to 40 breaths per minute. [3] Heat and humidity can raise the respiration rate considerably, especially if the horse has a dark coat and is in the sun. The respiration will often change if the horse becomes excited or distressed, and can therefore be useful in determining the health of the animal.

At the gallop, the horse breathes in rhythm with every stride: [4] as the abdominal muscles pull the hind legs forward in the "suspension phase" of the gallop, the organs within the abdominal cavity are pushed backward from the diaphragm, thereby bringing air into the lungs and causing the horse to inhale. As the neck is lowered during the extended phase of the gallop, the hind legs move backward and the gut contents shift forwards, pushing into the diaphragm and forcing air out of the lungs. [5]

The horse's olfactory receptors are located in the mucosa of the upper nasal cavity. Due to the length of the nasal cavity, there is a large area of these receptors, and the horse has a better ability to smell than a human. Additionally, the horse also has a vomeronasal organ, or Jacobson's Organ, which is in the hard palate, and is able to pick up pheromones and other scents when a horse exhibits the flehmen response. The flehmen response forces air through slits in the nasal cavity and into the vomeronasal organ. Unlike many other animals, the horse's Jacobson's Organ doesn't open into the oral cavity. [6]

The lungs are the primary organs of the respiratory system in many animals, including humans. In mammals and most other tetrapods, two lungs are located near the backbone on either side of the heart. Their function in the respiratory system is to extract oxygen from the atmosphere and transfer it into the bloodstream, and to release carbon dioxide from the bloodstream into the atmosphere, in a process of gas exchange. Respiration is driven by different muscular systems in different species. Mammals, reptiles and birds use their musculoskeletal systems to support and foster breathing. In early tetrapods, air was driven into the lungs by the pharyngeal muscles via buccal pumping, a mechanism still seen in amphibians. In humans, the primary muscle that drives breathing is the diaphragm. The lungs also provide airflow that makes vocalisation including speech possible.

The larynx, commonly called the voice box, is an organ in the top of the neck involved in breathing, producing sound and protecting the trachea against food aspiration. The opening of larynx into pharynx known as the laryngeal inlet is about 4–5 centimeters in diameter. The larynx houses the vocal cords, and manipulates pitch and volume, which is essential for phonation. It is situated just below where the tract of the pharynx splits into the trachea and the esophagus. The word 'larynx' comes from the Ancient Greek word lárunx ʻlarynx, gullet, throatʼ.

The respiratory system is a biological system consisting of specific organs and structures used for gas exchange in animals and plants. The anatomy and physiology that make this happen varies greatly, depending on the size of the organism, the environment in which it lives and its evolutionary history. In land animals, the respiratory surface is internalized as linings of the lungs. Gas exchange in the lungs occurs in millions of small air sacs; in mammals and reptiles, these are called alveoli, and in birds, they are known as atria. These microscopic air sacs have a very rich blood supply, thus bringing the air into close contact with the blood. These air sacs communicate with the external environment via a system of airways, or hollow tubes, of which the largest is the trachea, which branches in the middle of the chest into the two main bronchi. These enter the lungs where they branch into progressively narrower secondary and tertiary bronchi that branch into numerous smaller tubes, the bronchioles. In birds, the bronchioles are termed parabronchi. It is the bronchioles, or parabronchi that generally open into the microscopic alveoli in mammals and atria in birds. Air has to be pumped from the environment into the alveoli or atria by the process of breathing which involves the muscles of respiration.

The trachea, also known as the windpipe, is a cartilaginous tube that connects the larynx to the bronchi of the lungs, allowing the passage of air, and so is present in almost all animals lungs. The trachea extends from the larynx and branches into the two primary bronchi. At the top of the trachea, the cricoid cartilage attaches it to the larynx. The trachea is formed by a number of horseshoe-shaped rings, joined together vertically by overlying ligaments, and by the trachealis muscle at their ends. The epiglottis closes the opening to the larynx during swallowing.

The respiratory tract is the subdivision of the respiratory system involved with the process of conducting air to the alveoli for the purposes of gas exchange in mammals. The respiratory tract is lined with respiratory epithelium as respiratory mucosa.

