Related Research Articles

The People's Army of Vietnam, also recognized as the Vietnam People's Army (VPA) or the Vietnamese Army, is the military force of the Socialist Republic of Vietnam and the armed wing of the ruling Communist Party of Vietnam. The PAVN is a part of the Vietnam People's Armed Forces and includes: Ground Force, Navy, Air Defence - Air Force and Border Guard. However, Vietnam does not have a separate Ground Force or Army branch. All ground troops, army corps, military districts and specialised arms belong to the Ministry of Defence, directly under the command of the Central Military Commission, the Minister of Defence, and the General Staff of the Vietnam People's Army. The military flag of the PAVN is the flag of the Socialist Republic of Vietnam, with the words Quyết thắng added in yellow at the top left.

The Vietnam War was a conflict in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia from 1 November 1955 to the fall of Saigon on 30 April 1975. It was the second of the Indochina Wars and was officially fought between North Vietnam and South Vietnam. North Vietnam was supported by the Soviet Union, China, and other communist allies; South Vietnam was supported by the United States and other anti-communist allies. The war is widely considered to be a Cold War-era proxy war. It lasted almost 20 years, with direct U.S. involvement ending in 1973. The conflict also spilled over into neighboring states, exacerbating the Laotian Civil War and the Cambodian Civil War, which ended with all three countries becoming communist states by 1975.

The Viet Cong was an armed communist revolutionary organization in South Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia. It fought under the direction of North Vietnam, against the South Vietnamese and United States governments during the Vietnam War, eventually emerging on the winning side. It had both guerrilla and regular army units, as well as a network of cadres who organized peasants in the territory the Viet Cong controlled. During the war, communist fighters and anti-war activists claimed that the Viet Cong was an insurgency indigenous to the South, while the U.S. and South Vietnamese governments portrayed the group as a tool of North Vietnam. According to Trần Văn Trà, the Viet Cong's top commander, and the post-war Vietnamese government's official history, the Viet Cong followed orders from Hanoi and were part of the People's Army of Vietnam, or North Vietnamese army.

Melvin Robert Laird Jr. was an American politician, writer and statesman. He was a U.S. congressman from Wisconsin from 1953 to 1969 before serving as Secretary of Defense from 1969 to 1973 under President Richard Nixon. Laird was instrumental in forming the administration's policy of withdrawing U.S. soldiers from the Vietnam War; he coined the expression "Vietnamization," referring to the process of transferring more responsibility for combat to the South Vietnamese forces. First elected in 1952, Laird was the last surviving Representative elected to the 83rd Congress at the time of his death.

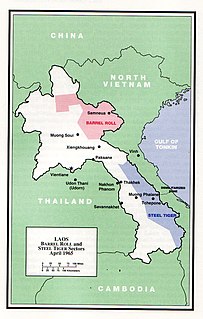

The Laotian Civil War (1959–1975) was a civil war in Laos which was waged between the Communist Pathet Lao and the Royal Lao Government from 23 May 1959 to 2 December 1975. It is associated with the Cambodian Civil War and the Vietnam War, with both sides receiving heavy external support in a proxy war between the global Cold War superpowers. It is called the Secret War among the American CIA Special Activities Center, and Hmong and Mien veterans of the conflict.

The Cambodian Civil War was a civil war in Cambodia fought between the forces of the Communist Party of Kampuchea against the government forces of the Kingdom of Cambodia and, after October 1970, the Khmer Republic, which had succeeded the kingdom.

Military Assistance Command, Vietnam – Studies and Observations Group (MACV-SOG) was a highly classified, multi-service United States special operations unit which conducted covert unconventional warfare operations prior to and during the Vietnam War.

Operation Steel Tiger was a covert U.S. 2nd Air Division, later Seventh Air Force and U.S. Navy Task Force 77 aerial interdiction effort targeted against the infiltration of People's Army of Vietnam (PAVN) men and material moving south from the Democratic Republic of Vietnam through southeastern Laos to support their military effort in the Republic of Vietnam during the Vietnam War.

CIA activities in Vietnam were operations conducted by the Central Intelligence Agency in Vietnam from the 1950s to the late 1960s, before and during the Vietnam War. After the 1954 Geneva Conference, North Vietnam was controlled by communist forces under Ho Chi Minh's leadership. South Vietnam, with the assistance of the U.S., was anti-communist. The economic and military aid supplied by the U.S. to South Vietnam continued until the 1970s. The CIA participated in both the political and military aspect of the wars in Indochina. The CIA provided suggestions for political platforms, supported candidates, used agency resources to refute electoral fraud charges, manipulated the certification of election results by the South Vietnamese National Assembly, and instituted the Phoenix Program. It worked particularly closely with the ethnic minority Montagnards, Hmong, and Khmer. There are 174 National Intelligence Estimates dealing with Vietnam, issued by the CIA after coordination with the US intelligence community.

