A sphere is a geometrical object that is a three-dimensional analogue to a two-dimensional circle. A sphere is the set of points that are all at the same distance r from a given point in three-dimensional space. That given point is the centre of the sphere, and r is the sphere's radius. The earliest known mentions of spheres appear in the work of the ancient Greek mathematicians.

In geometry, the tangent line to a plane curve at a given point is the straight line that "just touches" the curve at that point. Leibniz defined it as the line through a pair of infinitely close points on the curve. More precisely, a straight line is said to be a tangent of a curve y = f(x) at a point x = c if the line passes through the point (c, f ) on the curve and has slope f'(c), where f' is the derivative of f. A similar definition applies to space curves and curves in n-dimensional Euclidean space.

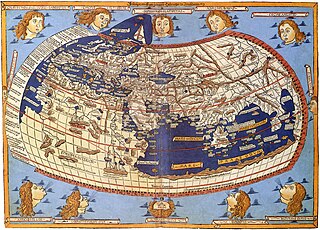

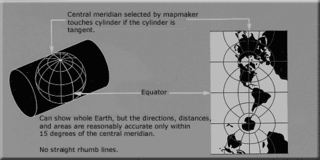

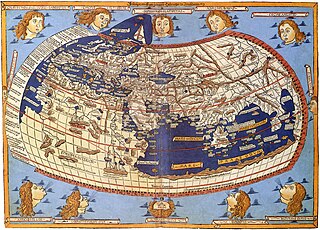

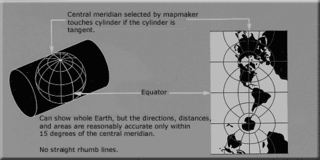

In cartography, map projection is the term used to describe a broad set of transformations employed to represent the two-dimensional curved surface of a globe on a plane. In a map projection, coordinates, often expressed as latitude and longitude, of locations from the surface of the globe are transformed to coordinates on a plane. Projection is a necessary step in creating a two-dimensional map and is one of the essential elements of cartography.

In mathematics, a stereographic projection is a perspective projection of the sphere, through a specific point on the sphere, onto a plane perpendicular to the diameter through the point. It is a smooth, bijective function from the entire sphere except the center of projection to the entire plane. It maps circles on the sphere to circles or lines on the plane, and is conformal, meaning that it preserves angles at which curves meet and thus locally approximately preserves shapes. It is neither isometric nor equiareal.

In geometry, a secant is a line that intersects a curve at a minimum of two distinct points. The word secant comes from the Latin word secare, meaning to cut. In the case of a circle, a secant intersects the circle at exactly two points. A chord is the line segment determined by the two points, that is, the interval on the secant whose ends are the two points.

In navigation, a rhumb line, rhumb, or loxodrome is an arc crossing all meridians of longitude at the same angle, that is, a path with constant bearing as measured relative to true north.

In geometry, inversive geometry is the study of inversion, a transformation of the Euclidean plane that maps circles or lines to other circles or lines and that preserves the angles between crossing curves. Many difficult problems in geometry become much more tractable when an inversion is applied. Inversion seems to have been discovered by a number of people contemporaneously, including Steiner (1824), Quetelet (1825), Bellavitis (1836), Stubbs and Ingram (1842-3) and Kelvin (1845).

The transverse Mercator map projection is an adaptation of the standard Mercator projection. The transverse version is widely used in national and international mapping systems around the world, including the Universal Transverse Mercator. When paired with a suitable geodetic datum, the transverse Mercator delivers high accuracy in zones less than a few degrees in east-west extent.

Orthographic projection in cartography has been used since antiquity. Like the stereographic projection and gnomonic projection, orthographic projection is a perspective projection in which the sphere is projected onto a tangent plane or secant plane. The point of perspective for the orthographic projection is at infinite distance. It depicts a hemisphere of the globe as it appears from outer space, where the horizon is a great circle. The shapes and areas are distorted, particularly near the edges.

