Manuel de Falla y Matheu was a Spanish composer and pianist. Along with Isaac Albéniz, Francisco Tárrega, and Enrique Granados, he was one of Spain's most important musicians of the first half of the 20th century. He has a claim to being Spain's greatest composer of the 20th century, although the number of pieces he composed was relatively modest.

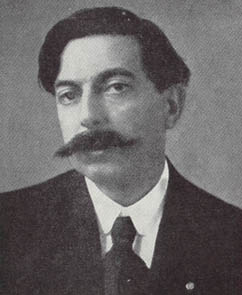

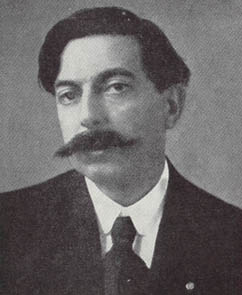

Pantaleón Enrique Joaquín Granados Campiña, commonly known as Enrique Granados in Spanish or Enric Granados in Catalan, was a Spanish composer of classical music, and concert pianist from Catalonia, Spain. His most well-known works include Goyescas, the Spanish Dances, and María del Carmen.

Mario Lavista was a Mexican composer, writer and intellectual.

Luis de Pablo Costales was a Spanish composer belonging to the generation that Cristóbal Halffter named the Generación del 51. Mostly self-taught as a composer and influenced by Maurice Ohana and Max Deutsch, he co-founded ensembles for contemporary music, and organised concert series for it in Madrid. He published translations of notable texts about composers of the Second Viennese School, such as Hans Heinz Stuckenschmidt's biography of Arnold Schoenberg and the publications of Anton Webern. He wrote music in many genres, including film scores such as Erice's The Spirit of the Beehive, and operas including La señorita Cristina. He taught composition not only in Spain, but also in the U.S. and Canada. Among his awards is the Premio Nacional de Música.

Cristóbal Halffter Jiménez-Encina was a Spanish classical composer. He was the nephew of two other composers, Rodolfo and Ernesto Halffter, and is regarded as the most important Spanish composer of the generation of composers designated the Generación del 51.

Julián Orbónde Soto (August 7, 1925, Avilés, Spain – May 21, 1991, Miami, Florida was a Cuban composer who lived and composed in Spain, Cuba, Mexico, and the United States of America. Aaron Copland referred to Orbón as "Cuba's most gifted composer of the new generation."

Carlos Prieto is a Mexican cellist and writer, born in Mexico City. He has received enthusiastic public acclaim and won excellent reviews for his performances throughout the United States, Europe, Russia and the former Soviet Union, Asia, and Latin America. The New York Times review of his Carnegie Hall debut raved, "Prieto knows no technical limitations and his musical instincts are impeccable."

Juan Antonio Orrego-Salas was a Chilean composer, musicologist, music critic, and academic.

The Group of Eight was a group of Spanish composers and musicologists, including Jesús Bal y Gay, Ernesto Halffter and his brother Rodolfo, Juan José Mantecón, Julián Bautista, Fernando Remacha, Rosa García Ascot, Salvador Bacarisse and Gustavo Pittaluga. The group, loosely modelled on Les Six and The Five, was formed in 1930 to oppose musical conservatism in Spain. Its members, who were closely allied to the literary movement Generation of '27, met in Madrid's Residencia de Estudiantes to perform avant-garde works and discuss the aesthetics of music. The group came to an end with the Spanish Civil War and the ensuing Francoist State when most of its members left Madrid or went into exile abroad.

Ernesto Halffter Escriche was a Spanish composer and conductor. He was the brother of Rodolfo Halffter and part of the Grupo de los Ocho, which formed a sub-set of the Generation of '27.

Otto Mayer-Serra, was a Spanish-Mexican musicologist known for being one of the first musicologist to write a systematic study of 20th century Mexican music.

Rosa García Ascot was a Spanish composer and pianist. She was the only woman in the famed Group of Eight, whose members also included Julián Bautista, Ernesto Halffter and his brother Rodolfo, Juan José Mantecón, Fernando Remacha, Salvador Bacarisse and Jesús Bal y Gay. She married Bal y Gay in 1933. Her more notable compositions include Suite para orquesta , Preludio (Prelude), and the Concierto para piano y orquesta .

Alicia Urreta was a Mexican pianist, music educator, and composer.

Janitzio is a symphonic poem by the Mexican composer Silvestre Revueltas, composed in 1933 and revised in 1936. A performance lasts about 15 minutes. The work is a portrait of Janitzio Island in Lake Pátzcuaro, Mexico.

José Antonio Cubiles Ramos was a noted Spanish pianist, conductor and teacher.

Adolfo Odnoposoff was an Argentine-born-and-raised cellist of Russian ancestry who performed in concerts for 5 decades in South, Central, and North America, the Caribbean, Europe, Israel, and the former USSR. He had performed as principal cellist in the Israel Philharmonic and many of the important orchestras of Latin America. He had soloed with major orchestras under conductors that include Arturo Toscanini, Erich Kleiber, Fritz Busch, Juan José Castro, Rafael Kubelik, Victor Tevah, Luis Herrera de la Fuente, Carlos Chavez, Paul Kletzki, Luis Ximénez Caballero (es), Willem van Otterloo, Sir John Barbirolli, Eduardo Mata, Antal Doráti, Jorge Sarmientos (es), Erich Kleiber, George Singer (1908–1980), Ricardo del Carmen (1937-2003), Anshel Brusilow, Pau Casals and Enrique Gimeno. He also performed a Khachaturian work under the direction of Khachaturian.

Música de feria is a composition for string quartet by the Mexican composer and violinist Silvestre Revueltas, written in 1932. Though not so titled by the composer, it is sometimes referred to as his String Quartet No. 4. A performance lasts a little more than nine minutes.

Adolfo Salazar Ruiz de Palacios was a Spanish music historian, music critic, composer, and diplomat of the first half of the twentieth century. He was the preeminent Spanish musicologist of the Silver Age. Fluent in Spanish, French, and English, he was an intellectual and expert of the artistic and cultural currents of his time, and a brilliant polemicist. He maintained a close connection with other prominent Spanish intellectuals and musicians including José Ortega y Gasset, Jesús Bal y Gay, and Ernesto Halffter. In his writings, he was a defender of the French musical aesthetic of Maurice Ravel and Claude Debussy.

Maria Teresa Naranjo Ochoa was a Mexican virtuoso pianist and teacher.

The National Prize for Musical Arts was created in Chile in 1992 under Law 19169 as one of the replacements of the National Prize of Art. It is granted "to the person who has distinguished himself by his achievements in the respective area of the arts". It is part of the National Prize of Chile.