Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra was an Early Modern Spanish writer widely regarded as the greatest writer in the Spanish language and one of the world's pre-eminent novelists. He is best known for his novel Don Quixote, a work considered as the first modern novel. The novel has been labelled by many well-known authors as the "best book of all time" and the "best and most central work in world literature".

This article concerns the period 139 BC – 130 BC.

Marcus Annaeus Lucanus, better known in English as Lucan, was a Roman poet, born in Corduba, Hispania Baetica. He is regarded as one of the outstanding figures of the Imperial Latin period, known in particular for his epic Pharsalia. His youth and speed of composition set him apart from other poets.

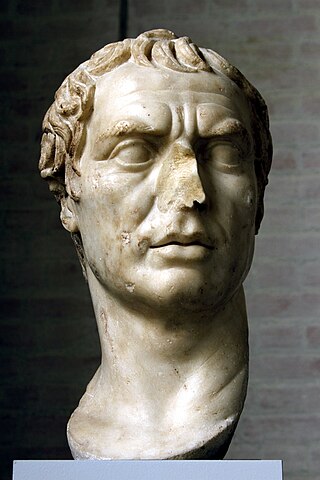

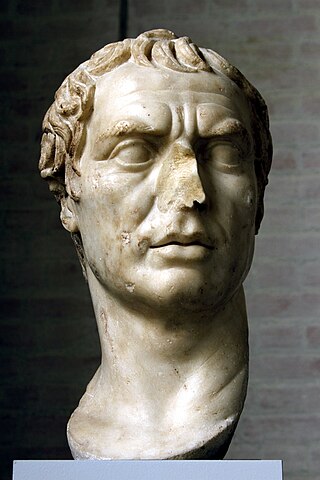

Publius Cornelius Scipio Africanus Aemilianus, known as Scipio Aemilianus or Scipio Africanus the Younger, was a Roman general and statesman noted for his military exploits in the Third Punic War against Carthage and during the Numantine War in Spain. He oversaw the final defeat and destruction of the city of Carthage. He was a prominent patron of writers and philosophers, the most famous of whom was the Greek historian Polybius. In politics, he opposed the populist reform program of his murdered brother-in-law, Tiberius Gracchus.

The Celtiberians were a group of Celts and Celticized peoples inhabiting an area in the central-northeastern Iberian Peninsula during the final centuries BC. They were explicitly mentioned as being Celts by several classic authors. These tribes spoke the Celtiberian language and wrote it by adapting the Iberian alphabet, in the form of the Celtiberian script. The numerous inscriptions that have been discovered, some of them extensive, have enabled scholars to classify the Celtiberian language as a Celtic language, one of the Hispano-Celtic languages that were spoken in pre-Roman and early Roman Iberia. Archaeologically, many elements link Celtiberians with Celts in Central Europe, but also show large differences with both the Hallstatt culture and La Tène culture.

Spanish literature generally refers to literature written in the Spanish language within the territory that presently constitutes the Kingdom of Spain. Its development coincides and frequently intersects with that of other literary traditions from regions within the same territory, particularly Catalan literature, Galician intersects as well with Latin, Jewish, and Arabic literary traditions of the Iberian Peninsula. The literature of Spanish America is an important branch of Spanish literature, with its own particular characteristics dating back to the earliest years of Spain’s conquest of the Americas.

Soria is a municipality and a Spanish city, located on the Douro river in the east of the autonomous community of Castile and León and capital of the province of Soria. Its population is 38,881, 43.7% of the provincial population. The municipality has a surface area of 271,77 km2, with a density of 144.97 inhabitants/km2. Situated at about 1065 metres above sea level, Soria is the second highest provincial capital in Spain.

Numantia is an ancient Celtiberian settlement, whose remains are located on a hill known as Cerro de la Muela in the current municipality of Garray (Soria), Spain.

