Constantinople became the capital of the Roman Empire during the reign of Constantine the Great in 330. Following the collapse of the Western Roman Empire in the late 5th century, Constantinople remained the capital of the Eastern Roman Empire, the Latin Empire (1204–1261), and the Ottoman Empire (1453–1922). Following the Turkish War of Independence, the Turkish capital then moved to Ankara. Officially renamed Istanbul in 1930, the city is today the largest city and financial centre of Turkey and the largest city in Europe, straddling the Bosporus strait, lying in both Europe and Asia.

Justinian I, also known as Justinian the Great, was Eastern Roman emperor from 527 to 565.

The 6th century is the period from 501 through 600 in line with the Julian calendar.

The 550s decade ran from January 1, 550, to December 31, 559.

Year 552 (DLII) was a leap year starting on Monday of the Julian calendar. The denomination 552 for this year has been used since the early medieval period, when the Anno Domini calendar era became the prevalent method in Europe for naming years.

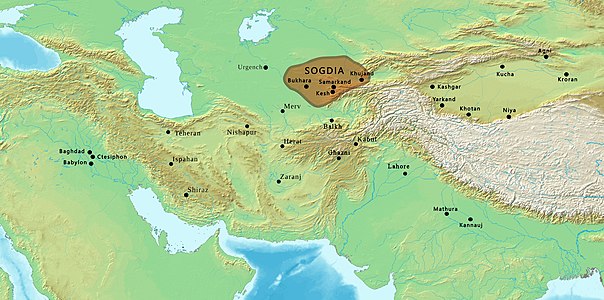

The Silk Road was a network of Eurasian trade routes active from the second century BCE until the mid-15th century. Spanning over 6,400 kilometers, it played a central role in facilitating economic, cultural, political, and religious interactions between the East and West. The name "Silk Road", first coined in the late 19th century, has fallen into disuse among some modern historians in favor of Silk Routes, on the grounds that it more accurately describes the intricate web of land and sea routes connecting Central, East, South, Southeast, and West Asia as well as East Africa and Southern Europe.

Maurice was Byzantine emperor from 582 to 602 and the last member of the Justinian dynasty. A successful general, Maurice was chosen as heir and son-in-law by his predecessor Tiberius II.

Justin II was Eastern Roman emperor from 565 until 578. He was the nephew of Justinian I and the husband of Sophia, the niece of the Empress Theodora, and a member of the Justinian dynasty.

The Kingdom of Khotan was an ancient Buddhist Saka kingdom located on the branch of the Silk Road that ran along the southern edge of the Taklamakan Desert in the Tarim Basin. The ancient capital was originally sited to the west of modern-day Hotan at Yotkan. From the Han dynasty until at least the Tang dynasty it was known in Chinese as Yutian. This largely Buddhist kingdom existed for over a thousand years until it was conquered by the Muslim Kara-Khanid Khanate in 1006, during the Islamization and Turkicization of Xinjiang.

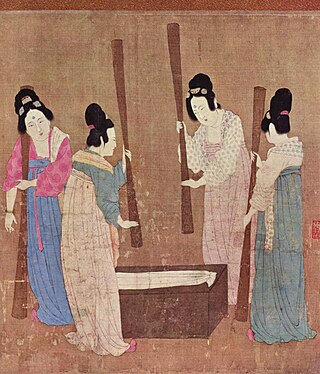

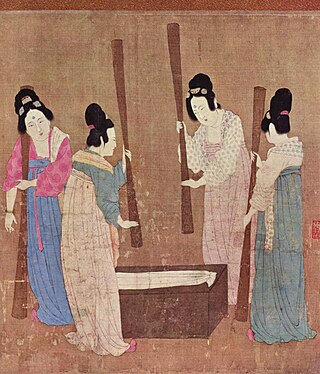

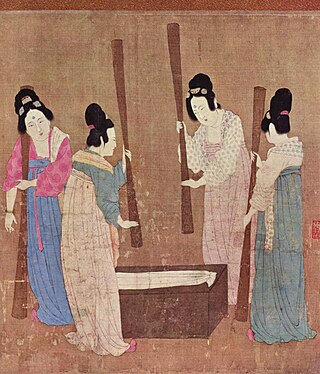

Sericulture, or silk farming, is the cultivation of silkworms to produce silk. Although there are several commercial species of silkworms, the caterpillar of the domestic silkmoth is the most widely used and intensively studied silkworm. Silk was believed to have first been produced in China as early as the Neolithic period. Sericulture has become an important cottage industry in countries such as Brazil, China, France, India, Italy, Japan, Korea, and Russia. Today, China and India are the two main producers, with more than 60% of the world's annual production.

Zemarchus was a Byzantine official, diplomat and traveller in the reign of Justin II.

