An astronomical clock, horologium, or orloj is a clock with special mechanisms and dials to display astronomical information, such as the relative positions of the Sun, Moon, zodiacal constellations, and sometimes major planets.

Strasbourg Cathedral or the Cathedral of Our Lady of Strasbourg, also known as Strasbourg Minster, is a Catholic cathedral in Strasbourg, Alsace, France. Although considerable parts of it are still in Romanesque architecture, it is widely considered to be among the finest examples of Rayonnant Gothic architecture. Architect Erwin von Steinbach is credited for major contributions from 1277 to his death in 1318, and beyond through his son Johannes von Steinbach, and his grandson Gerlach von Steinbach, who succeeded him as chief architects. The Steinbachs’ plans for the completion of the cathedral were not followed through by the chief architects who took over after them, and instead of the originally envisioned two spires, a single, octagonal tower with an elongated, octagonal crowning was built on the northern side of the west facade by master Ulrich Ensingen and his successor, Johannes Hültz. The construction of the cathedral, which had started in the year 1015 and had been relaunched in 1190, was finished in 1439.

Clocks and watches with a 24-hour analog dial have an hour hand that makes one complete revolution, 360°, in a day. The more familiar 12-hour analog dial has an hour hand that makes two complete revolutions in a day.

Conrad Dasypodius was a Swiss astronomer, mathematician, and writer. He was a professor of mathematics in Strasbourg, Alsace. He was born in Frauenfeld, Thurgau, Switzerland. His first name was also rendered as Konrad or Conradus or Cunradus, and his last name has been alternatively stated as Rauchfuss, Rauchfuß, and Hasenfratz. He was the son of Petrus Dasypodius, a humanist and lexicographer.

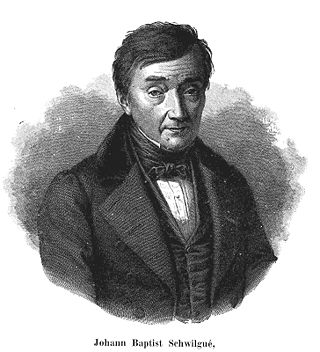

Jean-Baptiste Schwilgué (1776–1856) was the author of the third astronomical clock of Strasbourg Cathedral, built between 1838 and 1843 . In 1844 Schwilgué, together with his son Charles, patented a key-driven calculating machine, which seems to be the third key-driven machine in the world, after that of Luigi Torchi (1834) and James White (1822).

Isaac (1544–1620) and Josias (1552–1575) Habrecht were two clockmaker brothers from Schaffhausen, Switzerland.

Jens Olsen was a clockmaker, locksmith and astromechanic who built the famous world clock located in the city hall of Copenhagen, the Rådhus. He was born in Ribe, Denmark. Ever since he was a small child, Olsen was interested in clocks and other mechanical devices. After hearing of the broken clock in Carsten Hauch's A Polish Family, he dreamed of fixing that clock. Later, he envisioned a clock that would show every conceivable type of time, from sidereal time to the rotation of the planets.

St Mark's Clock is housed in the Clock Tower on the Piazza San Marco in Venice, Italy, adjoining the Procuratie Vecchie. The first clock housed in the tower was built and installed by Gian Paolo and Gian Carlo Rainieri, father and son, between 1496 and 1499, and was one of a number of large public astronomical clocks erected throughout Europe during the 14th and 15th centuries. The clock has had an eventful horological history, and been the subject of many restorations, some controversial.

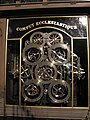

Klinghammer's computus is a mechanism determining the elements of the computus, in particular the date of Easter in the Gregorian calendar. This mechanism was built in the 1970s by Frédéric Klinghammer (1908–2006) and is nearly a reduced model of the computus found on the Strasbourg cathedral astronomical clock.

The Besançon astronomical clock is housed in Besançon Cathedral. Auguste-Lucien Vérité of Beauvais designed and built Besançon's present astronomical clock, between 1858 and 1863. It replaced an earlier clock that Bernardin had constructed in the 1850s that proved unsatisfactory. Besançon's clock differs from those in Strasbourg, Lyon, and Beauvais. The clock is meant to express the theological concept that each second of the day the Resurrection of Christ transforms the existence of man and of the world.

Astronomical rings, also known as Gemma's rings, are an early astronomical instrument. The instrument consists of three rings, representing the celestial equator, declination, and the meridian.

Lund astronomical clock, occasionally and at least since the 16th century referred to as Horologium mirabile Lundense, is a 15th-century astronomical clock in Lund Cathedral. Mentioned in written sources for the first time in 1442, it was probably made and installed sometime around 1423–1425, possibly by Nikolaus Lilienfeld. It is part of a group of related medieval astronomical clocks found in the area around the south Baltic Sea. In 1837 the clock was dismantled. Between 1909 and 1923, it was restored by the Danish clockmaker Julius Bertram-Larsen and the Swedish architect responsible for the upkeep of the cathedral, Theodor Wåhlin. From the old clock, the face of the clock as well as the mechanism, which was largely replaced during the 18th century, was salvaged and re-used. The casing, most parts of the calendar which occupies the lower part, and the middle section were made anew.

The Lyon astronomical clock is a seventeenth-century astronomical clock in Lyon Cathedral.

The Ploërmel Astronomical Clock is a 19th-century astronomical clock in Ploërmel in Brittany, in north-west France.

The Museé alsacien is one of the three museums of Haguenau, France. Like its older and much larger counterpart in Strasbourg, it is dedicated to local, mostly rural customs, furniture, and folk art.

The astronomical clock of Messina is an astronomical clock constructed by the Ungerer Company of Strasbourg in 1933. It is built into the campanile of Messina Cathedral.

A computus clock is a clock equipped with a mechanism that automatically calculates and displays, or helps determine, the date of Easter. A computus watch carries out the same function.

The Münster astronomical clock is an astronomical clock in Münster Cathedral in Münster, Germany.

The Bourges astronomical clock is an astronomical clock in Bourges Cathedral in Bourges, France.