A pheromone is a secreted or excreted chemical factor that triggers a social response in members of the same species. Pheromones are chemicals capable of acting like hormones outside the body of the secreting individual, to affect the behavior of the receiving individuals. There are alarm pheromones, food trail pheromones, sex pheromones, and many others that affect behavior or physiology. Pheromones are used by many organisms, from basic unicellular prokaryotes to complex multicellular eukaryotes. Their use among insects has been particularly well documented. In addition, some vertebrates, plants and ciliates communicate by using pheromones. The ecological functions and evolution of pheromones are a major topic of research in the field of chemical ecology.

Urination is the release of urine from the bladder to the outside of the body. Urine is released through the urethra and exits the penis or vulva through the urinary meatus in placental mammals, but is released through the cloaca in other vertebrates. It is the urinary system's form of excretion. It is also known medically as micturition, voiding, uresis, or, rarely, emiction, and known colloquially by various names including peeing, weeing, pissing, and euphemistically number one. The process of urination is under voluntary control in healthy humans and other animals, but may occur as a reflex in infants, some elderly individuals, and those with neurological injury. It is normal for adult humans to urinate up to seven times during the day.

In ethology, territory is the sociographical area that an animal consistently defends against conspecific competition using agonistic behaviors or real physical aggression. Animals that actively defend territories in this way are referred to as being territorial or displaying territorialism.

The white-tailed deer, also known commonly as the whitetail and the Virginia deer, is a medium-sized species of deer native to North America, Central America, and South America as far south as Peru and Bolivia, where it predominately inhabits high mountain terrains of the Andes. It has also been introduced to New Zealand, all the Greater Antilles in the Caribbean, and some countries in Europe, such as the Czech Republic, Finland, France, Germany, Romania and Serbia. In the Americas, it is the most widely distributed wild ungulate.

The mule deer is a deer indigenous to western North America; it is named for its ears, which are large like those of the mule. Two subspecies of mule deer are grouped into the black-tailed deer.

The rut is the mating season of certain mammals, which includes ruminants such as deer, sheep, camels, goats, pronghorns, bison, giraffes and antelopes, and extends to others such as skunks and elephants. The rut is characterized in males by an increase in testosterone, exaggerated sexual dimorphisms, increased aggression, and increased interest in females. The males of the species may mark themselves with mud, undergo physiological changes or perform characteristic displays in order to make themselves more visually appealing to the females. Males also use olfaction to entice females to mate using secretions from glands and soaking in their own urine. Deer will also leave their own personal scent marking around by urinating down their own legs with the urine soaking the hair that covers their tarsal glands. Male deer do these most often during breeding season.

Black-tailed deer or blacktail deer occupy coastal regions of western North America. There are two subspecies, the Columbian black-tailed deer which ranges from Northern California into the Pacific Northwest of the United States and coastal British Columbia in Canada., and a second subspecies known as the Sitka deer which is geographically disjunct occupying from mid-coastal British Columbia up through southeast Alaska, and southcentral Alaska. The black-tailed deer subspecies are about half the size of the mainland mule deer subspecies, the latter ranging further east in the western United States. They have sometimes been treated as a distinct species, but virtually all recent authorities maintain black-tailed deer are mule deer subspecies.

Dog communication is the transfer of information between dogs, as well as between dogs and humans. Behaviors associated with dog communication are categorized into visual and vocal. Visual communication includes mouth shape and head position, licking and sniffing, ear and tail positioning, eye gaze, facial expression, and body posture. Dog vocalizations, or auditory communication, can include barks, growls, howls, whines and whimpers, screams, pants and sighs. Dogs also communicate via gustatory communication, utilizing scent and pheromones.

The anal glands or anal sacs are small glands near the anus in many mammals. They are situated in between the external anal sphincter muscle and internal anal sphincter muscle. In non-human mammals, the secretions of the anal glands contain mostly volatile organic compounds with a strong odor, and they are thus functionally involved in communication. Depending upon the species, they may be involved in territory marking, individual identification, and sexual signalling, as well as defense. Their function in humans is unclear.

The violet gland or supracaudal gland is a gland located on the upper surface of the tail of certain mammals, including European badgers and canids such as foxes, wolves, and the domestic dog, as well as the domestic cat. Like many other mammalian secretion glands, the violet gland consists of modified sweat glands and sebaceous glands.

