Related Research Articles

Ardipithecus is a genus of an extinct hominine that lived during the Late Miocene and Early Pliocene epochs in the Afar Depression, Ethiopia. Originally described as one of the earliest ancestors of humans after they diverged from the chimpanzees, the relation of this genus to human ancestors and whether it is a hominin is now a matter of debate. Two fossil species are described in the literature: A. ramidus, which lived about 4.4 million years ago during the early Pliocene, and A. kadabba, dated to approximately 5.6 million years ago. Initial behavioral analysis indicated that Ardipithecus could be very similar to chimpanzees, however more recent analysis based on canine size and lack of canine sexual dimorphism indicates that Ardipithecus was characterised by reduced aggression, and that they more closely resemble bonobos.

Bipedalism is a form of terrestrial locomotion where a tetrapod moves by means of its two rear limbs or legs. An animal or machine that usually moves in a bipedal manner is known as a biped, meaning 'two feet'. Types of bipedal movement include walking or running and hopping.

Homininae, also called "African hominids" or "African apes", is a subfamily of Hominidae. It includes two tribes, with their extant as well as extinct species: 1) the tribe Hominini ―and 2) the tribe Gorillini (gorillas). Alternatively, the genus Pan is sometimes considered to belong to its own third tribe, Panini. Homininae comprises all hominids that arose after orangutans split from the line of great apes. The Homininae cladogram has three main branches, which lead to gorillas, and to humans and chimpanzees via the tribe Hominini and subtribes Hominina and Panina. There are two living species of Panina and two living species of gorillas, but only one extant human species. Traces of extinct Homo species, including Homo floresiensis have been found with dates as recent as 40,000 years ago. Organisms in this subfamily are described as hominine or hominines.

Orrorin is an extinct genus of primate within Homininae from the Miocene Lukeino Formation and Pliocene Mabaget Formation, both of Kenya.

Australopithecus is a genus of early hominins that existed in Africa during the Pliocene and Early Pleistocene. The genera Homo, Paranthropus, and Kenyanthropus evolved from some Australopithecus species. Australopithecus is a member of the subtribe Australopithecina, which sometimes also includes Ardipithecus, though the term "australopithecine" is sometimes used to refer only to members of Australopithecus. Species include A. garhi, A. africanus, A. sediba, A. afarensis, A. anamensis, A. bahrelghazali and A. deyiremeda. Debate exists as to whether some Australopithecus species should be reclassified into new genera, or if Paranthropus and Kenyanthropus are synonymous with Australopithecus, in part because of the taxonomic inconsistency.

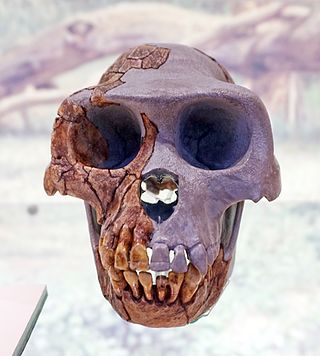

Australopithecus afarensis is an extinct species of australopithecine which lived from about 3.9–2.9 million years ago (mya) in the Pliocene of East Africa. The first fossils were discovered in the 1930s, but major fossil finds would not take place until the 1970s. From 1972 to 1977, the International Afar Research Expedition—led by anthropologists Maurice Taieb, Donald Johanson and Yves Coppens—unearthed several hundreds of hominin specimens in Hadar, Ethiopia, the most significant being the exceedingly well-preserved skeleton AL 288-1 ("Lucy") and the site AL 333. Beginning in 1974, Mary Leakey led an expedition into Laetoli, Tanzania, and notably recovered fossil trackways. In 1978, the species was first described, but this was followed by arguments for splitting the wealth of specimens into different species given the wide range of variation which had been attributed to sexual dimorphism. A. afarensis probably descended from A. anamensis and is hypothesised to have given rise to Homo, though the latter is debated.

Paleoanthropology or paleo-anthropology is a branch of paleontology and anthropology which seeks to understand the early development of anatomically modern humans, a process known as hominization, through the reconstruction of evolutionary kinship lines within the family Hominidae, working from biological evidence and cultural evidence.

Laetoli is a pre-historic site located in Enduleni ward of Ngorongoro District in Arusha Region, Tanzania. The site is dated to the Plio-Pleistocene and famous for its Hominina footprints, preserved in volcanic ash. The site of the Laetoli footprints is located 45 km south of Olduvai gorge. The location and tracks were discovered by archaeologist Mary Leakey and her team in 1976, and were excavated by 1978. Based on analysis of the footfall impressions "The Laetoli Footprints" provided convincing evidence for the theory of bipedalism in Pliocene Hominina and received significant recognition by scientists and the public. Since 1998, paleontological expeditions have continued under the leadership of Amandus Kwekason of the National Museum of Tanzania and Terry Harrison of New York University, leading to the recovery of more than a dozen new Hominina finds, as well as a comprehensive reconstruction of the paleoecology. The site is a registered National Historic Sites of Tanzania.

