Maharao Shekhaji (1433–1488) was a Rajput ruler in 15th-century India. He is the namesake of the Shekhawati region, comprising the districts of Sikar, Churu and Jhunjhunu in the modern Indian state of Rajasthan. His descendants are known as the Shekhawat.

Sikar is a city and municipal council in the Sikar district of the state of Rajasthan in India. It is the administrative headquarters of the Sikar district. It is largest city of the Shekhawati region, which consists of Sikar, Churu and Jhunjhunu. After Kota, Sikar is one of the major hubs for private coaching in the country for competitive public examination preparations and has a number of engineering and medical coaching institutes.

Shekhawati is a semi-arid historical region located in the northeast part of Rajasthan, India. The region was ruled by Shekhawat Rajputs. Shekhawati is located in North Rajasthan, comprising the districts of Neem Ka Thana, Jhunjhunu, Sikar that lies to the west of the Aravalis and Churu. It is bounded on the northwest by the Bagar region, on the northeast by Haryana, on the east by Mewat, on the southeast by Dhundhar, on the south by Ajmer, and on the southwest by the Marwar region. Its area is 13,784 square kilometers.

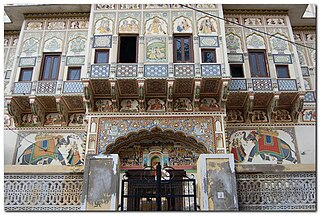

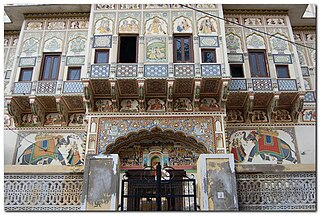

Ratangarh is a town and Tehsil of the Churu district in Rajasthan, India. Ratangarh was previously called Kolasar. It is famous for grand havelis (mansions) with frescoes, which is an architectural specialty of the Shekhawati region. Ratangarh is also famous for its handicraft work.

Fatehpur is a city in the Sikar district of Indian state Rajasthan. It is part of the Shekhawati region. It is midway between Sikar city and Bikaner on National Highway 52. It is also the land to Havelis built by Marwari Seth's. It also has many Kuldevi Temples of the Agarwal community for Bajoria,Bindal, Saraf, Chamadia, Choudhary, Goenka, Lohia, Singhania, Saraogi, Bhartia Families. It is famous for its extreme weather conditions throughout the year. In winters, the minimum temperature falls below 0 °C at night. In summer the temperature rises to 50 °C in the afternoon making it one of the hottest places in India. 1985 Bollywood film Ghulami starting Dharmendra, Naseeruddin Shah, Mithun Chakraborty and Smita Patil was extensively shot here in many of its havelis and the railway station.

Nawalgarh is a heritage city in Jhunjhunu district of Indian state of Rajasthan. It is part of the Shekhawati region and is midway between Jhunjhunu and Sikar. It is 31.5 km from Sikar and 39.2 km from Jhunjhunu. Nawalgarh is famous for its fresco and havelis and considered as Golden City of Rajasthan. It is also the motherland of some great business families of India.

Chhatri are semi-open, elevated, dome-shaped pavilions used as an element in Indo-Islamic architecture and Indian architecture. They are most commonly square, octagonal, and round.

Shekhawat is a clan of Rajputs found mainly in Shekhawati region of Rajasthan. Shekhawats are descendants of Maharao Shekha of Amarsar. The Shekhawat Rajputs trace their lineage to Shekha Rao, a prominent Rajput chieftain from the 15th century. Shekha Rao was a descendant of Rao Kalyan Singh, who belonged to the Kachwaha Rajput clan. Rao Shekha established his own principality in the Shekhawati region of Rajasthan, which includes parts of present-day Jhunjhunu, Sikar, and Churu districts. His leadership helped consolidate Rajput power in this region. Over time, the Shekhawat Rajputs expanded their territories and established several forts and palaces. The Shekhawat Rajputs established their dominance in the Shekhawati region in the 15th century, specifically starting around the time of Shekha Rao's rise to prominence in the early 1400s. They played a significant role in regional politics and were known for their martial prowess and resistance against Mughal expansion. Their rule continued until the mid-20th century when the princely states were integrated into the Indian Union. Thus, the Shekhawat Rajputs governed the Shekhawati region for approximately 500 years, from the early 15th century until the 1940s and 1950s, when princely states were absorbed into independent India. Shekhawat is a very common surname in the Indian defence forces.

Mandawa is a town, just 29 km from Jhunjhunu city in Jhunjhunu district of Rajasthan, India. It is part of Shekhawati region. Mandawa is located at 28.05°N 75.15°E. It has an average elevation of 316 metres (1036 ft). The nearest railway station is Jhunjhunu railway station.

