The Vietnam War was a conflict in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia from 1 November 1955 to the fall of Saigon on 30 April 1975. It was the second of the Indochina Wars and was a major conflict of the Cold War. While the war was officially fought between North Vietnam and South Vietnam, the north was supported by the Soviet Union, China, and other communist states, while the south was supported by the United States and other anti-communist allies, making the war a proxy war between the United States and the Soviet Union. It lasted almost 20 years, with direct U.S. military involvement ending in 1973. The conflict also spilled over into neighboring states, exacerbating the Laotian Civil War and the Cambodian Civil War, which ended with all three countries officially becoming communist states by 1976.

Robert Strange McNamara was an American businessman and government official who served as the eighth United States secretary of defense from 1961 to 1968 under presidents John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson. He remains the longest-serving secretary of defense, having remained in office over seven years. He played a major role in promoting the U.S.'s involvement in the Vietnam War. McNamara was responsible for the institution of systems analysis in public policy, which developed into the discipline known today as policy analysis.

The Taylor-Rostow Report was a report prepared in November 1961 on the situation in Vietnam in relation to Vietcong operations in South Vietnam. The report was written by General Maxwell Taylor, military representative to President John F. Kennedy, and Deputy National Security Advisor W.W. Rostow. Kennedy sent Taylor and Rostow to Vietnam in October 1961 to assess the deterioration of South Vietnam’s military position and the government's morale. The report called for improved training of Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN) troops, an infusion of American personnel into the South Vietnamese government and army, greater use of helicopters in counterinsurgency missions against North Vietnamese communists, consideration of bombing the North, and the commitment of 6,000-8,000 U.S. combat troops to Vietnam, albeit initially in a logistical role. The document was significant in that it seriously escalated the Kennedy Administration's commitment to Vietnam. It was also seen historically as having misdiagnosed the root of the Vietnam conflict as primarily a military rather than a political problem.

The Krulak–Mendenhall mission was a fact-finding expedition dispatched by the Kennedy administration to South Vietnam in early September 1963. The stated purpose of the expedition was to investigate the progress of the war by the South Vietnamese regime and its US military advisers against the Viet Cong insurgency. The mission was led by Victor Krulak and Joseph Mendenhall. Krulak was a major general in the United States Marine Corps, while Mendenhall was a senior Foreign Service Officer experienced in dealing with Vietnamese affairs.

The 1959 to 1963 phase of the Vietnam War started after the North Vietnamese had made a firm decision to commit to a military intervention in the guerrilla war in the South Vietnam, a buildup phase began, between the 1959 North Vietnamese decision and the Gulf of Tonkin Incident, which led to a major US escalation of its involvement. Vietnamese communists saw this as a second phase of their revolution, the US now substituting for the French.

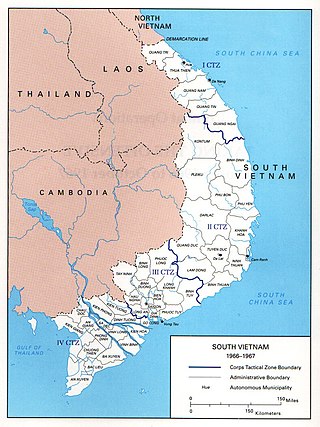

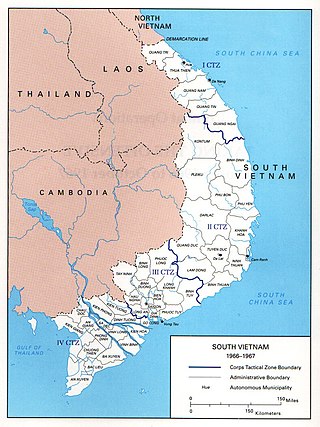

During the Cold War in the 1960s, the United States and South Vietnam began a period of gradual escalation and direct intervention referred to as the "Americanization" of joint warfare in South Vietnam during the Vietnam War. At the start of the decade, United States aid to South Vietnam consisted largely of supplies with approximately 900 military observers and trainers. After the assassination of both Ngo Dinh Diem and John F. Kennedy close to the end of 1963 and Gulf of Tonkin incident in 1964 and amid continuing political instability in the South, the Lyndon Johnson Administration made a policy commitment to safeguard the South Vietnamese regime directly. The American military forces and other anti-communist SEATO countries increased their support, sending large scale combat forces into South Vietnam; at its height in 1969, slightly more than 400,000 American troops were deployed. The People's Army of Vietnam and the allied Viet Cong fought back, keeping to countryside strongholds while the anti-communist allied forces tended to control the cities. The most notable conflict of this era was the 1968 Tet Offensive, a widespread campaign by the communist forces to attack across all of South Vietnam; while the offensive was largely repelled, it was a strategic success in seeding doubt as to the long-term viability of the South Vietnamese state. This phase of the war lasted until the election of Richard Nixon and the change of U.S. policy to Vietnamization, or ending the direct involvement and phased withdrawal of U.S. combat troops and giving the main combat role back to the South Vietnamese military.

