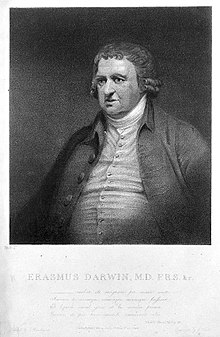

Erasmus Robert Darwin was an English physician. One of the key thinkers of the Midlands Enlightenment, he was also a natural philosopher, physiologist, slave-trade abolitionist, inventor, freemason, and poet.

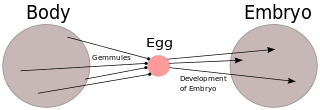

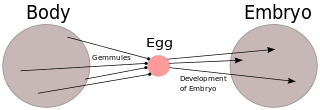

Pangenesis was Charles Darwin's hypothetical mechanism for heredity, in which he proposed that each part of the body continually emitted its own type of small organic particles called gemmules that aggregated in the gonads, contributing heritable information to the gametes. He presented this 'provisional hypothesis' in his 1868 work The Variation of Animals and Plants Under Domestication, intending it to fill what he perceived as a major gap in evolutionary theory at the time. The etymology of the word comes from the Greek words pan and genesis ("birth") or genos ("origin"). Pangenesis mirrored ideas originally formulated by Hippocrates and other pre-Darwinian scientists, but using new concepts such as cell theory, explaining cell development as beginning with gemmules which were specified to be necessary for the occurrence of new growths in an organism, both in initial development and regeneration. It also accounted for regeneration and the Lamarckian concept of the inheritance of acquired characteristics, as a body part altered by the environment would produce altered gemmules. This made Pangenesis popular among the neo-Lamarckian school of evolutionary thought. This hypothesis was made effectively obsolete after the 1900 rediscovery among biologists of Gregor Mendel's theory of the particulate nature of inheritance.

Lamarckism, also known as Lamarckian inheritance or neo-Lamarckism, is the notion that an organism can pass on to its offspring physical characteristics that the parent organism acquired through use or disuse during its lifetime. It is also called the inheritance of acquired characteristics or more recently soft inheritance. The idea is named after the French zoologist Jean-Baptiste Lamarck (1744–1829), who incorporated the classical era theory of soft inheritance into his theory of evolution as a supplement to his concept of orthogenesis, a drive towards complexity.

The history of zoology before Charles Darwin's 1859 theory of evolution traces the organized study of the animal kingdom from ancient to modern times. Although the concept of zoology as a single coherent field arose much later, systematic study of zoology is seen in the works of Aristotle and Galen in the ancient Greco-Roman world. This work was developed in the Middle Ages by Islamic medicine and scholarship, and in turn their work was extended by European scholars such as Albertus Magnus.

This is a list of topics in evolutionary biology.

Robert Edmond Grant MD FRCPEd FRS FRSE FZS FGS was a British anatomist and zoologist.

The Transmutation of species and transformism are 18th and early 19th-century ideas about the change of one species into another that preceded Charles Darwin's theory of evolution through natural selection. The French Transformisme was a term used by Jean Baptiste Lamarck in 1809 for his theory, and other 18th and 19th century proponents of pre-Darwinian evolutionary ideas included Denis Diderot, Étienne Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire, Erasmus Darwin, Robert Grant, and Robert Chambers, the anonymous author of the book Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation. Such ideas were associated with 18th century ideas of Deism and human progress. Opposition in the scientific community to these early theories of evolution, led by influential scientists like the anatomists Georges Cuvier and Richard Owen, and the geologist Charles Lyell, was intense. The debate over them was an important stage in the history of evolutionary thought and influenced the subsequent reaction to Darwin's theory.

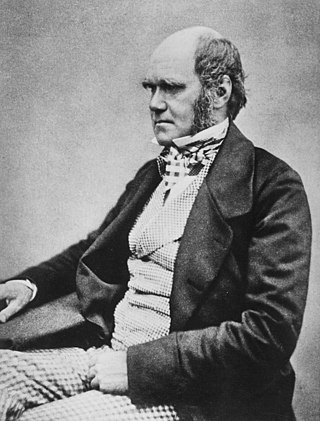

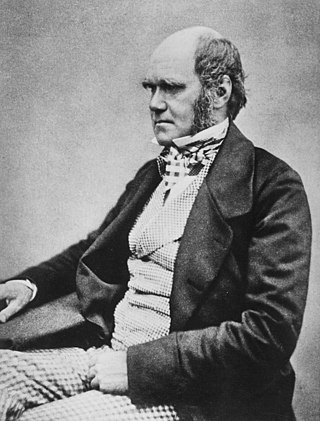

The inception of Darwin's theory occurred during an intensively busy period which began when Charles Darwin returned from the survey voyage of the Beagle, with his reputation as a fossil collector and geologist already established. He was given an allowance from his father to become a gentleman naturalist rather than a clergyman, and his first tasks were to find suitable experts to describe his collections, write out his Journal and Remarks, and present papers on his findings to the Geological Society of London.

Charles Darwin's education gave him a foundation in the doctrine of Creation prevalent throughout the Western world at the time, as well as knowledge of medicine and theology. More significantly, it led to his interest in natural history, which culminated in his taking part in the second voyage of HMS Beagle and the eventual inception of his theory of natural selection. Although Darwin changed his field of interest several times in these formative years, many of his later discoveries and beliefs were foreshadowed by the influences he had as a youth.