De Bello Civili, more commonly referred to as the Pharsalia, is a Roman epic poem written by the poet Lucan, detailing the civil war between Julius Caesar and the forces of the Roman Senate led by Pompey the Great. The poem's title is a reference to the Battle of Pharsalus, which occurred in 48 BC, near Pharsalus, Thessaly, in Northern Greece. Caesar decisively defeated Pompey in this battle, which occupies all of the epic's seventh book. In the early twentieth century, translator J. D. Duff, while arguing that "no reasonable judgment can rank Lucan among the world's great epic poets", notes that the work is notable for Lucan's decision to eschew divine intervention and downplay supernatural occurrences in the events of the story. Scholarly estimation of Lucan's poem and poetry has since changed, as explained by commentator Philip Hardie in 2013: "In recent decades, it has undergone a thorough critical re-evaluation, to re-emerge as a major expression of Neronian politics and aesthetics, a poem whose studied artifice enacts a complex relationship between poetic fantasy and historical reality."

The Roman Republic conquered and occupied territories in the Iberian Peninsula that were previously under the control of native Celtic, Iberian, Celtiberian and Aquitanian tribes and the Carthaginian Empire. The Carthaginian territories in the south and east of the peninsula were conquered in 206 BC during the Second Punic War. Control was gradually extended over most of the peninsula without annexations. It was completed after the end of the Roman Republic, by Augustus, the first Roman emperor, who annexed the whole of the peninsula to the Roman Empire in 19 BC.

Antonio Buero Vallejo was a Spanish playwright associated with the Generation of '36 movement and considered the most important Spanish dramatist of the Spanish Civil War.

Lucentum, called Lucentia by Pomponius Mela, is the Roman predecessor of the city of Alicante, Spain. Particularly, it refers to the archaeological site in which the remains of this ancient settlement lie, at a place known as El Tossal de Manises, in the neighborhood of Albufereta.

The Celtiberian oppidum of Numantia was attacked more than once by Roman forces, but the siege of Numantia refers to the culminating and pacifying action of the long-running Numantine War between the forces of the Roman Republic and those of the native population of Hispania Citerior. The Numantine War was the third of the Celtiberian Wars and it broke out in 143 BC. A decade later, in 133 BC, the Roman general and hero of the Third Punic War, Scipio Aemilianus Africanus, subjugated Numantia, the chief Celtiberian city.

Martí de Riquer i Morera, 8th Count of Casa Dávalos was a Spanish literary historian and Romance philologist, a recognised international authority in the field. His writing career lasted from 1934 to 2004. He was also a nobleman and Grandee of Spain.

In ancient Rome the Latin word adlocutio means an address given by a general, usually the emperor, to his massed army and legions, and a general form of Roman salute from the army to their leader. The research of adlocutio focuses on the art of statuary and coinage aspects. It is often portrayed in sculpture, either simply as a single, life-size contrapposto figure of the general with his arm outstretched, or a relief scene of the general on a podium addressing the army. Such relief scenes also frequently appear on imperial coinage.

Toutatis or Teutates is a Celtic god who was worshipped primarily in ancient Gaul and Britain. His name means "god of the tribe", and he has been widely interpreted as a tribal protector. According to Roman writer Lucan, the Gauls offered human sacrifices to him.

Frederick A. de Armas is a literary scholar, critic and novelist who is Robert O. Anderson Distinguished Service Professor in Humanities at the University of Chicago.

Publius Cornelius Scipio Africanus was a Roman general and statesman, most notable as one of the main architects of Rome's victory against Carthage in the Second Punic War. Often regarded as one of the greatest military commanders and strategists of all time, his greatest military achievement was the defeat of Hannibal at the Battle of Zama in 202 BC. This victory in Africa earned him the honorific epithet Africanus, literally meaning 'the African', but meant to be understood as a conqueror of Africa.

James Young Gibson was an essayist and translator noted for his work helping Alexander James Duffield translate Don Quixote into English in 1881, and on his own translations of Journey to Parnassus in 1883, Numantia in 1885 and El Cid in 1887.

"The Dialogue of the Dogs" is a novella originating from the fantasy world of Alférez Campuzano, a character from a short story, The Deceitful Marriage. Both are written by author Miguel de Cervantes. It was originally published in a 1613 collection of novellas called Novelas ejemplares.