Related Research Articles

The Bill of Rights 1689 is an Act of the Parliament of England that set out certain basic civil rights and changed the succession to the English Crown. It remains a crucial statute in English constitutional law.

Ceduna is a town in South Australia located on the shores of Murat Bay on the coast, west of the Eyre Peninsula. It lies west of the junction of the Flinders and Eyre Highways around 786 km northwest of Adelaide. The nearby port of Thevenard lies 3 km to the west on Cape Thevenard. It is in the District Council of Ceduna, the federal electoral Division of Grey, and the state electoral district of Flinders.

The Wave Hill walk-off, also known as the Gurindji strike, was a walk-off and strike by 200 Gurindji stockmen, house servants and their families, starting on 23 August 1966 and lasting for seven years. It took place at Wave Hill, a cattle station in Kalkarindji, Northern Territory, Australia, and was led by Gurindji man Vincent Lingiari.

Theodor George Henry Strehlow was an Australian anthropologist and linguist. He notably studied the Arrernte Aboriginal Australians and their language in Central Australia.

Rupert Maxwell (Max) Stuart was an Indigenous Australian who was convicted of murder in 1959. His conviction was subject to several appeals to higher courts, the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council, and a Royal Commission, all of which upheld the verdict. Newspapers campaigned successfully against the death sentence being imposed. After serving his sentence, Stuart became an Arrernte elder and from 1998 till 2001 was the chairman of the Central Land Council. In 2002, a film was made about the Stuart case.

Milirrpum v Nabalco Pty Ltd, also known as the Gove land rights case because its subject was land known as the Gove Peninsula in the Northern Territory, was the first litigation on native title in Australia, and the first significant legal case for Aboriginal land rights in Australia, decided on 27 April 1971.

Black and White is a 2002 Australian film directed by Craig Lahiff and starring Robert Carlyle, Charles Dance, Kerry Fox, David Ngoombujarra, and Colin Friels. Louis Nowra wrote the screenplay, and Helen Leake and Nik Powell produced the film. For his performance in the film, Ngoombujarra won an Australian Film Institute award in 2003 as Best Actor in a Supporting Role.

Geoff Clark is an Australian Aboriginal politician and activist. Clark led the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission (ATSIC) from 1999 until it was disbanded in 2004.

The Hindmarsh Island bridge controversy was a 1990s Australian legal and political controversy that involved the clash of local Aboriginal Australian sacred culture and property rights. A proposed bridge to Hindmarsh Island, near Goolwa, South Australia attracted opposition from many local residents, environmental groups and indigenous leaders.

The Hindmarsh Island Royal Commission was a Royal Commission into the nature of female Aboriginal religious beliefs relating to Goolwa and Hindmarsh Island in South Australia that was triggered by the Hindmarsh Island bridge controversy.

The History of Australia (1851–1900) refers to the history of the people of the Australian continent during the 50-year period which preceded the foundation of the Commonwealth of Australia in 1901.

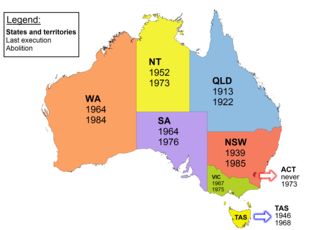

Capital punishment in Australia has been abolished in all jurisdictions since 1985. Queensland abolished the death penalty in 1922. Tasmania did the same in 1968. The Commonwealth abolished the death penalty in 1973, with application also in the Australian Capital Territory and the Northern Territory. Victoria did so in 1975, South Australia in 1976, and Western Australia in 1984. New South Wales abolished the death penalty for murder in 1955, and for all crimes in 1985. In 2010, the Commonwealth Parliament passed legislation prohibiting the re-establishment of capital punishment by any state or territory. Australian law prohibits the extradition or deportation of a prisoner to another jurisdiction if they could be sentenced to death for any crime.

Smoky Bay is a town and locality located in the Australian state of South Australia on the west coast of the Eyre Peninsula. Previously used as a port, the town is now a residential settlement and popular tourist destination known for its recreational fishing, with a boat ramp and jetty located in the town.

The Forrest River massacre was a massacre of Indigenous Australian people by a group of law enforcement personnel and civilians in June 1926, in the wake of the killing of a pastoralist in the Kimberley region of Western Australia.

Michael Wayne Richard was an American man who was convicted of rape and murder. He was executed for his crimes in the state of Texas in 2007. His execution gained notoriety due to controversies regarding procedural problems related to the timing of the execution. Richard admitted he was involved in the murder and offered to help find the murder weapon. Police found the weapon and testing revealed it to be the gun that fired the fatal shot.

The Eyre Peninsula Railway is a 1,067 mm gauge railway on the Eyre Peninsula of South Australia. Radiating out from the ports at Port Lincoln and Thevenard, it is isolated from the rest of the South Australian railway network. It peaked at 777 kilometres in 1950; today only a 60 kilometre section remains open. It is currently operated by Aurizon.

Thomas Sidney Dixon was a Catholic missionary known for his work with Indigenous peoples. He took up the cause of Max Stuart, an Arrernte Aboriginal convicted of murder in 1959.

Rohan Deakin Rivett was an Australian journalist and author, and influential editor of the Adelaide newspaper The News from 1951 to 1960. He is chiefly remembered for accounts of his experiences on the Burma Railway and his activism in the Max Stuart case.

Daniels v Canada (Indian Affairs and Northern Development), 2016 SCC 12 is a case of the Supreme Court of Canada, which ruled that Métis and non-status Indians are "Indians" for the purpose of s 91(24) of the Constitution Act, 1867.

Koonibba is a locality and an associated Aboriginal community in South Australia located about 586 kilometres (364 mi) northwest of the state capital of Adelaide and about 38 km (24 mi) northwest of the municipal seat in Ceduna and 5 km (3.1 mi) north of the Eyre Highway.

References

- ↑ Amos Aikman (2014). "Death of Max Stuart". Missionaries of the Sacred Heart Australia. Retrieved 15 April 2014.

- ↑ R v Stuart [1959 SASR 144, Supreme Court (SA).

- ↑ Stuart v R [1959] HCA 27 , (1959) 101 CLR 1, High Court (Australia)

- 1 2 3 "Report of the Royal Commission in regard to Rupert Max Stuart" (PDF). 3 December 1959. Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 March 2018 – via Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies.

- 1 2 3 4 Alan Sharpe, Vivien Encel (2003). Murder!: 25 true Australian crimes. Pages 80–88: Kingsclear Books. ISBN 0-908272-47-2.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - ↑ Inglis, K. S. (2002) [1961]. The Stuart Case (2nd ed.). Melbourne, Australia: Black Inc. pp. 62–63. ISBN 1-86395-243-8.

- ↑ J. Churches (2002). "MS 3764 Father Dixon and the Stuart Case". Manuscript finding aids. Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies (AIATSIS) www.aiatsis.gov.au. Archived from the original on 21 August 2006. Retrieved 21 February 2006.

- ↑ Peter Alexander (2002). "Rupert Maxwell Stuart: the facts". Police Journal Online. Police Association of South Australia. Archived from the original on 27 September 2007. Retrieved 20 February 2006.

- ↑ Geoffrey Robertson QC (1 April 2006). "Politics, Power, Justice and the Media: controversies from the Stuart Case". University of Adelaide . Retrieved 17 January 2010.