Tilbury Fort, also known historically as the Thermitage Bulwark and the West Tilbury Blockhouse, is an artillery fort on the north bank of the River Thames in England. The earliest version of the fort, comprising a small blockhouse with artillery covering the river, was constructed by King Henry VIII to protect London against attack from France as part of his Device programme. It was reinforced during the 1588 Spanish Armada invasion scare, after which it was reinforced with earthwork bastion, and Parliamentary forces used it to help secure the capital during the English Civil War of the 1640s. Following naval raids during the Anglo-Dutch Wars, the fort was enlarged by Sir Bernard de Gomme from 1670 onwards to form a star-shaped defensive work, with angular bastions, water-filled moats and two lines of guns facing onto the river.

The Western Heights of Dover are one of the most impressive fortifications in Britain. They comprise a series of forts, strong points and ditches, designed to protect the country from invasion. They were created in the 18th and 19th centuries to augment the existing defences and protect the key port of Dover from both seaward and landward attack; by the start of the 20th century Dover Western Heights was collectively reputed to be the 'strongest and most elaborate' fortification in the country. The Army finally withdrew from the Heights in 1956–61; they are now a local nature reserve.

Grain Fort is a former artillery fort located just east of the village of Grain, Kent. It was constructed in the 1860s to defend the confluence of the Rivers Medway and Thames during a period of tension with France. The fort's location enabled its guns to support the nearby Grain Tower and Garrison Point Fort at Sheerness on the other side of the Medway. It was repeatedly altered and its guns upgraded at various points in its history, before being decommissioned in 1956 when the UK abolished its coastal defence programme. It was subsequently demolished. The remnants of the fort are still visible and have been incorporated into a coastal park.

Garrison Point Fort is a former artillery fort situated at the end of the Garrison Point peninsula at Sheerness on the Isle of Sheppey in Kent. Built in the 1860s in response to concerns about a possible French invasion, it was the last in a series of artillery batteries that had existed on the site since the mid-16th century. The fort's position enabled it to guard the strategic point where the River Medway meets the Thames. It is a rare example of a two-tiered casemated fort – one of only two of that era in the country – with a design that is otherwise similar to that of several of the other forts along the lower Thames. It remained operational until 1956 and is now used by the Sheerness Docks as a port installation.

Slough Fort is a small artillery fort that was built at Allhallows-on-Sea in the north of the Hoo Peninsula in Kent. Constructed in 1867, the D-shaped fort was intended to guard a vulnerable stretch of the River Thames against possible enemy landings during a period of tension with France. Its seven casemates initially accommodated rifled breech loading guns, which were replaced by the turn of the century by more powerful breech-loaders on disappearing carriages, mounted in concrete wing batteries on either side of the fort. It was likely one of the smallest of the forts constructed as a result of the 1860s invasion scare.

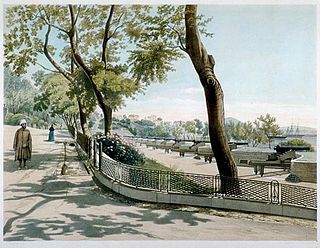

New Tavern Fort is an historic artillery fort in Gravesend, Kent. Dating mostly from the 18th and 19th centuries, it is an unusually well-preserved example of an 18th-century fortification and remained in use for defensive purposes until the Second World War. It was built during the American War of Independence to guard the Thames against French and Spanish raiders operating in support of the newly formed United States of America. It was redesigned and rebuilt in the mid-19th century to defend against a new generation of iron-clad French warships.

Coalhouse Fort is an artillery fort in the eastern English county of Essex. It was built in the 1860s to guard the lower Thames from seaborne attack. It stands at Coalhouse Point on the north bank of the river, at a location near East Tilbury which was vulnerable to raiders and invaders. It was the last in a series of fortifications dating back to the 15th century and was the direct successor to a smaller mid-19th century fort built on the same site. Constructed during a period of tension with France, its location on marshy ground caused problems from the start and led to a lengthy construction process. The fort was equipped with a variety of large-calibre artillery guns and the most modern defensive facilities of the time, including shell-proof casemates protected by granite facing and cast-iron shields. Its lengthy construction and the rapid pace of artillery development at the time meant that it was practically obsolete for its original purpose within a few years of its completion.

Harwich Redoubt is a circular fort built in 1808 to defend the port of Harwich, Essex from Napoleonic invasion. The Harwich Society opens it to the public.

