Related Research Articles

The Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty, also known as the ABM Treaty or ABMT, was an arms control treaty between the United States and the Soviet Union on the limitation of the anti-ballistic missile (ABM) systems used in defending areas against ballistic missile-delivered nuclear weapons. It was intended to reduce pressures to build more nuclear weapons to maintain deterrence. Under the terms of the treaty, each party was limited to two ABM complexes, each of which was to be limited to 100 anti-ballistic missiles.

Nuclear disarmament is the act of reducing or eliminating nuclear weapons. Its end state can also be a nuclear-weapons-free world, in which nuclear weapons are completely eliminated. The term denuclearization is also used to describe the process leading to complete nuclear disarmament.

Nuclear warfare, also known as atomic warfare, is a military conflict or prepared political strategy that deploys nuclear weaponry. Nuclear weapons are weapons of mass destruction; in contrast to conventional warfare, nuclear warfare can produce destruction in a much shorter time and can have a long-lasting radiological result. A major nuclear exchange would likely have long-term effects, primarily from the fallout released, and could also lead to secondary effects, such as "nuclear winter", nuclear famine, and societal collapse. A global thermonuclear war with Cold War-era stockpiles, or even with the current smaller stockpiles, may lead to various scenarios including human extinction.

In nuclear strategy, a first strike or preemptive strike is a preemptive surprise attack employing overwhelming force. First strike capability is a country's ability to defeat another nuclear power by destroying its arsenal to the point where the attacking country can survive the weakened retaliation while the opposing side is left unable to continue war. The preferred methodology is to attack the opponent's strategic nuclear weapon facilities, command and control sites, and storage depots first. The strategy is called counterforce.

Mutual assured destruction (MAD) is a doctrine of military strategy and national security policy which posits that a full-scale use of nuclear weapons by an attacker on a nuclear-armed defender with second-strike capabilities would result in the complete annihilation of both the attacker and the defender. It is based on the theory of rational deterrence, which holds that the threat of using strong weapons against the enemy prevents the enemy's use of those same weapons. The strategy is a form of Nash equilibrium in which, once armed, neither side has any incentive to initiate a conflict or to disarm.

In nuclear ethics and deterrence theory, no first use (NFU) refers to a type of pledge or policy wherein a nuclear power formally refrains from the use of nuclear weapons or other weapons of mass destruction (WMD) in warfare, except for as a second strike in retaliation to an attack by an enemy power using WMD. Such a pledge would allow for a unique state of affairs in which a given nuclear power can be engaged in a conflict of conventional weaponry while it formally forswears any of the strategic advantages of nuclear weapons, provided the enemy power does not possess or utilize any such weapons of their own. The concept is primarily invoked in reference to nuclear mutually assured destruction but has also been applied to chemical and biological warfare, as is the case of the official WMD policy of India.

World War III, also known as the Third World War, is a hypothetical future global conflict subsequent to World War I (1914–1918) and World War II (1939–1945). It is widely assumed that such a war would involve all of the great powers, like its predecessors, as well as the use of nuclear weapons or other weapons of mass destruction, surpassing all prior conflicts in geographic scope, devastation and loss of life.

The nuclear arms race was an arms race competition for supremacy in nuclear warfare between the United States, the Soviet Union, and their respective allies during the Cold War. During this same period, in addition to the American and Soviet nuclear stockpiles, other countries developed nuclear weapons, though no other country engaged in warhead production on nearly the same scale as the two superpowers.

The Single Integrated Operational Plan (SIOP) was the United States' general plan for nuclear war from 1961 to 2003. The SIOP gave the President of the United States a range of targeting options, and described launch procedures and target sets against which nuclear weapons would be launched. The plan integrated the capabilities of the nuclear triad of strategic bombers, land-based intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBM), and sea-based submarine-launched ballistic missiles (SLBM). The SIOP was a highly classified document, and was one of the most secret and sensitive issues in U.S. national security policy.