Sino-Roman relations comprised the contacts and flows of trade goods, information, and occasional travelers between the Roman Empire and the Han dynasty, as well as between the later Eastern Roman Empire and various successive Chinese dynasties that followed. These empires inched progressively closer to each other in the course of the Roman expansion into ancient Western Asia and of the simultaneous Han military incursions into Central Asia. Mutual awareness remained low, and firm knowledge about each other was limited. Surviving records document only a few attempts at direct contact. Intermediate empires such as the Parthians and Kushans, seeking to maintain control over the lucrative silk trade, inhibited direct contact between these two Eurasian powers. In 97 AD the Chinese general Ban Chao tried to send his envoy Gan Ying to Rome, but Parthians dissuaded Gan from venturing beyond the Persian Gulf. Ancient Chinese historians recorded several alleged Roman emissaries to China. The first one on record, supposedly either from the Roman emperor Antoninus Pius or from his adopted son Marcus Aurelius, arrived in 166 AD. Others are recorded as arriving in 226 and 284 AD, followed by a long hiatus until the first recorded Byzantine embassy in 643 AD.

Istämi was the ruler of the western part of the Göktürks, which became the Western Turkic Khaganate and dominated the Sogdians. He was the yabgu (vassal) of his brother Bumin Qaghan in 552 AD. He was posthumously referred to as khagan in Turkic sources. His son was Tardu.

The production of silk originated in Neolithic China within the Yangshao culture. Though it would later reach other places in the world, the art of silk production remained confined to China until the Silk Road opened at 114 BC, though China maintained its virtual monopoly over silk production for another thousand years. The use of silk within China was not confined to clothing alone, and silk was used for a number of applications, such as writing. Within clothing, the color of silk worn also held social importance, and formed an important guide of social class during the Tang dynasty.

The Byzantine economy was among the most robust economies in the Mediterranean for many centuries. Constantinople was a prime hub in a trading network that at various times extended across nearly all of Eurasia and North Africa. Some scholars argue that, up until the arrival of the Arabs in the 7th century, the Eastern Roman Empire had the most powerful economy in the world. The Arab conquests, however, would represent a substantial reversal of fortunes contributing to a period of decline and stagnation. Constantine V's reforms marked the beginning of a revival that continued until 1204. From the 10th century until the end of the 12th, the Byzantine Empire projected an image of luxury, and the travelers were impressed by the wealth accumulated in the capital. All this changed with the arrival of the Fourth Crusade, which was an economic catastrophe. The Palaiologoi tried to revive the economy, but the late Byzantine state would not gain full control of either the foreign or domestic economic forces.

The Byzantine Empire was ruled by emperors of the dynasty of Heraclius between 610 and 711. The Heraclians presided over a period of cataclysmic events that were a watershed in the history of the Empire and the world. Heraclius, the founder of his dynasty, was of Armenian and Cappadocian (Greek) origin. At the beginning of the dynasty, the Empire's culture was still essentially Ancient Roman, dominating the Mediterranean and harbouring a prosperous Late Antique urban civilization. This world was shattered by successive invasions, which resulted in extensive territorial losses, financial collapse and plagues that depopulated the cities, while religious controversies and rebellions further weakened the Empire.

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire, was the continuation of the Roman Empire centered in Constantinople during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages. The eastern half of the Empire survived the conditions that caused the fall of the West in the 5th century AD, and continued to exist until the fall of Constantinople to the Ottoman Empire in 1453. During most of its existence, the empire remained the most powerful economic, cultural, and military force in the Mediterranean world. The term "Byzantine Empire" was only coined following the empire's demise: its citizens referred to the polity as the "Roman Empire" and to themselves as "Romans". Due to the imperial seat's move from Rome to Byzantium, the adoption of state Christianity, and the predominance of Greek instead of Latin, modern historians continue to make a distinction between the earlier "Roman Empire" and the later "Byzantine Empire".

This history of the Byzantine Empire covers the history of the Eastern Roman Empire from late antiquity until the Fall of Constantinople in 1453 AD. Several events from the 4th to 6th centuries mark the transitional period during which the Roman Empire's east and west divided. In 285, the emperor Diocletian partitioned the Roman Empire's administration into eastern and western halves. Between 324 and 330, Constantine I transferred the main capital from Rome to Byzantium, later known as Constantinople and Nova Roma. Under Theodosius I, Christianity became the Empire's official state religion and others such as Roman polytheism were proscribed. Finally, under the reign of Heraclius, the Empire's military and administration were restructured and adopted Greek for official use instead of Latin. Although the Roman state continued, some historians choose to distinguish the Byzantine Empire from the earlier Roman Empire due to the imperial seat moving from Rome to Byzantium, the Empire’s integration of Christianity, and the predominance of Greek instead of Latin.

Byzantine silk is silk woven in the Byzantine Empire (Byzantium) from about the fourth century until the Fall of Constantinople in 1453.

The term Byzantine Dark Ages is a historiographical term for the period in the history of the Eastern Roman (Byzantine) Empire, during the 7th and 8th centuries, which marks the transition between the late antique early Byzantine period and the "medieval" middle Byzantine era. The "Dark Ages" are characterized by widespread upheavals and transformation of the Byzantine state and society, resulting in a paucity of historical sources.