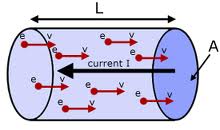

An electric current is a flow of charged particles, such as electrons or ions, moving through an electrical conductor or space. It is defined as the net rate of flow of electric charge through a surface. The moving particles are called charge carriers, which may be one of several types of particles, depending on the conductor. In electric circuits the charge carriers are often electrons moving through a wire. In semiconductors they can be electrons or holes. In an electrolyte the charge carriers are ions, while in plasma, an ionized gas, they are ions and electrons.

A diode is a two-terminal electronic component that conducts current primarily in one direction. It has low resistance in one direction and high resistance in the other.

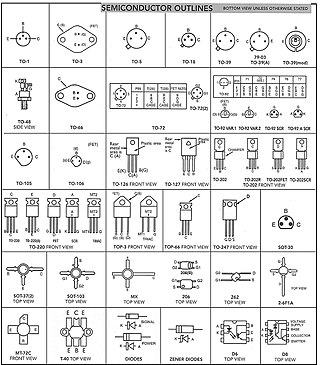

A transistor is a semiconductor device used to amplify or switch electrical signals and power. It is one of the basic building blocks of modern electronics. It is composed of semiconductor material, usually with at least three terminals for connection to an electronic circuit. A voltage or current applied to one pair of the transistor's terminals controls the current through another pair of terminals. Because the controlled (output) power can be higher than the controlling (input) power, a transistor can amplify a signal. Some transistors are packaged individually, but many more in miniature form are found embedded in integrated circuits. Because transistors are the key active components in practically all modern electronics, many people consider them one of the 20th century's greatest inventions.

A semiconductor device is an electronic component that relies on the electronic properties of a semiconductor material for its function. Its conductivity lies between conductors and insulators. Semiconductor devices have replaced vacuum tubes in most applications. They conduct electric current in the solid state, rather than as free electrons across a vacuum or as free electrons and ions through an ionized gas.

In electronics, the metal–oxide–semiconductor field-effect transistor is a type of field-effect transistor (FET), most commonly fabricated by the controlled oxidation of silicon. It has an insulated gate, the voltage of which determines the conductivity of the device. This ability to change conductivity with the amount of applied voltage can be used for amplifying or switching electronic signals. The term metal–insulator–semiconductor field-effect transistor (MISFET) is almost synonymous with MOSFET. Another near-synonym is insulated-gate field-effect transistor (IGFET).

The junction field-effect transistor (JFET) is one of the simplest types of field-effect transistor. JFETs are three-terminal semiconductor devices that can be used as electronically controlled switches or resistors, or to build amplifiers.

A bipolar junction transistor (BJT) is a type of transistor that uses both electrons and electron holes as charge carriers. In contrast, a unipolar transistor, such as a field-effect transistor (FET), uses only one kind of charge carrier. A bipolar transistor allows a small current injected at one of its terminals to control a much larger current between the remaining two terminals, making the device capable of amplification or switching.

Space charge is an interpretation of a collection of electric charges in which excess electric charge is treated as a continuum of charge distributed over a region of space rather than distinct point-like charges. This model typically applies when charge carriers have been emitted from some region of a solid—the cloud of emitted carriers can form a space charge region if they are sufficiently spread out, or the charged atoms or molecules left behind in the solid can form a space charge region.

Wide-bandgap semiconductors are semiconductor materials which have a larger band gap than conventional semiconductors. Conventional semiconductors like Silicon and Selenium have a bandgap in the range of 0.7 – 1.5 electronvolt (eV), whereas wide-bandgap materials have bandgaps in the range above 2 eV. Generally, wide-bandgap semiconductors have electronic properties which fall in between those of conventional semiconductors and insulators.

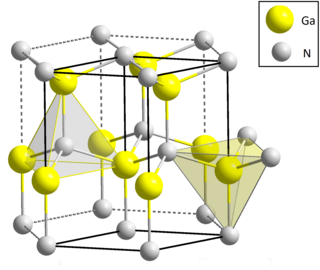

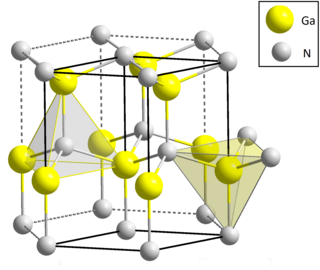

Gallium nitride is a binary III/V direct bandgap semiconductor commonly used in blue light-emitting diodes since the 1990s. The compound is a very hard material that has a Wurtzite crystal structure. Its wide band gap of 3.4 eV affords it special properties for applications in optoelectronic, high-power and high-frequency devices. For example, GaN is the substrate that makes violet (405 nm) laser diodes possible, without requiring nonlinear optical frequency doubling.