Zoonomia; or the Laws of Organic Life (1794–96) is a two-volume medical work by Erasmus Darwin dealing with pathology, anatomy, psychology, and the functioning of the body. Its primary framework is one of associationist psychophysiology. The book is now best remembered for its early ideas relating to the theory of evolution, specifically forms of developmentalism similar to Lamarckism. However, despite Erasmus Darwin's familial connection as grandfather to Charles Darwin, the proto-evolutionary ideas in Zoonomia did not have a lasting influence.

Emma Nora Barlow, Lady Barlow, was a British botanist and geneticist. The granddaughter of the British naturalist Charles Darwin, Barlow began her academic career studying botany at Cambridge under Frederick Blackman, and continued her studies in the new field of genetics under William Bateson from 1904 to 1906. Her primary research focus when working with Bateson was the phenomenon of herostylism within the primrose family. In later life she was one of the first Darwinian scholars, and founder of the Darwin Industry of scholarly research into her grandfather's life and discoveries. She lived to 103.

Charles Robert Darwin was an English naturalist, geologist, and biologist, widely known for his contributions to evolutionary biology. His proposition that all species of life have descended from a common ancestor is now generally accepted and considered a fundamental scientific concept. In a joint publication with Alfred Russel Wallace, he introduced his scientific theory that this branching pattern of evolution resulted from a process he called natural selection, in which the struggle for existence has a similar effect to the artificial selection involved in selective breeding. Darwin has been described as one of the most influential figures in human history and was honoured by burial in Westminster Abbey.

Humboldtian science refers to a movement in science in the 19th century closely connected to the work and writings of German scientist, naturalist, and explorer Alexander von Humboldt. It maintained a certain ethics of precision and observation, which combined scientific field work with the sensitivity and aesthetic ideals of the age of Romanticism. Like Romanticism in science, it was rather popular in the 19th century. The term was coined by Susan Faye Cannon in 1978. The example of Humboldt's life and his writings allowed him to reach out beyond the academic community with his natural history and address a wider audience with popular science aspects. It has supplanted the older Baconian method, related as well to a single person, Francis Bacon.

19th-century science was greatly influenced by Romanticism, an intellectual movement that originated in Western Europe as a counter-movement to the late-18th-century Enlightenment. Romanticism incorporated many fields of study, including politics, the arts, and the humanities.

The Darwin Industry refers to historical scholarship about, and the large community of historians of science working on, Charles Darwin's life, work, and influence. The term "has a slightly derogatory connotation, as if the scale of the research has gotten out of control with people cranking out studies on perhaps less and less important aspects of Darwin's work"; but it was originally a self-designation of the scholars who began re-evaluating Darwin and studying his manuscripts and correspondence in the second half of the 20th century.

Evolutionary ideas during the periods of the Renaissance and the Enlightenment developed over a time when natural history became more sophisticated during the 17th and 18th centuries, and as the scientific revolution and the rise of mechanical philosophy encouraged viewing the natural world as a machine with workings capable of analysis. But the evolutionary ideas of the early 18th century were of a religious and spiritural nature. In the second half of the 18th century more materialistic and explicit ideas about biological evolution began to emerge, adding further strands in the history of evolutionary thought.

Julian Huxley used the phrase "the eclipse of Darwinism" to describe the state of affairs prior to what he called the "modern synthesis". During the "eclipse", evolution was widely accepted in scientific circles but relatively few biologists believed that natural selection was its primary mechanism. Historians of science such as Peter J. Bowler have used the same phrase as a label for the period within the history of evolutionary thought from the 1880s to around 1920, when alternatives to natural selection were developed and explored—as many biologists considered natural selection to have been a wrong guess on Charles Darwin's part, or at least to be of relatively minor importance.

Evolutionary thought, the recognition that species change over time and the perceived understanding of how such processes work, has roots in antiquity—in the ideas of the ancient Greeks, Romans, Chinese, Church Fathers as well as in medieval Islamic science. With the beginnings of modern biological taxonomy in the late 17th century, two opposed ideas influenced Western biological thinking: essentialism, the belief that every species has essential characteristics that are unalterable, a concept which had developed from medieval Aristotelian metaphysics, and that fit well with natural theology; and the development of the new anti-Aristotelian approach to modern science: as the Enlightenment progressed, evolutionary cosmology and the mechanical philosophy spread from the physical sciences to natural history. Naturalists began to focus on the variability of species; the emergence of palaeontology with the concept of extinction further undermined static views of nature. In the early 19th century prior to Darwinism, Jean-Baptiste Lamarck (1744–1829) proposed his theory of the transmutation of species, the first fully formed theory of evolution.

George Henslow was an Anglican curate, botanist and author. Henslow was notable for being a defender of Lamarckian evolution.

Alternatives to Darwinian evolution have been proposed by scholars investigating biology to explain signs of evolution and the relatedness of different groups of living things. The alternatives in question do not deny that evolutionary changes over time are the origin of the diversity of life, nor that the organisms alive today share a common ancestor from the distant past ; rather, they propose alternative mechanisms of evolutionary change over time, arguing against mutations acted on by natural selection as the most important driver of evolutionary change.