A gunnies, gunnis, or gunniss is the space left in a mine after the extraction by stoping of a vertical or near vertical ore-bearing lode. The term is also used when this space breaks the surface of the ground, but it can then be known as a coffin or goffen. It can also be used to describe the deep trenches that were dug by early miners in following the ore-bearing lode downwards from the surface – in this case they are often called open-works; their existence can provide the earliest evidence of mining in an area. William Pryce, writing in 1778, also used the term as a measure of width, a single gunnies being equal to three feet.

Underground hard-rock mining refers to various underground mining techniques used to excavate "hard" minerals, usually those containing metals, such as ore containing gold, silver, iron, copper, zinc, nickel, tin, and lead. It also involves the same techniques used to excavate ores of gems, such as diamonds and rubies. Soft-rock mining refers to the excavation of softer minerals, such as salt, coal, and oil sands.

Open-pit mining, also known as open-cast or open-cut mining and in larger contexts mega-mining, is a surface mining technique that extracts rock or minerals from the earth.

A borehole is a narrow shaft bored in the ground, either vertically or horizontally. A borehole may be constructed for many different purposes, including the extraction of water, other liquids, or gases. It may also be part of a geotechnical investigation, environmental site assessment, mineral exploration, temperature measurement, as a pilot hole for installing piers or underground utilities, for geothermal installations, or for underground storage of unwanted substances, e.g. in carbon capture and storage.

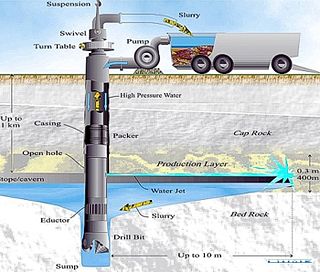

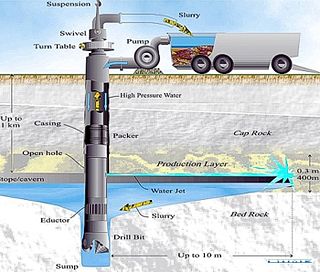

Borehole Mining (BHM) is a remote operated method of extraction (mining) of mineral resources through boreholes based on in-situ conversion of ores into a mobile form (slurry) by means of high pressure water jetting (hydraulicking). This process is carried-out from a land surface, open pit floor, underground mine or floating vessel through pre-drilled boreholes.

Surface mining, including strip mining, open-pit mining and mountaintop removal mining, is a broad category of mining in which soil and rock overlying the mineral deposit are removed, in contrast to underground mining, in which the overlying rock is left in place, and the mineral is removed through shafts or tunnels.

Shaft mining or shaft sinking is the action of excavating a mine shaft from the top down, where there is initially no access to the bottom. Shallow shafts, typically sunk for civil engineering projects, differ greatly in execution method from deep shafts, typically sunk for mining projects.

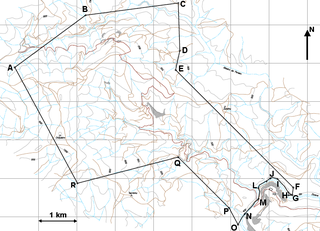

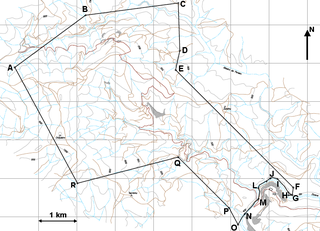

Minas da Panasqueira or Mina da Panasqueira is the generic name for a set of mining operations between Cabeço do Pião and the village of Panasqueira, which has operated in a technically integrated and continuous manner practically since the discovery of ore there. Subsequently, it was agglomerated into a single administrative entity called Couto Mineiro da Panasqueira which had its last demarcation on 9 March 1971 and later on in the present C-18 Mining Concession. The mining facilities are currently centralized in the area of Barroca Grande – Aldeia de São Francisco de Assis (Covilhã) through which the current underground operation, ore extraction and processing facilities are accessed.

Mine exploration is a hobby in which people visit abandoned mines, quarries, and sometimes operational mines. Enthusiasts usually engage in such activities for the purpose of exploration and documentation, sometimes through the use of surveying and photography. In this respect, mine exploration might be considered a type of amateur industrial archaeology. In many ways, however, it is closer to caving, with many participants actively interested in exploring both mines and caves. Mine exploration typically requires equipment such as helmets, head lamps, Wellington boots, and climbing gear.