In solid-state physics, the electron mobility characterises how quickly an electron can move through a metal or semiconductor when pushed or pulled by an electric field. There is an analogous quantity for holes, called hole mobility. The term carrier mobility refers in general to both electron and hole mobility.

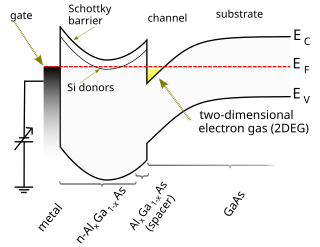

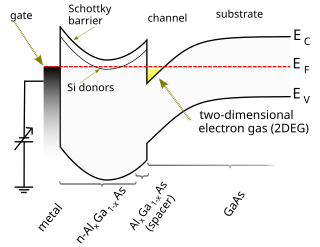

A high-electron-mobility transistor, also known as heterostructure FET (HFET) or modulation-doped FET (MODFET), is a field-effect transistor incorporating a junction between two materials with different band gaps as the channel instead of a doped region. A commonly used material combination is GaAs with AlGaAs, though there is wide variation, dependent on the application of the device. Devices incorporating more indium generally show better high-frequency performance, while in recent years, gallium nitride HEMTs have attracted attention due to their high-power performance.

A Gunn diode, also known as a transferred electron device (TED), is a form of diode, a two-terminal semiconductor electronic component, with negative differential resistance, used in high-frequency electronics. It is based on the "Gunn effect" discovered in 1962 by physicist J. B. Gunn. Its main uses are in electronic oscillators to generate microwaves, in applications such as radar speed guns, microwave relay data link transmitters, and automatic door openers.

In semiconductor physics, the depletion region, also called depletion layer, depletion zone, junction region, space charge region, or space charge layer, is an insulating region within a conductive, doped semiconductor material where the mobile charge carriers have diffused away, or forced away by an electric field. The only elements left in the depletion region are ionized donor or acceptor impurities. This region of uncovered positive and negative ions is called the depletion region due to the depletion of carriers in this region, leaving none to carry a current. Understanding the depletion region is key to explaining modern semiconductor electronics: diodes, bipolar junction transistors, field-effect transistors, and variable capacitance diodes all rely on depletion region phenomena.

Hot carrier injection (HCI) is a phenomenon in solid-state electronic devices where an electron or a “hole” gains sufficient kinetic energy to overcome a potential barrier necessary to break an interface state. The term "hot" refers to the effective temperature used to model carrier density, not to the overall temperature of the device. Since the charge carriers can become trapped in the gate dielectric of a MOS transistor, the switching characteristics of the transistor can be permanently changed. Hot-carrier injection is one of the mechanisms that adversely affects the reliability of semiconductors of solid-state devices.

Velocity overshoot is a physical effect resulting in transit times for charge carriers between terminals that are smaller than the time required for emission of an optical phonon. The velocity therefore exceeds the saturation velocity up to three times, which leads to faster field-effect transistor or bipolar transistor switching. The effect is noticeable in the ordinary field-effect transistor for the gates shorter than 100 nm.

In solid-state physics, the Poole–Frenkel effect is a model describing the mechanism of trap-assisted electron transport in an electrical insulator. It is named after Yakov Frenkel, who published on it in 1938, extending the theory previously developed by H. H. Poole.

In physics, the field effect refers to the modulation of the electrical conductivity of a material by the application of an external electric field.

The field-effect transistor (FET) is a type of transistor that uses an electric field to control the current through a semiconductor. It comes in two types: junction FET (JFET) and metal-oxide-semiconductor FET (MOSFET). FETs have three terminals: source, gate, and drain. FETs control the current by the application of a voltage to the gate, which in turn alters the conductivity between the drain and source.

In solid-state physics, band bending refers to the process in which the electronic band structure in a material curves up or down near a junction or interface. It does not involve any physical (spatial) bending. When the electrochemical potential of the free charge carriers around an interface of a semiconductor is dissimilar, charge carriers are transferred between the two materials until an equilibrium state is reached whereby the potential difference vanishes. The band bending concept was first developed in 1938 when Mott, Davidov and Schottky all published theories of the rectifying effect of metal-semiconductor contacts. The use of semiconductor junctions sparked the computer revolution in the second half of the 20th century. Devices such as the diode, the transistor, the photocell and many more play crucial roles in technology.