Related Research Articles

Friedrich August von Hayek, often referred to by his initials F. A. Hayek, was an Austrian-British economist and political philosopher who made contributions to economics, political philosophy, psychology, intellectual history, and other fields. Hayek shared the 1974 Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences with Gunnar Myrdal for work on money and economic fluctuations, and the interdependence of economic, social and institutional phenomena. His account of how prices communicate information is widely regarded as an important contribution to economics that led to him receiving the prize.

Keynesian economics are the various macroeconomic theories and models of how aggregate demand strongly influences economic output and inflation. In the Keynesian view, aggregate demand does not necessarily equal the productive capacity of the economy. Instead, it is influenced by a host of factors – sometimes behaving erratically – affecting production, employment, and inflation.

In economics, general equilibrium theory attempts to explain the behavior of supply, demand, and prices in a whole economy with several or many interacting markets, by seeking to prove that the interaction of demand and supply will result in an overall general equilibrium. General equilibrium theory contrasts with the theory of partial equilibrium, which analyzes a specific part of an economy while its other factors are held constant. In general equilibrium, constant influences are considered to be noneconomic, or in other words, considered to be beyond the scope of economic analysis. The noneconomic influences may change given changes in the economic factors however, and therefore the prediction accuracy of an equilibrium model may depend on the independence of the economic factors from noneconomic ones.

Post-Keynesian economics is a school of economic thought with its origins in The General Theory of John Maynard Keynes, with subsequent development influenced to a large degree by Michał Kalecki, Joan Robinson, Nicholas Kaldor, Sidney Weintraub, Paul Davidson, Piero Sraffa and Jan Kregel. Historian Robert Skidelsky argues that the post-Keynesian school has remained closest to the spirit of Keynes' original work. It is a heterodox approach to economics.

Piero Sraffa, FBA was an influential Italian economist who served as lecturer of economics at the University of Cambridge. His book Production of Commodities by Means of Commodities is taken as founding the neo-Ricardian school of economics.

Nicholas Kaldor, Baron Kaldor, born Káldor Miklós, was a Cambridge economist in the post-war period. He developed the "compensation" criteria called Kaldor–Hicks efficiency for welfare comparisons (1939), derived the cobweb model, and argued for certain regularities observable in economic growth, which are called Kaldor's growth laws. Kaldor worked alongside Gunnar Myrdal to develop the key concept Circular Cumulative Causation, a multicausal approach where the core variables and their linkages are delineated. Both Myrdal and Kaldor examine circular relationships, where the interdependencies between factors are relatively strong, and where variables interlink in the determination of major processes. Gunnar Myrdal got the concept from Knut Wicksell and developed it alongside Nicholas Kaldor when they worked together at the United Nations Economic Commission for Europe. Myrdal concentrated on the social provisioning aspect of development, while Kaldor concentrated on demand-supply relationships to the manufacturing sector. Kaldor also coined the term "convenience yield" related to commodity markets and the so-called theory of storage, which was initially developed by Holbrook Working.

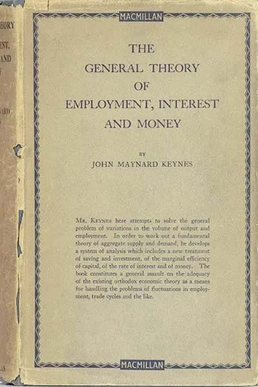

The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money is a book by English economist John Maynard Keynes published in February 1936. It caused a profound shift in economic thought, giving macroeconomics a central place in economic theory and contributing much of its terminology – the "Keynesian Revolution". It had equally powerful consequences in economic policy, being interpreted as providing theoretical support for government spending in general, and for budgetary deficits, monetary intervention and counter-cyclical policies in particular. It is pervaded with an air of mistrust for the rationality of free-market decision making.

Maurice Herbert Dobb was an English economist at Cambridge University and a Fellow of Trinity College, Cambridge. He is remembered as one of the pre-eminent Marxist economists of the 20th century.

Neutrality of money is the idea that a change in the stock of money affects only nominal variables in the economy such as prices, wages, and exchange rates, with no effect on real variables, like employment, real GDP, and real consumption. Neutrality of money is an important idea in classical economics and is related to the classical dichotomy. It implies that the central bank does not affect the real economy by creating money. Instead, any increase in the supply of money would be offset by a proportional rise in prices and wages. This assumption underlies some mainstream macroeconomic models. Others like monetarism view money as being neutral only in the long run.

Michio Morishima was a Japanese heterodox economist and public intellectual who was the Sir John Hicks Professor of Economics at the London School of Economics from 1970–88. He was also professor at Osaka University and member of the British Academy. In 1976 he won the Order of Culture.

Fritz Machlup was an Austrian-American economist who was president of the International Economic Association from 1971 to 1974. He was one of the first economists to examine knowledge as an economic resource, and is credited with popularizing the concept of the information society.