A gnomonic map projection is a map projection which displays all great circles as straight lines, resulting in any straight line segment on a gnomonic map showing a geodesic, the shortest route between the segment's two endpoints. This is achieved by casting surface points of the sphere onto a tangent plane, each landing where a ray from the center of the sphere passes through the point on the surface and then on to the plane. No distortion occurs at the tangent point, but distortion increases rapidly away from it. Less than half of the sphere can be projected onto a finite map. Consequently, a rectilinear photographic lens, which is based on the gnomonic principle, cannot image more than 180 degrees.

In mathematics, a twisted cubic is a smooth, rational curve C of degree three in projective 3-space P3. It is a fundamental example of a skew curve. It is essentially unique, up to projective transformation. In algebraic geometry, the twisted cubic is a simple example of a projective variety that is not linear or a hypersurface, in fact not a complete intersection. It is the three-dimensional case of the rational normal curve, and is the image of a Veronese map of degree three on the projective line.

The scale of a map is the ratio of a distance on the map to the corresponding distance on the ground. This simple concept is complicated by the curvature of the Earth's surface, which forces scale to vary across a map. Because of this variation, the concept of scale becomes meaningful in two distinct ways.

The universal polar stereographic (UPS) coordinate system is used in conjunction with the universal transverse Mercator (UTM) coordinate system to locate positions on the surface of the earth. Like the UTM coordinate system, the UPS coordinate system uses a metric-based cartesian grid laid out on a conformally projected surface. UPS covers the Earth's polar regions, specifically the areas north of 84°N and south of 80°S, which are not covered by the UTM grids, plus an additional 30 minutes of latitude extending into UTM grid to provide some overlap between the two systems.

In geometry, a bitangent to a curve C is a line L that touches C in two distinct points P and Q and that has the same direction as C at these points. That is, L is a tangent line at P and at Q.

In mathematics, a developable surface is a smooth surface with zero Gaussian curvature. That is, it is a surface that can be flattened onto a plane without distortion. Conversely, it is a surface which can be made by transforming a plane. In three dimensions all developable surfaces are ruled surfaces. There are developable surfaces in four-dimensional space which are not ruled.

The Lambert azimuthal equal-area projection is a particular mapping from a sphere to a disk. It accurately represents area in all regions of the sphere, but it does not accurately represent angles. It is named for the Swiss mathematician Johann Heinrich Lambert, who announced it in 1772. "Zenithal" being synonymous with "azimuthal", the projection is also known as the Lambert zenithal equal-area projection.

In classical differential geometry, development refers to the simple idea of rolling one smooth surface over another in Euclidean space. For example, the tangent plane to a surface at a point can be rolled around the surface to obtain the tangent plane at other points.

In mathematics, the Riemannian connection on a surface or Riemannian 2-manifold refers to several intrinsic geometric structures discovered by Tullio Levi-Civita, Élie Cartan and Hermann Weyl in the early part of the twentieth century: parallel transport, covariant derivative and connection form. These concepts were put in their current form with principal bundles only in the 1950s. The classical nineteenth century approach to the differential geometry of surfaces, due in large part to Carl Friedrich Gauss, has been reworked in this modern framework, which provides the natural setting for the classical theory of the moving frame as well as the Riemannian geometry of higher-dimensional Riemannian manifolds. This account is intended as an introduction to the theory of connections.

The terminology of algebraic geometry changed drastically during the twentieth century, with the introduction of the general methods, initiated by David Hilbert and the Italian school of algebraic geometry in the beginning of the century, and later formalized by André Weil, Jean-Pierre Serre and Alexander Grothendieck. Much of the classical terminology, mainly based on case study, was simply abandoned, with the result that books and papers written before this time can be hard to read. This article lists some of this classical terminology, and describes some of the changes in conventions.

The Gall stereographic projection, presented by James Gall in 1855, is a cylindrical projection. It is neither equal-area nor conformal but instead tries to balance the distortion inherent in any projection.