Basque is the only surviving Paleo-European language spoken in Europe, predating the arrival of speakers of the Indo-European languages that dominate the continent today. Basque is spoken by the Basques and other residents of the Basque Country, a region that straddles the westernmost Pyrenees in adjacent parts of northern Spain and southwestern France. Basque is classified as a language isolate. The Basques are indigenous to and primarily inhabit the Basque Country. The Basque language is spoken by 806,000 Basques in all territories. Of these, 93.7% (756,000) are in the Spanish area of the Basque Country and the remaining 6.3% (50,000) are in the French portion. Basque is considered the most spoken language isolate in the world.

The mythology of the ancient Basques largely did not survive the arrival of Christianity in the Basque Country between the 4th and 12th century AD. Most of what is known about elements of this original belief system is based on the analysis of legends, the study of place names and scant historical references to pagan rituals practised by the Basques.

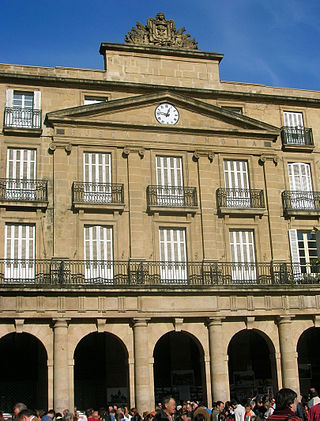

Euskaltzaindia is the official academic language regulatory institution which watches over the Basque language. It conducts research, seeks to protect the language, and establishes standards of use. It is known in Spanish as La Real Academia de la Lengua Vasca and in French as Académie de la Langue Basque.

The Aquitanian language was the language of the ancient Aquitani, spoken on both sides of the western Pyrenees in ancient Aquitaine and in the areas south of the Pyrenees in the valleys of the Basque Country before the Roman conquest. It probably survived in Aquitania north of the Pyrenees until the Early Middle Ages.

The Basque alphabet is a Latin alphabet used to write the Basque language. It consists of 27 letters.

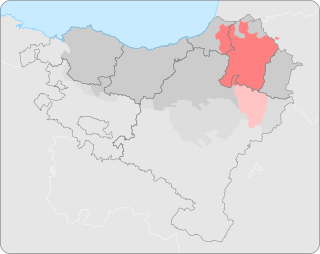

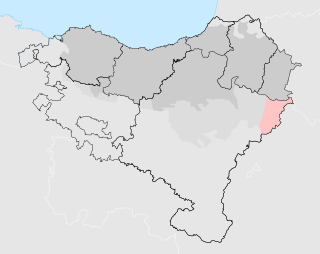

The French Basque Country, or Northern Basque Country, is a region lying on the west of the French department of the Pyrénées-Atlantiques. Since 1 January 2017, it constitutes the Basque Municipal Community presided over by Jean-René Etchegaray.

Biscayan, sometimes Bizkaian, is a dialect of the Basque language spoken mainly in Biscay, one of the provinces of the Basque Country of Spain.

Standard Basque is a standardised version of the Basque language, developed by the Basque Language Academy in the late 1960s, which nowadays is the most widely and commonly spoken Basque-language version throughout the Basque Country. Heavily based on the literary tradition of the central areas, it is the version of the language that is commonly used in education at all levels, from elementary school to university, on television and radio, and in the vast majority of all written production in Basque.

Koldo Mitxelena Elissalt was an eminent Spanish Basque linguist. He taught in the Department of Philology at the University of the Basque Country, and was a member of the Royal Academy of the Basque Language.

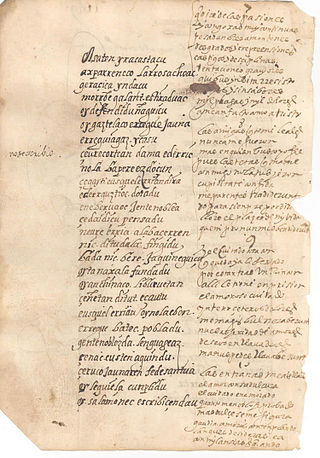

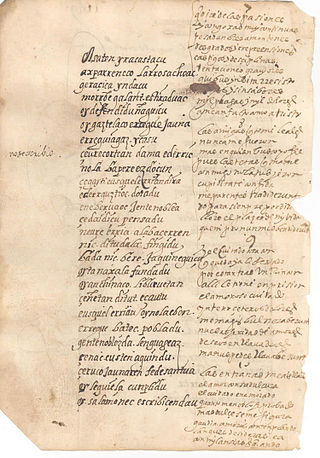

Although the first instances of coherent Basque phrases and sentences go as far back as the San Millán glosses of around 950, the large-scale damage done by periods of great instability and warfare, such as the clan wars of the Middle Ages, the Carlist Wars and the Spanish Civil War, led to the scarcity of written material predating the 16th century.