The Austrian business cycle theory (ABCT) is an economic theory developed by the Austrian School of economics about how business cycles occur. The theory views business cycles as the consequence of excessive growth in bank credit due to artificially low interest rates set by a central bank or fractional reserve banks. The Austrian business cycle theory originated in the work of Austrian School economists Ludwig von Mises and Friedrich Hayek. Hayek won the Nobel Prize in Economics in 1974 in part for his work on this theory.

The neoclassical synthesis (NCS), neoclassical–Keynesian synthesis, or just neo-Keynesianism was a neoclassical economics academic movement and paradigm in economics that worked towards reconciling the macroeconomic thought of John Maynard Keynes in his book The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money (1936). It was formulated most notably by John Hicks (1937), Franco Modigliani (1944), and Paul Samuelson (1948), who dominated economics in the post-war period and formed the mainstream of macroeconomic thought in the 1950s, 60s, and 70s.

In economics, the loanable funds doctrine is a theory of the market interest rate. According to this approach, the interest rate is determined by the demand for and supply of loanable funds. The term loanable funds includes all forms of credit, such as loans, bonds, or savings deposits.

Luigi L. Pasinetti was an Italian economist of the post-Keynesian school. Pasinetti was considered the heir of the "Cambridge Keynesians" and a student of Piero Sraffa and Richard Kahn. Along with them, as well as Joan Robinson, he was one of the prominent members on the "Cambridge, UK" side of the Cambridge capital controversy. His contributions to economics include developing the analytical foundations of neo-Ricardian economics, including the theory of value and distribution, as well as work in the line of Kaldorian theory of growth and income distribution. He also developed the theory of structural change and economic growth, structural economic dynamics and uneven sectoral development.

Macroeconomic theory has its origins in the study of business cycles and monetary theory. In general, early theorists believed monetary factors could not affect real factors such as real output. John Maynard Keynes attacked some of these "classical" theories and produced a general theory that described the whole economy in terms of aggregates rather than individual, microeconomic parts. Attempting to explain unemployment and recessions, he noticed the tendency for people and businesses to hoard cash and avoid investment during a recession. He argued that this invalidated the assumptions of classical economists who thought that markets always clear, leaving no surplus of goods and no willing labor left idle.

A Treatise on Money is a two-volume book by English economist John Maynard Keynes published in 1930.

The Cambridge capital controversy, sometimes called "the capital controversy" or "the two Cambridges debate", was a dispute between proponents of two differing theoretical and mathematical positions in economics that started in the 1950s and lasted well into the 1960s. The debate concerned the nature and role of capital goods and a critique of the neoclassical vision of aggregate production and distribution. The name arises from the location of the principals involved in the controversy: the debate was largely between economists such as Joan Robinson and Piero Sraffa at the University of Cambridge in England and economists such as Paul Samuelson and Robert Solow at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, in Cambridge, Massachusetts, United States.

John Hicks's 1937 paper Mr. Keynes and the "Classics"; a suggested interpretation is the most influential study of the views presented by J. M. Keynes in his General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money of February 1936. It gives "a potted version of the central argument of the General Theory" as an equilibrium specified by two equations which dominated Keynesian teaching until Axel Leijonhufvud published a critique in 1968. Leijonhufvud's view that Hicks misrepresented Keynes's theory by reducing it to a static system was in turn rejected by many economists who considered much of the General Theory to be as static as Hicks portrayed it.

Mabel Timlin was a Canadian economist who in 1950, became the first tenured woman economics professor at a Canadian university. Timlin was a pioneer in the field of economics and is best known for her work and interpretation of Keynesian theory, as well as Canadian immigration policy and post WWII monetary stabilization policy. In addition to her successful research career, Timlin was the first woman to serve as vice president and president of the Canadian Political Science Association. She was also one of the first women and one of the very few Canadian economists to serve on the Executive Committee of the American Economic Association.

References

- ↑ F. A. Hayek, "Reflection on the pure theory of money of Mr. J. M. Keynes," Economica, 11, S. 270–95 (1931).

- 1 2 F. A. Hayek, Prices and Production, (London: Routledge, 1931).

- ↑ Keynes, J. M. (1931). "The Pure Theory of Money. A Reply to Dr. Hayek". Economica (34): 387–397. doi:10.2307/2549192. ISSN 0013-0427.

- 1 2 Sraffa, Piero (1932). "Dr. Hayek on Money and Capital". The Economic Journal. 42 (165): 42–53. doi:10.2307/2223735. ISSN 0013-0133.

- ↑ von Hayek, F. A. (1932). "Money and Capital: A Reply". The Economic Journal. 42 (166): 237–249. doi:10.2307/2223821. ISSN 0013-0133.

- ↑ Sraffa, Piero (1932). "[Money and Capital]: A Rejoinder". The Economic Journal. 42 (166): 249–251. doi:10.2307/2223822. ISSN 0013-0133.