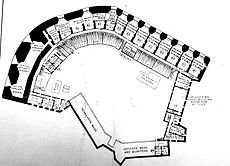

Fort Gilkicker is a historic Palmerston fort built at the eastern end of Stokes Bay, Gosport, Hampshire England to dominate the key anchorage of Spithead. It was erected between 1863 and 1871 as a semi-circular arc with 22 casemates, to be armed with five twelve-inch guns, seventeen ten-inch guns and five nine-inch guns. The actual installed armament rather differed from this. In 1902 the RML guns were replaced by two 9.2-inch and two six-inch BL guns, and before the First World War the walls were further strengthened with substantial earthwork embankments. The fort was disarmed in 1956 and used for storage until 1999, and is currently in a state of disrepair.

Fort Fareham is one of the Palmerston Forts, in Fareham, England. After the Gosport Advanced Line of Fort Brockhurst, Fort Elson, Fort Rowner, Fort Grange and Fort Gomer had been approved by the Royal Commission on the Defence of the United Kingdom a decision was made to build an outer line of three more forts two miles in advance of the Gosport Advanced Line. Of these three projected forts only Fort Fareham was built due to the need to cut costs. It acted as a hinge between the forts on Portsdown Hill and those of the Gosport Advanced Line, filling the gap at Fareham. It has been a Grade II Listed Building since 1976.

Fort Nelson, in the civil parish of Boarhunt in the English county of Hampshire, is one of five defensive forts built on the summit of Portsdown Hill in the 1860s, overlooking the important naval base of Portsmouth. It is now part of the Royal Armouries, housing their collection of artillery, and a Grade I Listed Building.

Cliffe Fort is a disused artillery fort built in the 1860s to guard the entrance to the Thames from seaborne attack. Constructed during a period of tension with France, it stands on the south bank of the river at the entrance to Cliffe Creek in the Cliffe marshes on the Hoo Peninsula in North Kent, England. Its location on marshy ground caused problems from the start and necessitated changes to its design after the structure begin to crack and subside during construction. The fort was equipped with a variety of large-calibre artillery guns which were intended to support two other nearby Thamesside forts. A launcher for the Brennan torpedo—which has been described as the world's first practical guided missile—was installed there at the end of the 19th century but was only in active use for a few years.

Fort Ballance is a former coastal artillery battery on Point Gordon on Wellington's Miramar Peninsula.

Grain Tower is a mid-19th-century gun tower situated offshore just east of Grain, Kent, standing in the mouth of the River Medway. It was built along the same lines as the Martello towers that were constructed along the British and Irish coastlines in the early 19th century and is the last-built example of a gun tower of this type. It owed its existence to the need to protect the important dockyards at Sheerness and Chatham from a perceived French naval threat during a period of tension in the 1850s.

Buena Vista Battery was an artillery battery near the Buena Vista Barracks at the southern end of the British Overseas Territory of Gibraltar. It is located on a slight ridge in front of the nearby Buena Vista Barracks, which was once the base of the Royal Gibraltar Regiment.

Victoria Battery was an artillery battery in the British Overseas Territory of Gibraltar. It was built in the 1840s on top of the earlier Princess of Wales Batteries following a report by Major-General Sir John Thomas Jones on Gibraltar's defences. The battery was located on the west side of Gibraltar and was one of a number of "retired" batteries in the territory, constructed to improve the coastal defences between Europa Point and the town.

The Twydall Profile was a style of fortification used in British and Imperial polygonal forts at the end of the 19th century. The sloping earthworks employed in the Twydall Profile were intended to be quick and inexpensive to construct and to be effective in the face of the more powerful artillery and high explosive ammunition being introduced at that time. The name comes from the village of Twydall in Kent, where the first forts of this type were built.

Fort Davis, is a coastal defence fortification close to Whitegate, County Cork, Ireland. Together with similar structures at Fort Mitchel, Fort Camden (Crosshaven), and Templebreedy Battery, the fort was built to defend the mouth of Cork Harbour. Though used as a fortification from the early 17th century, the current structures of the 74-acre site date primarily from the 1860s. Originally named Fort Carlisle and operated by the British Armed Forces, the fort was handed-over to the Irish Defence Forces in 1938, and renamed Fort Davis. The facility is owned by the Department of Defence, and is used as a military training site with no public access.

Tarġa Battery is an artillery battery on the boundary between St. Paul's Bay and Mosta, Malta. It was built in 1887 by the British as part of the Victoria Lines. The battery is now in the hands of the Mosta Local Council, who intend to restore it and open it to the public.

Point Battery is a former gun emplacement on Portsmouth Point in Hampshire. Part of the fortifications of Portsmouth, it was built alongside an earlier defensive structure to help defend Portsmouth Harbour in the event of an attack. Fort Blockhouse on the other side of the harbour entrance was rebuilt at around the same time as part of the same scheme. In the mid-19th century the battery was enlarged and Point Barracks were built alongside, to house the artillery troops responsible for manning the defences.