Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra was a Spanish writer widely regarded as the greatest writer in the Spanish language and one of the world's pre-eminent novelists. He is best known for his novel Don Quixote, a work considered as the first modern novel. The novel has been labelled by many well-known authors as the "best book of all time" and the "best and most central work in world literature".

The picaresque novel is a genre of prose fiction. It depicts the adventures of a roguish but "appealing hero", usually of low social class, who lives by his wits in a corrupt society. Picaresque novels typically adopt the form of "an episodic prose narrative" with a realistic style. There are often some elements of comedy and satire. Although the term "picaresque novel" was coined in 1810, the picaresque genre began with the Spanish novel Lazarillo de Tormes (1554), which was published anonymously during the Spanish Golden Age because of its anticlerical content. Literary works from Imperial Rome published during the 1st–2nd century AD, such as Satyricon by Petronius and The Golden Ass by Apuleius had a relevant influence on the picaresque genre and are considered predecessors. Other notable early Spanish contributors to the genre included Mateo Alemán's Guzmán de Alfarache (1599–1604) and Francisco de Quevedo's El Buscón (1626). Some other ancient influences of the picaresque genre include Roman playwrights such as Plautus and Terence. The Golden Ass by Apuleius nevertheless remains, according to different scholars such as F. W. Chandler, A. Marasso, T. Somerville and T. Bodenmüller, the primary antecedent influence for the picaresque genre. Subsequently, following the example of Spanish writers, the genre flourished throughout Europe for more than 200 years and it continues to have an influence on modern literature and fiction.

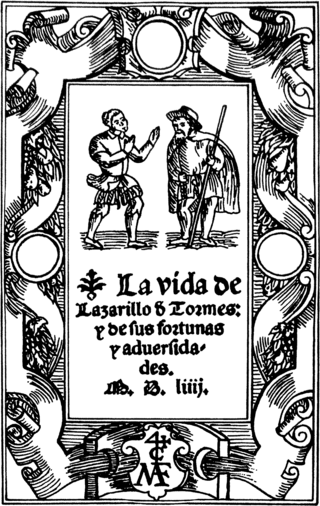

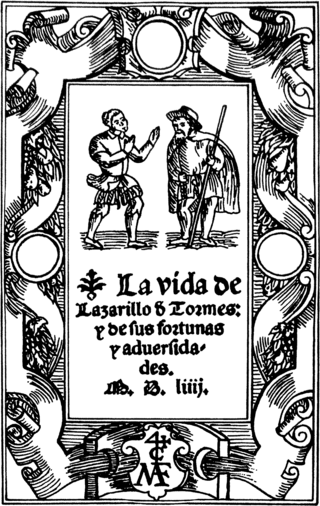

The Life of Lazarillo de Tormes and of His Fortunes and Adversities is a Spanish novella, published anonymously because of its anticlerical content. It was published simultaneously in three cities in 1554: Alcalá de Henares, Burgos and Antwerp. The Alcalá de Henares edition adds some episodes which were most likely written by a second author. It is most famous as the book establishing the style of the picaresque satirical novel.

Germanía is the Spanish term for the argot used by criminals or in jails in Spain during 16th and 17th centuries. Its purpose is to keep outsiders out of the conversation. The ultimate origin of the word is the Latin word germanus, through Catalan germà (brother) and germania.

Lankhmar is a fictional city in the Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser stories by Fritz Leiber. It is situated on the world of Nehwon, just west of the Great Salt Marsh and east of the River Hlal, and serves as the home of Leiber's two antiheroes.

La Galatea was Miguel de Cervantes’ first book, published in 1585. Under the guise of pastoral characters, it is an examination of love and contains many allusions to contemporary literary figures. It enjoyed modest success, but was not soon reprinted; its promised sequel was never published.

Juan Martínez de Jáuregui y Aguilar was a Spanish poet, scholar and painter in the Siglo de Oro.

The Garduña is a mythical organized, secret criminal society said to have been founded in Spain in the late Middle Ages. It was said to have been a prison gang that grew into a more organized entity over time, involved with robbery, kidnapping, arson, and murder-for-hire. Its statutes were said to have been approved in Toledo in 1420 after being founded around 1417.

An hidalgo or a fidalgo is a member of the Spanish or Portuguese nobility; the feminine forms of the terms are hidalga, in Spanish, and fidalga, in Portuguese and Galician. Legally, an hidalgo is a nobleman by blood who can pass his noble condition to his children, as opposed to someone who acquired his nobility by royal grace. In practice, hidalgos enjoyed important privileges, such as being exempt from paying taxes, having the right to bear arms, having a coat of arms, having a separate legal and court system whereby they could only be judged by their peers, not being subject to the death sentence unless it was authorized by the king, etc.

