Individualism is the moral stance, political philosophy, ideology, and social outlook that emphasizes the intrinsic worth of the individual. Individualists promote realizing one's goals and desires, valuing independence and self-reliance, and advocating that the interests of the individual should gain precedence over the state or a social group, while opposing external interference upon one's own interests by society or institutions such as the government. Individualism makes the individual its focus, and so starts "with the fundamental premise that the human individual is of primary importance in the struggle for liberation".

Sociology of religion is the study of the beliefs, practices and organizational forms of religion using the tools and methods of the discipline of sociology. This objective investigation may include the use both of quantitative methods and of qualitative approaches.

Communitarianism is a philosophy that emphasizes the connection between the individual and the community. Its overriding philosophy is based on the belief that a person's social identity and personality are largely molded by community relationships, with a smaller degree of development being placed on individualism. Although the community might be a family, communitarianism usually is understood, in the wider, philosophical sense, as a collection of interactions, among a community of people in a given place, or among a community who share an interest or who share a history. Communitarianism is often contrasted with individualism, and opposes laissez-faire policies that deprioritize the stability of the overall community.

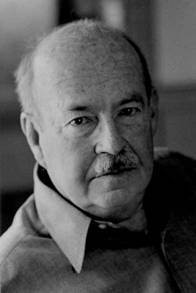

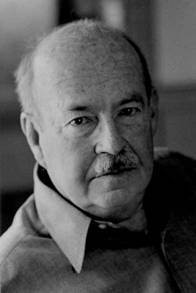

Talcott Parsons was an American sociologist of the classical tradition, best known for his social action theory and structural functionalism. Parsons is considered one of the most influential figures in sociology in the 20th century. After earning a PhD in economics, he served on the faculty at Harvard University from 1927 to 1973. In 1930, he was among the first professors in its new sociology department. Later, he was instrumental in the establishment of the Department of Social Relations at Harvard.

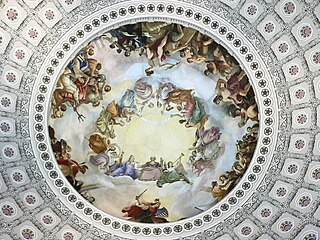

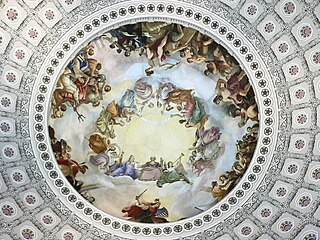

Civil religion, also referred to as a civic religion, is the implicit religious values of a nation, as expressed through public rituals, symbols, and ceremonies on sacred days and at sacred places. It is distinct from churches, although church officials and ceremonies are sometimes incorporated into the practice of civil religion. Countries described as having a civil religion include France and the United States. As a concept, it originated in French political thought and became a major topic for U.S. sociologists since its use by Robert Bellah in 1960.

Jewish atheism is the atheism of people who are ethnically and culturally Jewish.

In the history of colonialism, a plantation was a form of colonization in which settlers would establish permanent or semi-permanent colonial settlements in a new region. The term first appeared in the 1580s in the English language to describe the process of colonization before being also used to refer to a colony by the 1610s. By the 1710s, the word was also being used to describe large farms where cash crop goods were produced, typically in tropical regions.

Robert Neelly Bellah was an American sociologist and the Elliott Professor of Sociology at the University of California, Berkeley. He was internationally known for his work related to the sociology of religion.

Robert John Wuthnow is an American sociologist who is widely known for his work in the sociology of religion. He is the Gerhard R. Andlinger Professor of Sociology Emeritus at Princeton University, where he is also the former chair of the Department of Sociology and director of the Princeton University Center for the Study of Religion.

American civil religion is a sociological theory that a monotheistic nonsectarian civil religion exists within the United States with sacred symbols drawn from national history. Scholars have portrayed it as a common set of values that foster social and cultural integration. The ritualistic elements of ceremonial deism found in American ceremonies and presidential invocations of God can be seen as expressions of the American civil religion.

Lifestyle enclave is a sociological term first used by Robert N. Bellah et al. in their 1985 book, Habits of the Heart: Individualism and Commitment in American Life. In the glossary of the book, they provide the following definition: "A lifestyle enclave is formed by people who share some feature of private life. Members of a lifestyle enclave express their identity through shared patterns of appearance, consumption, and leisure activities, which often serve to differentiate them sharply from those with other lifestyles." This term is contrasted with community, which Bellah et al. claim is characterized by social interdependence, shared history, and shared participation in politics.