Flexible response was a defense strategy implemented by John F. Kennedy in 1961 to address the Kennedy administration's skepticism of Dwight Eisenhower's New Look and its policy of massive retaliation. Flexible response calls for mutual deterrence at strategic, tactical, and conventional levels, giving the United States the capability to respond to aggression across the spectrum of war, not limited only to nuclear arms.

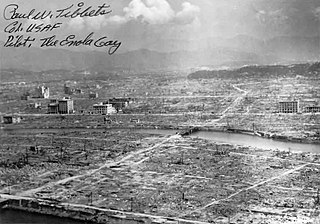

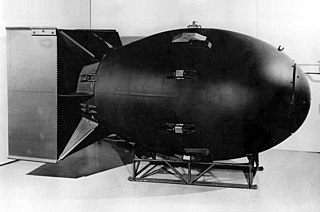

The nuclear weapons debate refers to the controversies surrounding the threat, use and stockpiling of nuclear weapons. Even before the first nuclear weapons had been developed, scientists involved with the Manhattan Project were divided over the use of the weapon. The only time nuclear weapons have been used in warfare was during the final stages of World War II when USAAF B-29 Superfortress bombers dropped atomic bombs on the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in early August 1945. The role of the bombings in Japan's surrender and the U.S.'s ethical justification for them have been the subject of scholarly and popular debate for decades.

Deterrence & Survival in the Nuclear Age, commonly referred to as the Gaither report, is a report submitted in November 1957 to the United States National Security Council and the U.S. president concerning strategy to prepare against the perceived threat of a nuclear attack from the Soviet Union.

In nuclear strategy, a retaliatory strike or second-strike capability is a country's assured ability to respond to a nuclear attack with powerful nuclear retaliation against the attacker. To have such an ability is considered vital in nuclear deterrence, as otherwise the other side might attempt to try to win a nuclear war in one massive first strike against its opponent's own nuclear forces.

Launch on warning (LOW), or fire on warning, is a strategy of nuclear weapon retaliation where a retaliatory strike is launched upon warning of enemy nuclear attack and while its missiles are still in the air, before detonation occurs. It gained recognition during the Cold War between the Soviet Union and the United States. With the invention of intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs), launch on warning became an integral part of mutually-assured destruction (MAD) theory. US land-based missiles can reportedly be launched within 5 minutes of a presidential decision to do so and submarine-based missiles within 15 minutes.

A nuclear triad is a three-pronged military force structure of land-based intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs), submarine-launched ballistic missiles (SLBMs), and strategic bombers with nuclear bombs and missiles. Countries build nuclear triads to eliminate an enemy's ability to destroy a nation's nuclear forces in a first-strike attack, which preserves their own ability to launch a second strike and therefore increases their nuclear deterrence.

The President's Science Advisory Committee (PSAC) was created on November 21, 1957, by President of the United States Dwight D. Eisenhower, as a direct response to the Soviet launching of the Sputnik 1 and Sputnik 2 satellites. PSAC was an upgrade and move to the White House of the Science Advisory Committee (SAC) established in 1951 by President Harry S. Truman, as part of the Office of Defense Mobilization (ODM). Its purpose was to advise the president on scientific matters in general, and those related to defense issues in particular. Eisenhower appointed James R. Killian as PSAC's first director.

A strategic nuclear weapon (SNW) refers to a nuclear weapon that is designed to be used on targets often in settled territory far from the battlefield as part of a strategic plan, such as military bases, military command centers, arms industries, transportation, economic, and energy infrastructure, and countervalue targets such areas such as cities and towns. It is in contrast to a tactical nuclear weapon, which is designed for use in battle as part of an attack with and often near friendly conventional forces, possibly on contested friendly territory. As of 2024, strategic nuclear weapons have been used twice in the 1945 United States bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

Dead Hand, also known as Perimeter, is a Cold War–era automatic or semi-automatic nuclear weapons control system that was constructed by the Soviet Union. The system remains in use in the post-Soviet Russian Federation. An example of fail-deadly and mutual assured destruction deterrence, it can initiate the launch of the Russian intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs) by sending a pre-entered highest-authority order from the General Staff of the Armed Forces, Strategic Missile Force Management to command posts and individual silos if a nuclear strike is detected by seismic, light, radioactivity, and pressure sensors even with the commanding elements fully destroyed. By most accounts, it is normally switched off and is supposed to be activated during times of crisis; however, as of 2009, it was said to remain fully functional and able to serve its purpose when needed. Accounts differ on whether the system, once activated by the country's leadership, will launch missiles fully automatic or if there is still a human approval process involved, with newer sources suggesting the latter.