In 1965, the United States rapidly increased its military forces in South Vietnam, prompted by the realization that the South Vietnamese government was losing the Vietnam War as the communist-dominated Viet Cong (VC) gained influence over much of the population in rural areas of the country. North Vietnam also rapidly increased its infiltration of men and supplies to combat South Vietnam and the U.S. The objective of the U.S. and South Vietnam was to prevent a communist take-over. North Vietnam and the VC sought to unite the two sections of the country.

National Security Action Memorandum Number 263 (NSAM-263) was a national security directive approved on 11 October 1963 by United States President John F. Kennedy. The NSAM approved recommendations by Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara and Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff General Maxwell Taylor. McNamara and Taylor's recommendations included an appraisal that "great progress" was being made in the Vietnam War against Viet Cong insurgents, that 1,000 military personnel could be withdrawn from South Vietnam by the end of 1963, and that a "major part of the U.S. military task can be completed by the end of 1965." The U.S. at this time had more than 16,000 military personnel in South Vietnam.

The Gulf of Tonkin Resolution or the Southeast Asia Resolution, Pub. L.Tooltip Public Law 88–408, 78 Stat. 384, enacted August 10, 1964, was a joint resolution that the United States Congress passed on August 7, 1964, in response to the Gulf of Tonkin incident.

Sigma I-63 was one of the series of Sigma war games. These were a series of classified high level war games played in the Pentagon during the 1960s to strategize the conduct of the burgeoning Vietnam War. These simulations were designed to replicate then-current conditions in Indochina, with an aim toward predicting future foreign affairs events. They were staffed with high-ranking officials standing in to represent both domestic and foreign characters; stand-ins were chosen for their expertise concerning those they were called upon to represent. The games were supervised by a Control appointed to oversee both sides. The opposing Blue and Red Teams customary in war games were designated the friendly and enemy forces as was usual; however, several smaller teams were sometimes subsumed under Red and Blue Teams. Over the course of the games, the Red Team at times contained the Yellow Team for the People's Republic of China, the Brown Team for the Democratic Republic of Vietnam, the Black Team for the Viet Cong, and Green for the USSR.

The Sigma I-65 war game was one of a series of classified high level war games played in The Pentagon during the 1960s to strategize the conduct of the burgeoning Vietnam War. These simulations were designed to replicate then-current conditions in Indochina, with an aim toward predicting future foreign affairs events. They were staffed with high-ranking officials standing in to represent both domestic and foreign characters; stand-ins were chosen for their expertise concerning those they were called upon to represent. The games were supervised by a Control appointed to oversee both sides. The opposing Blue and Red Teams customary in war games were designated the friendly and enemy forces as was usual; however, several smaller teams were sometimes subsumed under Red and Blue Teams. Over the course of the games, the Red Team at times contained the Yellow Team for the People's Republic of China, the Brown Team for the Democratic Republic of Vietnam, the Black Team for the Viet Cong, and Green for the USSR.

The Sigma I-66 war game was one of a series of classified high level war games played in The Pentagon during the 1960s to strategize the conduct of the burgeoning Vietnam War. Sigma I-66 was based on the unrealistic scenario of a famine-stricken and militarily diminished North Vietnam agreeing to de-escalate its war efforts. It ended with a hypothetical force of 100,000 Viet Cong still in South Vietnam.

The Sigma II-66 war game was one of a series of classified high level war games played in the Pentagon during the 1960s to strategize the conduct of the burgeoning Vietnam War. The games were designed to replicate then-current conditions in Indochina, with an aim toward predicting future foreign affairs events. They were staffed with high ranking officials standing in to represent both domestic and foreign characters; stand-ins were chosen for their expertise concerning those they were called upon to represent. The games were supervised by a Control appointed to oversee both sides. The opposing Blue and Red Teams customary in war games were designated the friendly and enemy forces as was usual; however, several smaller teams were sometimes subsumed under Red and Blue Teams. Over the course of the games, the Red Team at times contained the Yellow Team for the People's Republic of China, the Brown Team for the Democratic Republic of Vietnam, the Black Team for the Viet Cong, and Green for the USSR.

