Related Research Articles

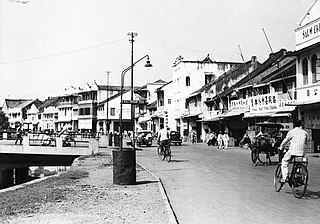

Batavia was the capital of the Dutch East Indies. The area corresponds to present-day Jakarta, Indonesia. Batavia can refer to the city proper or its suburbs and hinterland, the Ommelanden, which included the much larger area of the Residency of Batavia in the present-day Indonesian provinces of Jakarta, Banten and West Java.

Eduard Douwes Dekker, better known by his pen name Multatuli, was a Dutch writer best known for his satirical novel Max Havelaar (1860), which denounced the abuses of colonialism in the Dutch East Indies. He is considered one of the Netherlands' greatest authors.

Sugar plantations in the Caribbean were a major part of the economy of the islands in the 18th, 19th, and 20th centuries. Most Caribbean islands were covered with sugar cane fields and mills for refining the crop. The main source of labor, until the abolition of chattel slavery, was enslaved Africans. After the abolition of slavery, indentured laborers from India, China, Portugal and other places were brought to the Caribbean to work in the sugar industry. These plantations produced 80 to 90 percent of the sugar consumed in Western Europe, later supplanted by European-grown sugar beet.

The Cultivation System was a Dutch government policy from 1830–1870 for its Dutch East Indies colony. Requiring a portion of agricultural production to be devoted to export crops, it is referred to by Indonesian historians as tanam paksa.

Wolter Robert Baron van Hoëvell was a Dutch minister, politician, reformer, and writer. Born into nobility and trained in the Dutch Reformed Church, he worked for eleven years as a minister in the Dutch East Indies. He led a Malay-speaking congregation, engaged in scholarly research and cultural activities, and became an outspoken critic of Dutch colonialism. His activism culminated when he acted as one of the leaders of a short-lived protest in 1848. During the event, a multi-ethnic group of Batavian inhabitants presented their grievances to the local government. As a result of his leadership in the protest, van Hoëvell was forced to resign his position in the Indies.

Totok is an Indonesian term of Javanese origin, used in Indonesia to refer to recent migrants of Arab, Chinese, or European origins. In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries it was popularised among colonists in Batavia, who initially coined the term to describe the foreign born and new immigrants of "pure blood" – as opposed to people of mixed indigenous and foreign descent, such as the Peranakan Arabs, Chinese or Europeans.

The Dutch East Indies, also known as the Netherlands East Indies, was a Dutch colony with territory mostly comprising the modern state of Indonesia, which declared independence on 17 August 1945. Following the Indonesian War of Independence, Indonesia and the Netherlands made peace in 1949. In the Anglo-Dutch Treaty of 1824, the Dutch ceded the governorate of Dutch Malacca to Britain, leading to its eventual incorporation into Malacca (state) of modern Malaysia.

The 1740 Batavia massacre was a massacre and pogrom of ethnic Chinese residents of the port city of Batavia, Dutch East Indies, in the Dutch East Indies. It was carried out by European soldiers of the Dutch East India Company and allied members of other Batavian ethnic groups. The violence in the city lasted from 9 October 1740, until 22 October, with minor skirmishes outside the walls continuing late into November that year. Historians have estimated that at least 10,000 ethnic Chinese were massacred; just 600 to 3,000 are believed to have survived.

Sugar production in the Danish West Indies, now the United States Virgin Islands, was an important part of the economy of the islands for over two hundred years. Long before the islands became part of the United States in 1917, the islands, in particular the island of Saint Croix, was exploited by the Danish from the early 18th century, and by 1800 over 30,000 acres were under cultivation, earning Saint Croix a reputation as the "Garden of the West Indies". Since the closing of the last sugar factory on Saint Croix in 1966, the industry has become only a memory.

The Liberal Period refers to the economic policies instituted in the Dutch East Indies from the mid-19th century.

The economic history of Indonesia is shaped by its geographic location, its natural resources, as well as its people that inhabited the archipelago that today formed the modern nation-state of the Republic of Indonesia. The foreign contact and international trade with foreign counterparts had also shaped and sealed the fate of Indonesian archipelago, as Indians, Chinese, Arabs, and eventually European traders reached the archipelago during the Age of Exploration and participated in the spice trade, war and conquest.

John Ricus Couperus was a Dutch lawyer, member of the Council of Justice in Padang, member of the High Military Court of the Dutch East Indies and the landheer of Tjikopo. He was also the father of the Dutch writer Louis Couperus and knight in the Order of the Netherlands Lion.