Kidd Mine or Kidd Creek Mine is an underground base metal (copper-zinc-silver) mine 24 km (15 mi) north of Timmins, Ontario, Canada. It is owned and operated by Swiss multinational Glencore Inc. The mine was discovered in 1963 by Texas Gulf Sulfur Company. In 1981, it was sold to Canada Development Corporation, then sold in 1986 to Falconbridge Ltd., which in 2006 was acquired by Xstrata, which in turn merged with Glencore in 2013. Ore from the Kidd Mine is processed into concentrate at the Kidd Metallurgical Site, located 27 km (17 mi) southeast of the mine, which until 2010 also smelted the ore and refined the metal produced. Following the closure of the majority of the Met Site, concentrate is now shipped to Quebec for processing. Kidd Mine is the world's deepest copper-zinc mine.

Room and pillar or pillar and stall is a variant of breast stoping. It is a mining system in which the mined material is extracted across a horizontal plane, creating horizontal arrays of rooms and pillars. To do this, "rooms" of ore are dug out while "pillars" of untouched material are left to support the roof – overburden. Calculating the size, shape, and position of pillars is a complicated procedure, and an area of active research. The technique is usually used for relatively flat-lying deposits, such as those that follow a particular stratum. Room and pillar mining can be advantageous because it reduces the risk of surface subsidence compared to other underground mining techniques. It is also advantageous because it can be mechanized, and is relatively simple. However, because significant portions of ore may have to be left behind, recovery and profits can be low. Room and pillar mining was one of the earliest methods used, although with significantly more manpower.

In-situ leaching (ISL), also called in-situ recovery (ISR) or solution mining, is a mining process used to recover minerals such as copper and uranium through boreholes drilled into a deposit, in situ. In-situ leach works by artificially dissolving minerals occurring naturally in the solid state.

The following outline is provided as an overview of and topical guide to mining:

Boring is drilling a hole, tunnel, or well in the Earth. It is used for various applications in geology, agriculture, hydrology, civil engineering, and mineral exploration. Today, most Earth drilling serves one of the following purposes:

Mining in the Upper Harz region of central Germany was a major industry for several centuries, especially for the production of silver, lead, copper, and, latterly, zinc as well. Great wealth was accumulated from the mining of silver from the 16th to the 19th centuries, as well as from important technical inventions. The centre of the mining industry was the group of seven Upper Harz mining towns of Clausthal, Zellerfeld, Sankt Andreasberg, Wildemann, Grund, Lautenthal und Altenau.

The Kemi Mine is owned by Outokumpu Chrome Oy, a subsidiary of Outokumpu Oyj. It is located in Elijärvi, in the municipality of Keminmaa, to the north of Kemi. The Kemi Mine is the largest underground mine in Finland, with an annual production capacity of 2.7 million tonnes of ore. It is also part of the integrated ferrochrome and stainless steel manufacturing chain owned by Outokumpu in the Kemi-Tornio region. The Kemi Mine has approximately 400 employees every day, both employees of Outokumpu and contractors.

Zinc mining is the process by which mineral forms of the metal zinc are extracted from the earth through mining. A zinc mine is a mine that produces zinc minerals in ore as its primary product. Common co-products in zinc ores include minerals of lead and silver. Other mines may produce zinc minerals as a by-product of the production of ores containing more valuable minerals or metals, such as gold, silver or copper. Mined ore is processed, usually on site, to produce one or more metal-rich concentrates, then transported to a zinc smelter for production of zinc metal.

The Sumdum mine is one of the largest lead and zinc mines in United States. The mine is located in north-western United States in Alaska. The mine has reserves amounting to 24 million tonnes of ore grading 0.37% zinc and 79.1 million oz of silver.

The Pogo mine is a gold mine in the state of Alaska. By 31 December 2017 Pogo had produced 3.6 million ounces of gold at a grade of 13.6 g/t. Annual production for 2020 was 205,878 ounces. At 31 December 2019 the mine had Proven and Probable Reserves of 1.5 million ounces of gold at a grade of 7.5 g/t (JORC). It is located 30 miles (48 km) northeast of Delta Junction and 90 miles (145 km) east of Fairbanks. Northern Star Resources Ltd announced in May 2020 that it had entered into an agreement with the Japan-based Sumitomo Metal Mining Co and Sumitomo Corp to acquire the Pogo Gold mine.

The Rajpura Dariba Mine VRM disaster took place in Dariba, Udaipur, India on 28 August 1994 at a mine operated by Hindustan Zinc Ltd.