An animal repellent consists of any object or method made with the intention of keeping animals away from personal items as well as food, plants or yourself. Plants and other living organisms naturally possess a special ability to emit chemicals known as semiochemicals as a way to defend themselves from predators. Humans purposely make use of some of those and create a way to repel animals through various forms of protection.

Cats communicate for a variety of reasons, including to show happiness, express anger, solicit attention, and observe potential prey. Additionally, they collaborate, play, and share resources. When cats communicate with humans, they do so to get what they need or want, such as food, water, attention, or play. As such, cat communication methods have been significantly altered by domestication. Studies have shown that domestic cats tend to meow much more than feral cats. They rarely meow to communicate with fellow cats or other animals. Cats can socialize with each other and are known to form "social ladders," where a dominant cat is leading a few lesser cats. This is common in multi-cat households.

A cat pheromone is a chemical molecule, or compound, that is used by cats and other felids for communication. These pheromones are produced and detected specifically by the body systems of cats and evoke certain behavioural responses.

The preorbital gland is a paired exocrine gland found in many species of artiodactyls, which is homologous to the lacrimal gland found in humans. These glands are trenchlike slits of dark blue to black, nearly bare skin extending from the medial canthus of each eye. They are lined by a combination of sebaceous and sudoriferous glands, and they produce secretions which contain pheromones and other semiochemical compounds. Ungulates frequently deposit these secretions on twigs and grass as a means of communication with other animals.

Self-anointing in animals, sometimes called anointing or anting, is a behaviour whereby a non-human animal smears odoriferous substances over themselves. These substances are often the secretions, parts, or entire bodies of other animals or plants. The animal may chew these substances and then spread the resulting saliva mixture over their body, or they may apply the source of the odour directly with an appendage, tool or by rubbing their body on the source.

Scent rubbing is a behavior where a mammal rubs its body against an object in their environment, sometimes in ones covered with strongly odored substances. It is typically shown in carnivores, although many mammals exhibit this behavior. Lowering shoulders, collapsing the forelegs, pushing forward and rubbing the chin, temples, neck, or back is how this act is performed. A variety of different odors can elicit this behavior including feces, vomit, fresh or decaying meat, insecticide, urine, repellent, ashes, human food and so on. Scent rubbing can be produced by an animal smelling novel odors, which include manufactured smells such as perfume or motor oil and carnivore smells including feces and food smells.

Wolves communicate using vocalizations, body postures, scent, touch, and taste. The lunar phases have no effect on wolf vocalisation. Despite popular belief, wolves do not howl at the Moon. Gray wolves howl to assemble the pack, usually before and after hunts, to pass on an alarm particularly at a den site, to locate each other during a storm or while crossing unfamiliar territory, and to communicate across great distances. Other vocalisations include growls, barks and whines. Wolves do not bark as loudly or continuously as dogs do but they bark a few times and then retreat from a perceived danger. Aggressive or self-assertive wolves are characterized by their slow and deliberate movements, high body posture and raised hackles, while submissive ones carry their bodies low, sleeken their fur, and lower their ears and tail. Raised leg urination is considered to be one of the most important forms of scent communication in the wolf, making up 60–80% of all scent marks observed.

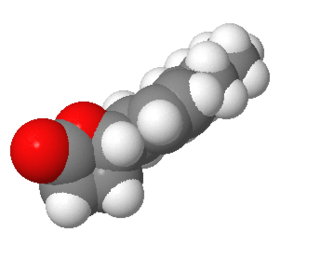

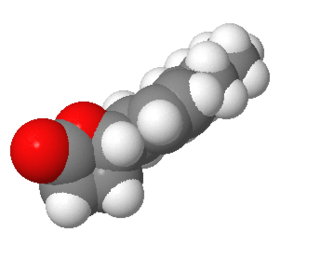

(Z)-6-Dodecen-4-olide is a volatile, unsaturated lipid and γ-lactone found in dairy products, and secreted as a pheromone by some even-toed ungulates. It has a creamy, cheesy, fatty flavour with slight floral undertones in small concentrations, but contributes towards the strong, musky smell of a few species of antelope and deer in higher concentrations.

Olfactic communication is a channel of nonverbal communication referring to the various ways people and animals communicate and engage in social interaction through their sense of smell. Our human olfactory sense is one of the most phylogenetically primitive and emotionally intimate of the five senses; the sensation of smell is thought to be the most matured and developed human sense.