The Sigma I-62 war game, played in February 1962, was the first of a series of classified high level war games played in the Pentagon during the 1960s to strategize the conduct of the burgeoning Vietnam War. These simulations were designed to replicate then-current conditions in Indochina, with an aim toward predicting future foreign affairs events. The conclusion drawn from Sigma I-62 was that American intervention in Vietnam would be unsuccessful.

The Sigma I-64 war game, one of the Sigma war games, was played from 6 to 9 April 1964. Its purpose was to test scenarios of escalation of warfare in Vietnam. After rigorous research into information needed to form a scenario, a simulation took place, with knowledgeable officials playing out the roles of actual government decision makers. Participants were drawn from the State Department, Department of Defense, the Central Intelligence Agency, and the Joint Chiefs of Staff. In Sigma I-64, the scenarios to be examined were the burgeoning Viet Cong insurgency in Vietnam, and the possible use of U.S. air power against it.

The Sigma II-64 war game was one of a series of classified high level war games played in The Pentagon during the 1960s to strategize the conduct of the burgeoning Vietnam War. The games were designed to replicate then-current conditions in Indochina, with an aim toward predicting future foreign affairs events. They were staffed with high-ranking officials standing in to represent both domestic and foreign characters; stand-ins were chosen for their expertise concerning those they were called upon to represent. The games were supervised by a Control appointed to oversee both sides. The opposing Blue and Red Teams customary in war games were designated the friendly and enemy forces as was usual; however, several smaller teams were sometimes subsumed under Red and Blue Teams. Over the course of the games, the Red Team at times contained the Yellow Team for the People's Republic of China, the Brown Team for the Democratic Republic of Vietnam, the Black Team for the Viet Cong, and Green for the USSR.

The Sigma II-65 war game was one of a series of classified high level war games played in the Pentagon during the 1960s to strategize the conduct of the burgeoning Vietnam War. It was held between 26 July and 5 August 1965. The games were designed to replicate then-current conditions in Indochina, with an aim toward predicting future foreign affairs events. They were staffed with high ranking officials standing in to represent both domestic and foreign characters; stand-ins were chosen for their expertise concerning those they were called upon to represent. The games were supervised by a Control appointed to oversee both sides. The opposing Blue and Red Teams customary in war games were designated the friendly and enemy forces as was usual; however, several smaller teams were sometimes subsumed under Red and Blue Teams. Over the course of the games, the Red Team at times contained the Yellow Team for the People's Republic of China, the Brown Team for the Democratic Republic of Vietnam, the Black Team for the Viet Cong, and Green for the USSR.

The Sigma I-67 and II-67 War Games were two of a series of classified high level war games played in the Pentagon during the 1960s to strategize the conduct of the burgeoning Vietnam War. The games were designed to replicate then-current conditions in Indochina, with an aim toward predicting future foreign affairs events. They were staffed with high-ranking officials standing in to represent both domestic and foreign characters; stand-ins were chosen for their expertise concerning those they were called upon to represent. The games were supervised by a Control appointed to oversee both sides. The opposing Blue and Red Teams customary in war games were designated the friendly and enemy forces as was usual; however, several smaller teams were sometimes subsumed under Red and Blue Teams. Over the course of the games, the Red Team at times contained the Yellow Team for the People's Republic of China, the Brown Team for the Democratic Republic of Vietnam, the Black Team for the Viet Cong, and Green for the USSR.

National Security Action Memorandum 273 (NSAM-273) was approved by new United States President Lyndon Johnson on November 26, 1963, one day after former President John F. Kennedy's funeral. NSAM-273 resulted from the need to reassess U.S. policy toward the Vietnam War following the overthrow and assassination of President Ngo Dinh Diem. The first draft of NSAM-273, completed before Kennedy's death, was approved with minor changes by President Johnson.

The United States foreign policy during the 1963-1969 presidency of Lyndon B. Johnson was dominated by the Vietnam War and the Cold War, a period of sustained geopolitical tension between the United States and the Soviet Union. Johnson took over after the Assassination of John F. Kennedy, while promising to keep Kennedy's policies and his team.