The "Schlesinger Doctrine" is the name, given by the press, to a major re-alignment of United States nuclear strike policy that was announced in January 1974 by the US Secretary of Defense, James Schlesinger. It outlined a broad selection of counterforce options against a wide variety of potential enemy actions, a major change from earlier SIOP policies of the Kennedy and Johnson eras that focused on Mutually Assured Destruction and typically included only one or two "all-out" plans of action that used the entire U.S. nuclear arsenal in a single strike. A key element of the new plans were a variety of limited strikes solely against enemy military targets while ensuring the survivability of the U.S. second-strike capability, which was intended to leave an opening for a negotiated settlement.

Nuclear escalation is the concept of a conflict escalating from conventional warfare to nuclear warfare.

References

- Elbridge Colby; Michael S. Gerson, eds. (2013). Strategic Stability: Contending Interpretations (PDF). Strategic Studies Institute and U.S. Army War College Press. ISBN 978-1-58487-562-8. OCLC 1225683283.

- Gerson, Michael S. (2013). "The origins of strategic stability: the United States and the threat of surprise attack" (PDF). In Elbridge A. Colby, Michael S. Gerson (ed.). Strategic stability: contending interpretations. Strategic Studies Institute and U.S. Army War College Press. pp. 1–46. ISBN 978-1-58487-562-8. JSTOR resrep12086.4. OCLC 1225683283.

- Acton, James M. (2013). "Reclaiming Strategic Stability" (PDF). In Elbridge A. Colby, Michael S. Gerson (ed.). Strategic stability: contending interpretations. Strategic Studies Institute and U.S. Army War College Press. pp. 117–146. ISBN 978-1-58487-562-8. JSTOR resrep12086.7. OCLC 1225683283.

- Rojansky, Matthew (2013). "Russia and Strategic Stability" (PDF). In Elbridge A. Colby, Michael S. Gerson (ed.). Strategic stability: contending interpretations. Strategic Studies Institute and U.S. Army War College Press. pp. 295–342. ISBN 978-1-58487-562-8. JSTOR resrep12086.11. OCLC 1225683283.

- Trenin, Dmitri. "Strategic Stability in the Changing World" (PDF). carnegieendowment.org. Carnegie Moscow Center. Retrieved March 21, 2019.

- Steinbruner, John D. (September 1978). "National Security and the Concept of Strategic Stability". Journal of Conflict Resolution. 22 (3): 411–428. doi:10.1177/002200277802200303. eISSN 1552-8766. ISSN 0022-0027. S2CID 154869775.

- Sechser, Todd S.; Narang, Neil; Talmadge, Caitlin (22 August 2019). "Emerging technologies and strategic stability in peacetime, crisis, and war". Journal of Strategic Studies. 42 (6): 727–735. doi:10.1080/01402390.2019.1626725. eISSN 1743-937X. ISSN 0140-2390.

- Arbatov, Alexey (4 December 2020). "Nuclear Deterrence: A Guarantee for or Threat to Strategic Stability?". NL ARMS (PDF). T.M.C. Asser Press. pp. 65–86. doi:10.1007/978-94-6265-419-8_5. eISSN 2452-235X. ISSN 1387-8050.

- Dall'Agnol, Augusto C.; Cepik, Marco (18 June 2021). "The demise of the INF Treaty: a path dependence analysis". Revista Brasileira de Política Internacional. 64 (2): 1–19. doi: 10.1590/0034-7329202100202 . ISSN 1983-3121.

- Brustlein, Corentin (November 2018). "The Erosion of Strategic Stability and the Future of Arms Control in Europe" (PDF). IFRI Proliferation Papers. 60. Institut français des relations internationales. ISBN 9782365679329.