In popular fiction, a thieves' guild is a formal association of criminals who participate in theft-related organized crime. The trope has been explored in literature, cinema, comic books, and gaming, such as in the Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser story "Thieves' House" by Fritz Leiber and the role-playing game Dungeons & Dragons. Though these more modern works are fictitious, the concept is inspired by real-world examples from history, such as Jonathan Wild and his gang of thieves.

Cide Hamete Benengeli is a fictional Arab Muslim historian created by Miguel de Cervantes in his novel Don Quixote, who Cervantes says is the true author of most of the work. This is a skilful metafictional literary pirouette that seems to give more credibility to the text, making the reader believe that Don Quixote was a real person and the story is decades old. However, it is obvious to the reader that such a thing is impossible, and that the pretense of Cide Hamete's work is meant as a joke.

"El licenciado Vidriera" is a short story written by Miguel de Cervantes and included in his Novelas ejemplares, first published in 1613. In the story, a young scholar goes mad, believing himself to be made entirely of glass, and becomes famous for his satirical comments on the society around him. He eventually becomes cured and leaves his scholar's life to join the army, dying in battle.

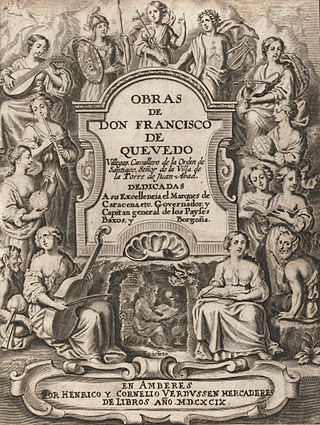

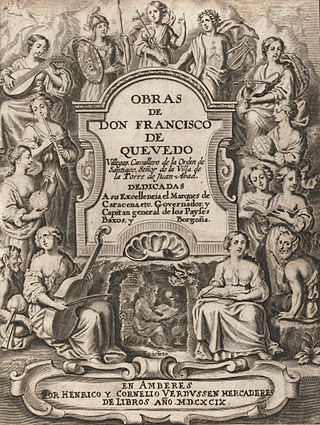

Spanish Baroque literature is the literature written in Spain during the Baroque, which occurred during the 17th century in which prose writers such as Baltasar Gracián and Francisco de Quevedo, playwrights such as Lope de Vega, Tirso de Molina, Calderón de la Barca and Juan Ruiz de Alarcón, or the poetic production of the aforementioned Francisco de Quevedo, Lope de Vega and Luis de Góngora reached their zenith. Spanish Baroque literature is a period of writing which begins approximately with the first works of Luis de Góngora and Lope de Vega, in the 1580s, and continues into the late 17th century.

El Buscón is a picaresque novel by Francisco de Quevedo. It was written around 1604 and published in 1626 by a press in Zaragoza, though it had circulated in manuscript form previous to that.

Novelas ejemplares is a series of twelve novellas that follow the model established in Italy. The series was written by Miguel de Cervantes between 1590 and 1612 and printed in Madrid in 1613 by Juan de la Cuesta. Novelas ejemplares followed the publication of the first part of Don Quixote. The novellas were well received.

La gitanilla is the first novella contained in Miguel de Cervantes' collection of short stories, the Novelas ejemplares.

The Curious Impertinent is a 1953 Spanish historical film directed by Flavio Calzavara and starring Aurora Bautista, José María Seoane and Roberto Rey. It is based on a noteworthy story from Don Quixote by Miguel de Cervantes, extracted from his famous exemplary novels.

"The Dialogue of the Dogs" is a novella originating from the fantasy world of Alférez Campuzano, a character from a short story, The Deceitful Marriage. Both are written by author Miguel de Cervantes. It was originally published in a 1613 collection of novellas called Novelas ejemplares.

Gachupín is a Spanish-language term derived from a noble surname of northern Spain, the Cachopín of Laredo. It was popularized during the Spanish Golden Age as a stereotype and literary stock character representing the hidalgo class which was characterized as arrogant and overbearing. It may also be spelled cachopín, guachapín, chaupín or cachupino. The term remained popular in Mexico, where it would come to be used in the Cry of Dolores.

Francisco Rodríguez Marín was a Spanish poet, paremiologist, and lexicologist.