Face negotiation theory is a theory conceived by Stella Ting-Toomey in 1985, to understand how people from different cultures manage rapport and disagreements. The theory posited "face", or self-image when communicating with others, as a universal phenomenon that pervades across cultures. In conflicts, one's face is threatened; and thus the person tends to save or restore his or her face. This set of communicative behaviors, according to the theory, is called "facework". Since people frame the situated meaning of "face" and enact "facework" differently from one culture to the next, the theory poses a cross-cultural framework to examine facework negotiation. It is important to note that the definition of face varies depending on the people and their culture and the same can be said for the proficiency of facework. According to Ting-Toomey's theory, most cultural differences can be divided by Eastern and Western cultures, and her theory accounts for these differences.

Religious economy refers to religious persons and organizations interacting within a market framework of competing groups and ideologies. An economy makes it possible for religious suppliers to meet the demands of different religious consumers. By offering an array of religions and religious products, a competitive religious economy stimulates such activity in a market-type setting.

"Spiritual but not religious" (SBNR), also known as "spiritual but not affiliated" (SBNA), or less commonly "more spiritual than religious" is a popular phrase and initialism used to self-identify a life stance of spirituality that does not regard organized religion as the sole or most valuable means of furthering spiritual growth. Historically, the words religious and spiritual have been used synonymously to describe all the various aspects of the concept of religion, but in contemporary usage spirituality has often become associated with the interior life of the individual, placing an emphasis upon the well-being of the "mind-body-spirit", while religion refers to organizational or communal dimensions. Spirituality sometimes denotes noninstitutionalized or individualized religiosity. The interactions are complex since even conservative Christians designate themselves as "spiritual but not religious" to indicate a form of non-ritualistic personal faith.

Postmodern religion is any type of religion that is influenced by postmodernism and postmodern philosophies. Examples of religions that may be interpreted using postmodern philosophy include Postmodern Christianity, Postmodern Neopaganism, and Postmodern Buddhism. Postmodern religion is not an attempt to banish religion from the public sphere; rather, it is a philosophical approach to religion that critically considers orthodox assumptions. Postmodern religious systems of thought view realities as plural, subjective, and dependent on the individual's worldview. Postmodern interpretations of religion acknowledge and value a multiplicity of diverse interpretations of truth, being, and ways of seeing. There is a rejection of sharp distinctions and global or dominant metanarratives in postmodern religion, and this reflects one of the core principles of postmodern philosophy. A postmodern interpretation of religion emphasises the key point that religious truth is highly individualistic, subjective, and resides within the individual.

Pragmatic ethics is a theory of normative philosophical ethics and meta-ethics. Ethical pragmatists such as John Dewey believe that some societies have progressed morally in much the way they have attained progress in science. Scientists can pursue inquiry into the truth of a hypothesis and accept the hypothesis, in the sense that they act as though the hypothesis were true; nonetheless, they think that future generations can advance science, and thus future generations can refine or replace their accepted hypotheses. Similarly, ethical pragmatists think that norms, principles, and moral criteria are likely to be improved as a result of inquiry.

Settler society is a theoretical term in the early modern period and modern history that describes a common link between modern, predominantly European, attempts to permanently settle in other areas of the world. It is used to distinguish settler colonies from resource extraction colonies. The term came to wide use in the 1970s as part of the discourse on decolonization, particularly to describe older colonial units.

Cultural differences can interact with positive psychology to create great variation, potentially impacting positive psychology interventions. Culture differences have an impact on the interventions of positive psychology. Culture influences how people seek psychological help, their definitions of social structure, and coping strategies. Cross cultural positive psychology is the application of the main themes of positive psychology from cross-cultural or multicultural perspectives.

Ann Swidler is an American sociologist and professor of sociology at the University of California, Berkeley. Swidler is most commonly known as a cultural sociologist and authored one of the most-cited articles in sociology, "Culture in Action: Symbols and Strategies".

Richard Madsen is an American sociologist. He is currently distinguished professor of sociology the University of California, San Diego, specializing in sociology of China.