The Suikerbond was a trade union for European workers in the sugar industry in the Dutch East Indies. The organization was founded on 14 March 1907 in Surabaya, as the Bond van Geëmployeerden in de Suikerindustrie in Nederlandsch-Indië. One of the two strongest unions for Europeans, in the early 1920s, during a wave of strikes by factory workers, the Suikerbond had been "bought off" by the sugar industry which had raised wages for European workers. In 1921 the organization founded its own newspaper, De Indische Courant, which was run by the union's president, W. Burger, and appears in two editions on the island of Java; initially leaning social-democratic, under pressure from union members a more conservative editor in chief was installed. By 1922 the organization numbered over 3800 members and had a strike fund of a half a million guilders.

The French and British interregnum in the Dutch East Indies of the Dutch East Indies took place between 1806 and 1816. The French ruled between 1806 and 1811, while the British took over for 1811 to 1816 and transferred its control back to the Dutch in 1816.

The Haarlemmermeer class was a class of nine gunvessels of the Royal Netherlands Navy. The class was a failure because of its extreme susceptibility to dry rot.

PT Perkebunan Nusantara IX (Persero) (abbreviated as PTPN IX), is an Indonesian state-owned agricultural company for the cultivation and processing of sugar cane, rubber, tea and coffee. Its own plantations and factories are located at locations in Central Java.

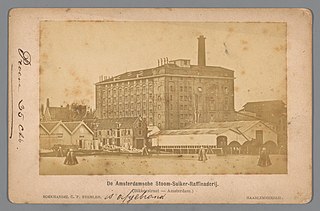

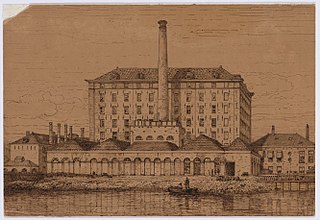

The Amsterdamsche Stoom Suikerraffinaderij was a big Dutch sugar refining company. It produced white sugar by refining raw sugar from sugar cane. The company existed from 1833 to 1875 and was one of the most important industrial companies of Amsterdam.

The Nederlandsche Suikerraffinaderij NV (NSR) was an Amsterdam sugar refining company that refined sugar cane to produce white sugar and other sugar products. After its closure, its main sugar refinery became part of the Amstel Suikerraffinaderij and later was part of the Wester Suikerraffinaderij.

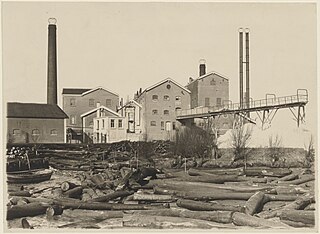

Dordrecht Sugar Factory was an early Dutch beet sugar factory, built in 1861. It closed down in 1909 and has since been completely demolished.

Estate Rust-Op-Twist, situated near Christiansted on the island of Saint Croix in the U.S. Virgin Islands, is a former colonial sugar plantation. It was a hub of sugar production from 1755 until the early 1900s, and is currently listed on the US National Register of Historic Places.

References

Citations

- ↑ Roger Knight 2014, p. 27.

- ↑ Money 1861, p. 114.

- ↑ Suikerfabrieken 1857, p. 6.

- ↑ Suikerfabrieken 1857, p. 3.

- ↑ Suikerfabrieken 1857, p. 4.

- ↑ Money 1861, p. 319.

- ↑ Money 1861, p. 320.

- ↑ Boys 1892, p. 61.

- ↑ Handelingen 1853, p. 318.

- ↑ Suikerwet 1870, p. 1.

- ↑ Suikerwet 1870, p. 5.

- ↑ Suikerwet 1870, p. 10.

- ↑ Suikerwet 1870, p. 11.

- ↑ Suikerwet 1870, p. 12.

- ↑ Bosma 2013, p. 120.

Bibliography

- Money, J.W.B. (1861), Java: Or, How to Manage a Colony, vol. I, Hurst and Blackett, London

- Stukken betreffende het onderzoek der commissie voor de opname der verschillende Suikerfabrieken op Java, 1857

- Boys, Henry Scott (1892), Some notes on Java and its administration by the Dutch, OL 24154014M

- Verslag der handelingen, Netherlands. Staten-Generaal, 1853

- De nieuwe suikerwet, Staatsblad, 1870

- Roger Knight, G. (2014), Sugar, Steam and Steel: The Industrial Project in Colonial Java, 1830-1885, University of Adelaide Press, ISBN 9781922064998

- Bosma, Ulbe (2013), The Sugar Plantation in India and Indonesia: Industrial Production, 1770-2010, Cambridge University Press