The 1959 to 1963 phase of the Vietnam War started after the North Vietnamese had made a firm decision to commit to a military intervention in the guerrilla war in the South Vietnam, a buildup phase began, between the 1959 North Vietnamese decision and the Gulf of Tonkin Incident, which led to a major US escalation of its involvement. Vietnamese communists saw this as a second phase of their revolution, the US now substituting for the French.

During the Cold War in the 1960s, the United States and South Vietnam began a period of gradual escalation and direct intervention referred to as the joint warfare in South Vietnam in the Vietnam War. At the start of the decade, United States aid to South Vietnam consisted largely of supplies with approximately 900 military observers and trainers. After the assassination of both Ngo Dinh Diem and John F. Kennedy close to the end of 1963 and Gulf of Tonkin incident in 1964 and amid continuing political instability in the South, the Lyndon Johnson Administration made a policy commitment to safeguard the South Vietnamese regime directly. The American military forces and other anti-communist SEATO countries increased their support, sending large scale combat forces into South Vietnam; at its height in 1969, slightly more than 400,000 American troops were deployed. The People's Army of Vietnam and the allied Viet Cong fought back, keeping to countryside strongholds while the anti-communist allied forces tended to control the cities. The most notable conflict of this era was the 1968 Tet Offensive, a widespread campaign by the communist forces to attack across all of South Vietnam; while the offensive was largely repelled, it was a strategic success in seeding doubt as to the long-term viability of the South Vietnamese state. This phase of the war lasted until the election of Richard Nixon and the change of U.S. policy to Vietnamization, or ending the direct involvement and phased withdrawal of U.S. combat troops and giving the main combat role back to the South Vietnamese military.

The Sigma war games were a series of classified high level war games played in the Pentagon during the 1960s to strategize the conduct of the burgeoning Vietnam War. The games were designed to replicate then-current conditions in Indochina, with an aim toward predicting future events in the region. In almost all runs, the outcome was either a communist win, or a stalemate that led to protests in the US.

Sigma I-63 was one of the series of Sigma war games. These were a series of classified high level war games played in the Pentagon during the 1960s to strategize the conduct of the burgeoning Vietnam War. These simulations were designed to replicate then-current conditions in Indochina, with an aim toward predicting future foreign affairs events. They were staffed with high-ranking officials standing in to represent both domestic and foreign characters; stand-ins were chosen for their expertise concerning those they were called upon to represent. The games were supervised by a Control appointed to oversee both sides. The opposing Blue and Red Teams customary in war games were designated the friendly and enemy forces as was usual; however, several smaller teams were sometimes subsumed under Red and Blue Teams. Over the course of the games, the Red Team at times contained the Yellow Team for the People's Republic of China, the Brown Team for the Democratic Republic of Vietnam, the Black Team for the Viet Cong, and Green for the USSR.

The Sigma I-65 war game was one of a series of classified high level war games played in The Pentagon during the 1960s to strategize the conduct of the burgeoning Vietnam War. These simulations were designed to replicate then-current conditions in Indochina, with an aim toward predicting future foreign affairs events. They were staffed with high-ranking officials standing in to represent both domestic and foreign characters; stand-ins were chosen for their expertise concerning those they were called upon to represent. The games were supervised by a Control appointed to oversee both sides. The opposing Blue and Red Teams customary in war games were designated the friendly and enemy forces as was usual; however, several smaller teams were sometimes subsumed under Red and Blue Teams. Over the course of the games, the Red Team at times contained the Yellow Team for the People's Republic of China, the Brown Team for the Democratic Republic of Vietnam, the Black Team for the Viet Cong, and Green for the USSR.

The Sigma I-66 war game was one of a series of classified high level war games played in The Pentagon during the 1960s to strategize the conduct of the burgeoning Vietnam War. Sigma I-66 was based on the unrealistic scenario of a famine-stricken and militarily diminished North Vietnam agreeing to de-escalate its war efforts. It ended with a hypothetical force of 100,000 Viet Cong still in South Vietnam.

The Sigma II-66 war game was one of a series of classified high level war games played in the Pentagon during the 1960s to strategize the conduct of the burgeoning Vietnam War. The games were designed to replicate then-current conditions in Indochina, with an aim toward predicting future foreign affairs events. They were staffed with high ranking officials standing in to represent both domestic and foreign characters; stand-ins were chosen for their expertise concerning those they were called upon to represent. The games were supervised by a Control appointed to oversee both sides. The opposing Blue and Red Teams customary in war games were designated the friendly and enemy forces as was usual; however, several smaller teams were sometimes subsumed under Red and Blue Teams. Over the course of the games, the Red Team at times contained the Yellow Team for the People's Republic of China, the Brown Team for the Democratic Republic of Vietnam, the Black Team for the Viet Cong, and Green for the USSR.