Jhunjhunu district is a district of the Indian state of Rajasthan in northern India. The city of Jhunjhunu is the district headquarters. Jhunjhunu is an old and historical town having its own district headquarters. It is said that it was ruled over by Chouhan dynasty in the Vikram era 1045. The district is famous for the frescos on its grand Havelis. It is also famous for providing considerable representation to Indian defense forces. Jhunjhunu district was named in the memory of a Jat named "Jhunjha" or "Jujhar Singh Nehra". The district has a population of 2,139,658, an area of 5926 km2, and a population density of 361 persons per km. The district falls within Shekhawati region, and is bounded on the North-East and East by Haryana state, on the South-East, South & South-West by Sikar District & on the North-West and North by Churu District.

Sikar district is a district of the Indian state Rajasthan in northern India. It is a part of the Shekhawati region of Rajasthan. Rao Daulat Singh laid down the foundation stone of Thikana Sikar in 1687. District Collector of Sikar is Shri Mukul Sharma while Member of Parliament is Shri Amra Ram.

Mahansar is a village in the Shekhawati region in Rajasthan, India. It was founded in 1768 by the Thakurs of one of the branch of Shekhawats. It is located in Jhunjhunu District at a distance of 40 km from Jhunjhunu near the trifurcation of Jhunjhunu, Churu and Sikar districts.

Chhapar is a small town and a municipality in Churu district in the state of Rajasthan, India. Chhapar and Tal chhapar is located in the Churu district of Northwestern Rajasthan in the Shekhawati region of India. It is 210 km from Jaipur and situated on the road from Ratangarh to Sujangarh. The Tal Chappar lies in the Sujangarh Tehsil of Churu district. It lies on the Nokha-Sujangarh state highway and is situated at a distance of 85 km from Churu and about 132 km from Bikaner. The nearest railway station is Chappar which lies on Degana-Churu-Rewari broad gauge line of Northern Western Railways. The nearest Airport is Jaipur International Airport (Sanganer) which is at a distance of 215 km from Chappar. It is known for black bucks but it is also home to a variety of birds. Here is a famous sanctuary known as Tal Chhapar Sanctuary

Ramgarh or Ramgarh Shekhawati is a town and a municipality in Ramgarh tehsil of Sikar district in the Indian state of Rajasthan.

Nangal Sirohi, famous for the painted Shekhavati Rajput architecture Havelis, is a village in Mahendragarh district in the Indian state of Haryana. It is 9.5 km from Mahendragarh towards Narnaul in South Haryana.

Tain is a village in the Jhunjhunu district, India. It is part of the Shekhawati region of Rajasthan.

Kalipahari village is a big community of Shekhawat Rajputs in the Jhunjhunu District of Rajasthan. It is situated 5 km south of Bagar, Jhunjhunu. The village is famous for the frescos on its grand havelis.

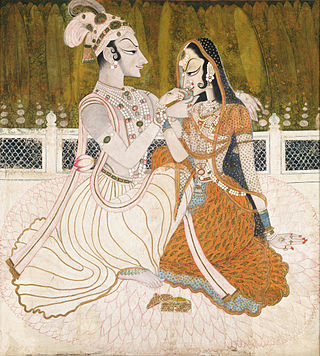

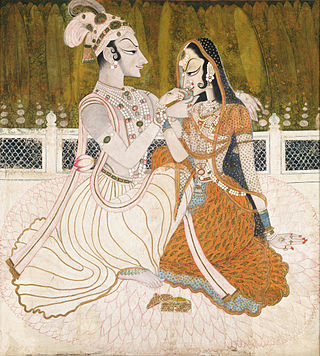

Apart from the architecture of Rajasthan, the most notable forms of the visual art of Rajasthan are architectural sculpture on Hindu and Jain temples in the medieval era, in painting illustrations to religious texts, beginning in the late medieval period, and post-Mughal miniature painting in the Early Modern period, where various different court schools developed, together known as Rajput painting. In both cases, Rajasthani art had many similarities to that of the neighbouring region of Gujarat, the two forming most of the region of "Western India", where artistic styles often developed together.

Khetri Mahal, also known as the Wind Palace, whose ruins are an example of palace architecture in the Indian state of Rajasthan.

The Bikaner–Rewari line or Rewari–Bikaner line is a railway route on the North Western Railway zone of Indian Railways. This route plays an important role in rail transportation of Bikaner division and Jaipur division of Rajasthan state and Gurugram division of Haryana state.