Related Research Articles

State Shintō was Imperial Japan's ideological use of the Japanese folk religion and traditions of Shinto. The state exercised control of shrine finances and training regimes for priests to strongly encourage Shinto practices that emphasized the Emperor as a divine being.

An ōnusa or simply nusa or Taima is a wooden wand traditionally used in Shinto purification rituals.

A kannushi, also called shinshoku, is a person responsible for the maintenance of a Shinto shrine as well as for leading worship of a given kami. The characters for kannushi are sometimes also read as jinshu with the same meaning.

The Association of Shinto Shrines is a religious administrative organisation that oversees about 80,000 Shinto shrines in Japan. These shrines take the Ise Grand Shrine as the foundation of their belief. It is the largest Shrine Shinto organization in existence.

A Gokoku Shrine is a shrine dedicated to the spirit of those who died for the nation. They were renamed from Shōkonsha (招魂社) in 1939. Before World War II, they were under the jurisdiction of the Ministry of the Interior, but after World War II they are administered by an independent religious corporation. Designated Gokoku Shrines were built in prefectures except Tokyo and Kanagawa Prefecture. The main deities are war dead from the prefecture or those who are related to them, as well as self-defense officers, police officers, firefighters, and others killed in the line of duty.

Ubusunagami in Shinto are tutelary kami of one's birthplace.

Chokusaisha (勅祭社) is a shrine where an imperial envoy Chokushi (勅使) performs rituals: chokushi sankō no jinja (勅使参向の神社). The following table shows sixteen shrines designated as Chokusaisha.

Oharae no Kotoba (大祓のことば) is one of the Noritos in Shinto rituals. It is also called Nakatomi Saimon, Nakatomi Exorcism Words, or Nakatomi Exorcism for short, because it was originally used in the Ōharae-shiki ceremony and the Nakatomi clan was solely responsible for reading it. A typical example can be found in Enki-Shiki, Volume 8, under the title June New Year's Eve Exorcism. In general, the term "Daihourishi" refers to the words to be proclaimed to the participants of the event, while the term "Nakatomihourai" refers to a modified version of the words to be performed before the shrine or gods.

Toyama Gokoku Shrine is a Shinto shrine located in Toyama, Toyama Prefecture, Japan. It enshrines the kami of "martyrs of the state" (国事殉難者) or soldiers whom have perished and its annual festivals take place on April 25 and October 5. It was established in 1913. In total, there are 28,679 people enshrined.

Secular Shrine Theory or Jinja hishūkyōron (神社非宗教論) was a religious policy and political theory that arose in Japan during the 19th and early 20th centuries due to the separation of church and state of the Meiji Government. It was the idea that Shinto Shrines were secular in their nature rather than religious, and that Shinto was not a religion, but rather a secular set of Japanese national traditions. This was linked to State Shinto and the idea that the state controlling and enforcing Shinto was not a violation of freedom of religion. It was subject to immense debate over this time and ultimately declined and disappeared during the Shōwa era.

Shinto is a religion native to Japan with a centuries'-long history tied to various influences in origin.

Chinjugami is a god enshrined to protect a specific building or a certain area of land. Nowadays, it is often equated with Ujigami and Ubusunagami. A shrine that enshrines a guardian deity is called a Chinjusha.

Sect Shinto refers to several independent organized Shinto groups that were excluded by law in 1882 from government-run State Shinto. These independent groups have more developed belief systems than mainstream Shrine Shinto, which focuses more on rituals. Many such groups are organized into the Kyōha Shintō Rengōkai. Before World War II, Sect Shinto consisted of 13 denominations, which were referred to as the 13 Shinto schools. Since then, there have been additions and withdrawals of membership.

The term unity of religion and rule refers to the unification of ritual and politics. ritual in ritual-politics means "ritual" and religion. The word "politics" means "ritual" and politics.

The Office of Japanese Classics Research was a central government organization for the training of the Shinto priesthood in Japan. It was established by the Meiji Government in 1882 as the successor organization to the Bureau of Shinto Affairs. Prince Arisugawa Takahito was its first leader.

Shinto Taiseikyo (神道大成教) is one of the thirteen Shinto sects. It was founded by Hirayama Seisai (1815–1890) and is considered a form of Confucian Shinto.

Jingūkyō (神宮教) is a sect of Shinto that originated from Ise Grand Shrine, the Ise faith. It was not technically a Sect Shinto group but had characteristics of one. It was founded in 1882, and was reorganized into the Jingū Service Foundation in 1899.

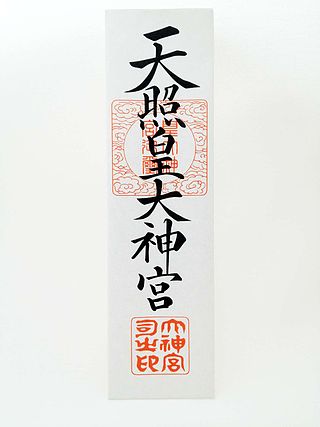

Jingū Taima is an ōnusa wrapped in clean Ise washi and issued by the Ise Grand Shrine. They are a form of ofuda. The Association of Shinto Shrines recommends every household have at least three Ofuda in their Kamidana, a Jingu Taima, an Ujigami ofuda, and another deity one personally chooses.

The Bureau of Shrines was an internal department of the Ministry of the Interior that existed until 1940. It was in charge of administrative matters related to shrines, Shinkan, and Kannushi.

The Great Teaching Institute was an organization under the Ministry of Religion in the Empire of Japan.

References

- 1 2 "Basic Terms of Shinto: J". www2.kokugakuin.ac.jp. Retrieved 2023-03-10.

- ↑ 景山春樹 「神道」『世界大百科事典』 219頁。

- ↑ 「宗教特別専攻」,『国学院大学 令和2年(2020)入学試験要項』2019,p.8(2021.8.30閲覧)。

- ↑ 神職後継者専攻:神社系教団用,『皇學館大学受験生サイトCampus Vew』,出願書類のダウンロード>AO入試神職後継専攻のみ(2021.8.30閲覧).

- ↑ Kogakkan University Faculty of Letters: Kogakkan University official website

- ↑ S.D.B.Picken "Faith-based schools in Japan: Paradoxes and Pointers". In J.D. Chapman et al. (eds.) "International Handbook of Learning, Teaching and Leading in Faith-Based Schools". New York: Springer. P. 523.

- ↑ 大阪府神社庁 第六支部 東大阪市

- ↑ 『平成29年版 宗教年鑑』参照

- ↑ 文部省・学制百年史編集委員会「明治初期における宗教行政」 、『学制百年史』(1972年)「編集後記」。

- ↑ 武田政一 「神社」『世界大百科事典』 118頁。

- ↑ 『日本キリスト教会50年史』62頁。

- ↑ 加藤玄智(陸軍士官学校教授・東京帝国大学神道講座助教授)は1924年(大正13年)の著書『東西思想比較研究』以降、この説を展開した。