The Sigma I-62 war game, played in February 1962, was the first of a series of classified high level war games played in the Pentagon during the 1960s to strategize the conduct of the burgeoning Vietnam War. These simulations were designed to replicate then-current conditions in Indochina, with an aim toward predicting future foreign affairs events. The conclusion drawn from Sigma I-62 was that American intervention in Vietnam would be unsuccessful.

The Sigma I-64 war game, one of the Sigma war games, was played from 6 to 9 April 1964. Its purpose was to test scenarios of escalation of warfare in Vietnam. After rigorous research into information needed to form a scenario, a simulation took place, with knowledgeable officials playing out the roles of actual government decision makers. Participants were drawn from the State Department, Department of Defense, the Central Intelligence Agency, and the Joint Chiefs of Staff. In Sigma I-64, the scenarios to be examined were the burgeoning Viet Cong insurgency in Vietnam, and the possible use of U.S. air power against it.

The Sigma II-65 war game was one of a series of classified high level war games played in the Pentagon during the 1960s to strategize the conduct of the burgeoning Vietnam War. It was held between 26 July and 5 August 1965. The games were designed to replicate then-current conditions in Indochina, with an aim toward predicting future foreign affairs events. They were staffed with high ranking officials standing in to represent both domestic and foreign characters; stand-ins were chosen for their expertise concerning those they were called upon to represent. The games were supervised by a Control appointed to oversee both sides. The opposing Blue and Red Teams customary in war games were designated the friendly and enemy forces as was usual; however, several smaller teams were sometimes subsumed under Red and Blue Teams. Over the course of the games, the Red Team at times contained the Yellow Team for the People's Republic of China, the Brown Team for the Democratic Republic of Vietnam, the Black Team for the Viet Cong, and Green for the USSR.

The Sigma I-67 and II-67 War Games were two of a series of classified high level war games played in the Pentagon during the 1960s to strategize the conduct of the burgeoning Vietnam War. The games were designed to replicate then-current conditions in Indochina, with an aim toward predicting future foreign affairs events. They were staffed with high-ranking officials standing in to represent both domestic and foreign characters; stand-ins were chosen for their expertise concerning those they were called upon to represent. The games were supervised by a Control appointed to oversee both sides. The opposing Blue and Red Teams customary in war games were designated the friendly and enemy forces as was usual; however, several smaller teams were sometimes subsumed under Red and Blue Teams. Over the course of the games, the Red Team at times contained the Yellow Team for the People's Republic of China, the Brown Team for the Democratic Republic of Vietnam, the Black Team for the Viet Cong, and Green for the USSR.

References

- Addington, Larry H. (2000) America's War in Vietnam: A Short Narrative History. Indiana University Press, ISBNs 0253213606, 978-0253213600.

- Allen, Thomas B. (1987) War Games: The Secret World of the Creators, Players, and Policy Makers Rehearsing World War III Today. McGraw-Hill. ISBNs 0070011958, 9780070011953.

- Bakich, Spencer D. (2014) Success and Failure in Limited War: Information and Strategy in the Korean, Vietnam, Persian Gulf, and Iraq Wars. University of Chicago Press. ISBNs 022610771X, 978-0226107714.

- Cornell, Tim and Thomas B. Allen. (2002) War and Games. Boydell Press. ISBNs 0851158706, 9780851158709.

- Elliott, Mai. (2010) RAND in Southeast Asia: A History of the Vietnam War Era. RAND Corporation. ISBNs 083304754X, 978-0833047540.

- Fawcett, Bill (2009) How to Lose a War: More Foolish Plans and Great Military Blunders. William Morrow Paperbacks. ISBNs 0061358444, 978-0061358449.

- Gibbons, William Conrad (1995) The U.S. Government and the Vietnam War. Princeton University Press. ISBNs 0691006350, 978-0691006352.

- Glain, Stephen (2011) State Vs. Defense: The Battle to Define America's Empire. Crown Publishers. ISBNs 0307408418, 9780307408419.

- Goldstein, Gordon M. (2008) Lessons in Disaster: McGeorge Bundy and the Path to War in Vietnam. Times Books. ISBNs 0805079718, 978-0805079715.

- McMaster, H. R. (1998) Dereliction of Duty: Johnson, McNamara, the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and the Lies That Led to Vietnam. Harper Perennial. ISBNs 0060929081, 978-0060929084.

- Milne, David (2009) America's Rasputin: Walt Rostow and the Vietnam War Hill and Wang. ISBNs 0374531625, 978-0374531621.

- Ross, Robert S. and Changbin Jiang (2001) Re-examining the Cold War: U.S.-China Diplomacy, 1954–1973. Harvard University Asia Center. ISBNs 0674005260, 9780674005266.

- Sorley, Lewis (1998) Honorable Warrior: General Harold K. Johnson and the Ethics of Command (Modern War Studies). University Press of Kansas. ISBNs 0700609520, 978-0700609529.

- Sigma II-64 final report (1964)