A bronchus is a passage or airway in the lower respiratory tract that conducts air into the lungs. The first or primary bronchi to branch from the trachea at the carina are the right main bronchus and the left main bronchus. These are the widest bronchi, and enter the right lung, and the left lung at each hilum. The main bronchi branch into narrower secondary bronchi or lobar bronchi, and these branch into narrower tertiary bronchi or segmental bronchi. Further divisions of the segmental bronchi are known as 4th order, 5th order, and 6th order segmental bronchi, or grouped together as subsegmental bronchi. The bronchi, when too narrow to be supported by cartilage, are known as bronchioles. No gas exchange takes place in the bronchi.

The bronchioles are the smaller branches of the bronchial airways in the lower respiratory tract. They include the terminal bronchioles, and finally the respiratory bronchioles that mark the start of the respiratory zone delivering air to the gas exchanging units of the alveoli. The bronchioles no longer contain the cartilage that is found in the bronchi, or glands in their submucosa.

The nasal cavity is a large, air-filled space above and behind the nose in the middle of the face. The nasal septum divides the cavity into two cavities, also known as fossae. Each cavity is the continuation of one of the two nostrils. The nasal cavity is the uppermost part of the respiratory system and provides the nasal passage for inhaled air from the nostrils to the nasopharynx and rest of the respiratory tract.

In anatomy, a nasal concha, also called a nasal turbinate or turbinal, is a long, narrow, curled shelf of bone that protrudes into the breathing passage of the nose in humans and various other animals. The conchae are shaped like an elongated seashell, which gave them their name. A concha is any of the scrolled spongy bones of the nasal passages in vertebrates.

The cough reflex occurs when stimulation of cough receptors in the respiratory tract by dust or other foreign particles produces a cough, which causes rapidly moving air which usually remove the foreign material before it reaches the lungs. This typically clears particles from the bronchi and trachea, the tubes that feed air to lung tissue from the nose and mouth. The larynx and carina are especially sensitive. Cough receptors in the surface cells (epithelium) of the respiratory tract are also sensitive to chemicals. Terminal bronchioles and even the alveoli are sensitive to chemicals such as sulfur dioxide gas or chlorine gas.

The human nose is the first organ of the respiratory system. It is also the principal organ in the olfactory system. The shape of the nose is determined by the nasal bones and the nasal cartilages, including the nasal septum, which separates the nostrils and divides the nasal cavity into two.

A sinus is a sac or cavity in any organ or tissue, or an abnormal cavity or passage. In common usage, "sinus" usually refers to the paranasal sinuses, which are air cavities in the cranial bones, especially those near the nose and connecting to it. Most individuals have four paired cavities located in the cranial bone or skull.

The muscles of respiration are the muscles that contribute to inhalation and exhalation, by aiding in the expansion and contraction of the thoracic cavity. The diaphragm and, to a lesser extent, the intercostal muscles drive respiration during quiet breathing. The elasticity of these muscles is crucial to the health of the respiratory system and to maximize its functional capabilities.

A nose is a sensory organ and respiratory structure in vertebrates. It consists of a nasal cavity inside the head, and an external nose on the face. The external nose houses the nostrils, or nares, a pair of tubes providing airflow through the nose for respiration. Where the nostrils pass through the nasal cavity they widen, are known as nasal fossae, and contain turbinates and olfactory mucosa. The nasal cavity also connects to the paranasal sinuses. From the nasal cavity, the nostrils continue into the pharynx, a switch track valve connecting the respiratory and digestive systems.

The Frenzel Maneuver is named after Hermann Frenzel. The maneuver was developed in 1938 and originally was taught to dive bomber pilots during World War II. The maneuver is used to equalize pressure in the middle ear. Today, the maneuver is also performed by scuba divers, free divers and by passengers on aircraft as they descend.

Breathing is the rhythmical process of moving air into (inhalation) and out of (exhalation) the lungs to facilitate gas exchange with the internal environment, mostly to flush out carbon dioxide and bring in oxygen.

The pharynx is the part of the throat behind the mouth and nasal cavity, and above the esophagus and trachea. It is found in vertebrates and invertebrates, though its structure varies across species. The pharynx carries food to the esophagus and air to the larynx. The flap of cartilage called the epiglottis stops food from entering the larynx.

A breathing tube is a hollow component that can serve as a conduit for breathing. Various types of breathing tubes are available for different specific applications. Many of them are generally known by more specific terms.

Development of the respiratory system begins early in the fetus. It is a complex process that includes many structures, most of which arise from the endoderm. Towards the end of development, the fetus can be observed making breathing movements. Until birth, however, the mother provides all of the oxygen to the fetus as well as removes all of the fetal carbon dioxide via the placenta.