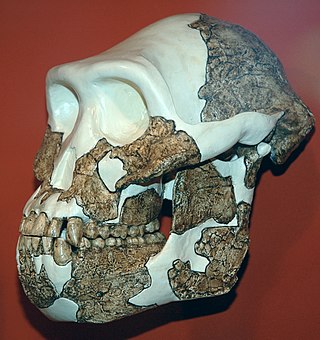

Australopithecus africanus is an extinct species of australopithecine which lived between about 3.3 and 2.1 million years ago in the Late Pliocene to Early Pleistocene of South Africa. The species has been recovered from Taung, Sterkfontein, Makapansgat, and Gladysvale. The first specimen, the Taung child, was described by anatomist Raymond Dart in 1924, and was the first early hominin found. However, its closer relations to humans than to other apes would not become widely accepted until the middle of the century because most had believed humans evolved outside of Africa. It is unclear how A. africanus relates to other hominins, being variously placed as ancestral to Homo and Paranthropus, to just Paranthropus, or to just P. robustus. The specimen "Little Foot" is the most completely preserved early hominin, with 90% of the skeleton intact, and the oldest South African australopith. However, it is controversially suggested that it and similar specimens be split off into "A. prometheus".

Australopithecus anamensis is a hominin species that lived approximately between 4.2 and 3.8 million years ago and is the oldest known Australopithecus species, living during the Plio-Pleistocene era.

Orthograde is a term derived from Greek ὀρθός, orthos + Latin gradi that describes a manner of walking which is upright, with the independent motion of limbs. Both New and Old World monkeys are primarily arboreal, and they have a tendency to walk with their limbs swinging in parallel to one another. This differs from the manner of walking demonstrated by the apes.

Australopithecina or Hominina is a subtribe in the tribe Hominini. The members of the subtribe are generally Australopithecus, and it typically includes the earlier Ardipithecus, Orrorin, Sahelanthropus, and (sometimes) Graecopithecus. All these closely related species are now sometimes collectively termed australopiths or homininians. They are the extinct, close relatives of modern humans and, together with the extant genus Homo, comprise the human clade. Members of the human clade, i.e. the Hominini after the split from the chimpanzees, are now called Hominina.

Australopithecus bahrelghazali is an extinct species of australopithecine discovered in 1995 at Koro Toro, Bahr el Gazel, Chad, existing around 3.5 million years ago in the Pliocene. It is the first and only australopithecine known from Central Africa, and demonstrates that this group was widely distributed across Africa as opposed to being restricted to East and southern Africa as previously thought. The validity of A. bahrelghazali has not been widely accepted, in favour of classifying the specimens as A. afarensis, a better known Pliocene australopithecine from East Africa, because of the anatomical similarity and the fact that A. bahrelghazali is known only from 3 partial jawbones and an isolated premolar. The specimens inhabited a lakeside grassland environment with sparse tree cover, possibly similar to the modern Okavango Delta, and similarly predominantly ate C4 savanna foods—such as grasses, sedges, storage organs, or rhizomes—and to a lesser degree also C3 forest foods—such as fruits, flowers, pods, or insects. However, the teeth seem ill-equipped to process C4 plants, so its true diet is unclear.

Aramis is a village and archaeological site in north-eastern Ethiopia, where remains of Australopithecus and Ardipithecus have been found. The village is located in Administrative Zone 5 of the Afar Region, which is part of the Afar Sultanate of Dawe, with a latitude and longitude of 10°30′N40°30′E, and is part of the, Carri Rasuk, Xaale Faagê Daqaara.

Ardipithecus kadabba is the scientific classification given to fossil remains "known only from teeth and bits and pieces of skeletal bones", originally estimated to be 5.8 to 5.2 million years old, and later revised to 5.77 to 5.54 million years old. According to the first description, these fossils are close to the common ancestor of chimps and humans. Their development lines are estimated to have parted 6.5–5.5 million years ago. It has been described as a "probable chronospecies" of A. ramidus. Although originally considered a subspecies of A. ramidus, in 2004 anthropologists Yohannes Haile-Selassie, Gen Suwa, and Tim D. White published an article elevating A. kadabba to species level on the basis of newly discovered teeth from Ethiopia. These teeth show "primitive morphology and wear pattern" which demonstrate that A. kadabba is a distinct species from A. ramidus.