Basque dialects are linguistic varieties of the Basque language which differ in pronunciation, vocabulary and grammar from each other and from Standard Basque. Between six and nine Basque dialects have been historically distinguished:

Resurrección María de Azkue was an influential Basque priest, musician, poet, writer, sailor and academic. He made several major contributions to the study of the Basque language and was the first head of the Euskaltzaindia, the Academy of the Basque Language. In spite of some justifiable criticism of an imbalance towards unusual and archaic forms and a tendency to ignore the Romance influence on Basque, he is considered one of the greatest scholars of Basque to date.

Erromintxela is the distinctive language of a group of Romani living in the Basque Country, who also go by the name Erromintxela. It is sometimes called Basque Caló or Errumantxela in English; caló vasco, romaní vasco, or errominchela in Spanish; and euskado-rromani or euskado-romani in French. Although detailed accounts of the language date to the end of the 19th century, linguistic research began only in the 1990s.

Koldo Zuazo is a Basque linguist, professor at the University of the Basque Country and specialist in Basque language dialectology and sociolinguistics.

Joxe Azurmendi Otaegi is a Basque writer, philosopher, essayist and poet. He has published numerous articles and books on ethics, politics, the philosophy of language, technique, Basque literature and philosophy in general.

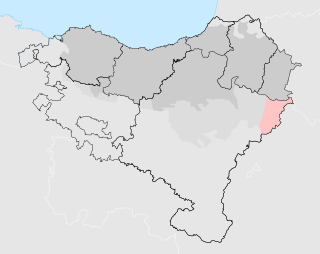

Roncalese is an extinct Basque dialect once spoken in the Roncal Valley in Navarre, Spain. It is a subdialect of Eastern Navarrese in the classification of Koldo Zuazo. It had been classified as a subdialect of Souletin in the 19th-century classification of Louis Lucien Bonaparte, and as a separate dialect in the early-20th-century classification of Resurrección María de Azkue. The last speaker of the Roncalese, Fidela Bernat, died in 1991.

Alavese is an extinct dialect of the Basque language spoken formerly in Álava, one of the provinces of the Basque Country of Spain. The modern-day communities of Aramaio and Legutio along the northern border with Biscay do not speak the Alavese dialect but a variant of the Biscayan dialect instead and while overall some 25% of people in Álava today are Basque speakers, the majority of these are speakers of Standard Basque who acquired Basque via the education system or moved there from other parts of the Basque Country.

Joseba Agirreazkuenaga is a researcher and historian. He is specialist in the history of the Basque Country particularly: the crisis of the Ancien Régime; the fueros, self-governance, the economic concert between Spain and the Autonomous Community of the Basque Country and its fiscal system, and the social movements both in Bilbao and in the Basque Country as a whole.

The Euskal Hiztegi Historiko-Etimologikoa is a historical and etymological dictionary of Basque, published by the Royal Academy of the Basque language, edited by Joseba Lakarra, Julen Manterola, and Iñaki Segurola. It is the first comprehensive historical and etymological Basque dictionary.

16th-century Basque literature begins with three authors considered classics: Joan Perez de Lazarraga, Bernard Etxepare and Joanes Leizarraga. In the manuscript of the first of them, discovered in 2004, the influence of the traditional court lyric, the Italian novela pastoril and the popular Basque templates can be observed. In the case of Etxepare, often compared to the Archpriest of Hita, the influence of French literature has been mentioned. Regarding Leizarraga, translator into Basque of the New Testament and other works on religious themes, he stands out for his attempt to find a unified language—a concern of many of the later authors—and for his use of cultured verbal forms and compound sentences, nonexistent in written literature up to that time.