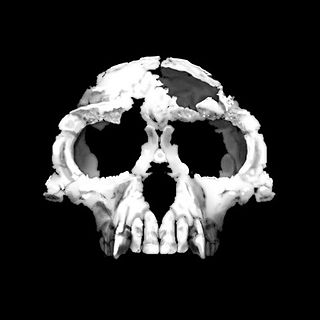

Ardipithecus ramidus is a species of australopithecine from the Afar region of Early Pliocene Ethiopia 4.4 million years ago (mya). A. ramidus, unlike modern hominids, has adaptations for both walking on two legs (bipedality) and life in the trees (arboreality). However, it would not have been as efficient at bipedality as humans, nor at arboreality as non-human great apes. Its discovery, along with Miocene apes, has reworked academic understanding of the chimpanzee–human last common ancestor from appearing much like modern-day chimpanzees, orangutans and gorillas to being a creature without a modern anatomical cognate.

The evolution of human bipedalism, which began in primates approximately four million years ago, or as early as seven million years ago with Sahelanthropus, or approximately twelve million years ago with Danuvius guggenmosi, has led to morphological alterations to the human skeleton including changes to the arrangement, shape, and size of the bones of the foot, hip, knee, leg, and the vertebral column. These changes allowed for the upright gait to be overall more energy efficient in comparison to quadrupeds. The evolutionary factors that produced these changes have been the subject of several theories that correspond with environmental changes on a global scale.

Ardi (ARA-VP-6/500) is the designation of the fossilized skeletal remains of an Ardipithecus ramidus, thought to be an early human-like female anthropoid 4.4 million years old. It is the most complete early hominid specimen, with most of the skull, teeth, pelvis, hands and feet, more complete than the previously known Australopithecus afarensis specimen called "Lucy". In all, 125 different pieces of fossilized bone were found.

Claude Owen Lovejoy is an evolutionary anthropologist and anatomist at Kent State University Ohio. He is best known for his work on Australopithecine locomotion and the origins of bipedalism. "The origin of man", which he published in Science in January 1981, is cited as among his best-known articles. The 'C' of his name stands for Claude, but he never uses the name and is known only as Owen.

The Middle Awash Project is an international research expedition conducted in the Afar Region of Ethiopia with the goal of determining the olrigins of humanity. The project has the approval of the Ethiopian Culture Ministry and a strong commitment to developing Ethiopian archaeology, paleontology and geology research infrastructure. This project has discovered over 260 fossil specimens and over 17,000 vertebrate fossil specimens to date ranging from 200,000 to 6,000,000 years in age. Researchers have discovered the remains of four hominin species, the earliest subspecies of homo sapiens as well as stone tools. All specimens are permanently held at the National Museum of Ethiopia, where the project’s laboratory work is conducted year round.

References

- ↑ Richmond, G. B., Begun, R. D., and Strait, D. S. (2001): 'Origin of Human Bipedalism: The Knuckle-Walking Hypothesis Revisited' in Yearbook of Physical Anthropology

- ↑ Lamarck, J.B. de (1809): Philosophie zoologique, ou Exposition des considérations relative à l'histoire naturelle des animaux, Dentu

- ↑ Darwin, C.R. (1871): The Descent of Man, and Selection in Relation to Sex, John Murray

- ↑ Wallace, A.R. (1889): Darwinism. An Exposition of the Theory of Natural Selection with Some of Its Applications, Macmillan and Co.

- ↑ Steinmann, G. (1908): Die geologischen Grundlagen der Abstammungslehre, W. Engelmann

- ↑ Osborn, H.F. (1915): Men of the Old Stone Age. Their Environment, Life and Art, Charles Scribner's Sons

- ↑ Hilzheimer, O.J.M. (1921): 'Aphoristische Gedanken über einen Zusammenhang zwischen Erdgeschichte, Biologie, Menschheitsgeschichte und Kulturgeschichte' in Zeitschrift für Morphologie und Anthropologie, 21, p. 185-208

- ↑ Dart, Raymond (7 February 1925). "Australopithecus africanus: The Man-Ape of South Africa" (PDF). Nature. 115 (2884): 195–199. Bibcode:1925Natur.115..195D. doi: 10.1038/115195a0 . S2CID 4142569 . Retrieved 26 September 2017.

- ↑ Weinert, H. (1932): Ursprung der Menschheit. Über den engeren Anschluss des Menschengeschlechts an die Menschenaffen, Ferdinand Enke

- ↑ Grabau, A.W. (1961): The World We Live in. A New Interpretation of Earth History, Geological Society of China

- ↑ Weidenreich, F. (1939): 'Six Lectures on Sinanthropus Pekinensis and Related Problems' in Bulletin of the Geological Society of China, Volume 19, p. 1-92

- 1 2 Shreeve, James (1 July 1996). "Sunset on the Savanna". Discover. 17 (7). Archived from the original on 28 September 2017. Retrieved 26 September 2017.

- ↑ Richmond, Brian; Strait, David (23 March 2000). "Evidence that humans evolved from a knuckle-walking ancestor". Nature. 404 (6776): 382–385. Bibcode:2000Natur.404..382R. doi:10.1038/35006045. PMID 10746723. S2CID 4303978.

- ↑ Falk, Dean (22 February 2000). Primate Diversity (2 ed.). New York: W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0393974287 . Retrieved 26 September 2017.

- ↑ Wheeler, P. E. (1 January 1984). "The evolution of bipedality and loss of functional body hair in hominids". Journal of Human Evolution. 13 (1): 91–98. doi:10.1016/S0047-2484(84)80079-2.

- ↑ Robinson J.T. (1963): 'Adaptive radiation in the Australopithecines and the origin of man' in Howell, F.C.; Bourlière, F. African Ecology and Human Evolution, Aldine, p. 385-416

- ↑ Monod, T. (1963): 'Late Tertiary and Pleistocene in the Sahara' in Howell; Bourlière, p. 117–229

- ↑ Jolly, C.J. (1970): 'The Seed-Eaters: A New Model of Hominid Differentiation Based on a Baboon Analogy' in Man, Volume 5, p. 5–26

- ↑ Lovejoy, C.O. (1981): 'The Origin of Man' in Science, Volume 211, Number 4480, p. 341-350

- ↑ Kortlandt, A. (1972): New Perspectives on Ape and Human Evolution, Stichting voor Psychobiologie

- ↑ Coppens, Y. (1994): 'East Side Story: The Origin of Humankind' in Scientific American, Volume 270, no. 5, p. 88-95

- ↑ Green, Alemseged, David, Zeresenay (2017). "Australopithecus afarensis Scapular Ontogeny, Function, and the Role of Climbing in Human Evolution". Science. 338 (6106): 514–517. doi:10.1126/science.1227123. PMID 23112331. S2CID 206543814.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Thorpe, S. K.; Holder, R.L; Crompton, R. H. (2007). "Origin of human bipedalism as an adaptation for locomotion on flexible branches". Science. 316 (5829): 1328–31. Bibcode:2007Sci...316.1328T. doi:10.1126/science.1140799. PMID 17540902. S2CID 85992565.

- ↑ White, T.D.; Suwa, G.; Asfaw, B. (1994): 'Australopithecus ramidus, a new species of early hominid from Aramis, Ethiopia' in Nature, Volume 371, p. 306–312

- ↑ White, T.D.; Asfaw, B.; Beyene, Y.; Haile-Selassie, Y.; Lovejoy, C.O.; Suwa, G.; WoldeGabriel, G. (2009): 'Ardipithecus ramidus and the Paleobiology of Early Hominids' in Science, Volume 326, p. 75-86

- ↑ Cerling, T.E.; Levin, N.E.; Quade, J.; Wynn, J.G.; Fox, D.L.; Kingston, J.D.; Klein, R.G.; Brown, F.H. (2010): 'Comment on the Paleoenvironment of Ardipithecus ramidus' in Science, Volume 328, 1105

- ↑ Vaneechoutte, M.; Kuliukas, A.; Verhaegen, M. (2011): Was Man More Aquatic in the Past? Fifty Years After Alister Hardy – Waterside Hypotheses of Human Evolution, Bentham Science Publishers

- ↑ Pickford, M.; Senut, B. (2001): 'The geological and faunal context of Late Miocene hominid remains from Lukeino, Kenya' in Comptes Rendus de l’Academie des Sciences, Series IIA, Earth and Planetary Science, Volume 332, No. 2, p. 145-152

- ↑ Senut, B. (2015): 'Morphology and environment in some fossil Hominoids and Pedetids (Mammalia)' in Journal of Anatomy, Volume 228, Issue 4

- ↑ Vignaud, P. et al. (2002): 'Geology and palaeontology of the Upper Miocene Toros-Menalla hominid locality, Chad' in Nature, Volume 418, p. 152-155

- ↑ Su, D.F.; Ambrose, S.H.; DeGusta, D.; Haile-Selassie, Y. (2009): 'Paleoenvironment' in Haile-Selassie, Y.; WoldeGabriel, G. Ardipithecus Kadabba. Late Miocene Evidence from the Middle Awash, Ethiopia, University of California Press

- ↑ Cerling, T.E.; Wynn, J.G.; Andanje, S.A.; Bird, M.I.; Korir, D.K.; Levin, N.E.; Mace, W.; Macharia, A.N.; Quade, J.; Remien, C.H. (2011): 'Woody cover and hominin environments in the past 6 million years' in Nature, Volume 476, p. 51-56

- ↑ Domínguez-Rodrigo, M. (2014): 'Is the “Savanna Hypothesis” a Dead Concept for Explaining the Emergence of the Earliest Hominins?' in Current Anthropology, Volume 55, Number 1, p. 59-81