Related Research Articles

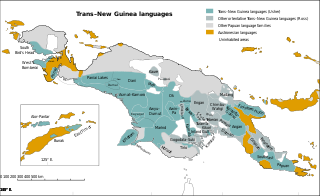

Trans–New Guinea (TNG) is an extensive family of Papuan languages spoken on the island of New Guinea and neighboring islands, a region corresponding to the country Papua New Guinea as well as parts of Indonesia.

The Papuan languages are the non-Austronesian languages spoken on the western Pacific island of New Guinea, as well as neighbouring islands in Indonesia, Solomon Islands, and East Timor. It is a strictly geographical grouping, and does not imply a genetic relationship.

Tayap is an endangered Papuan language spoken by fewer than 50 people in Gapun village of Marienberg Rural LLG in East Sepik Province, Papua New Guinea. It is being replaced by the national language and lingua franca Tok Pisin.

The Torricelli languages are a family of about fifty languages of the northern Papua New Guinea coast, spoken by about 80,000 people. They are named after the Torricelli Mountains. The most populous and best known Torricelli language is Arapesh, with about 30,000 speakers.

The Kwomtari–Fas languages, often referred to ambiguously as Kwomtari, are an apparently spurious language family proposal of six languages spoken by some 4,000 people in the north of Papua New Guinea, near the border with Indonesia. The term "Kwomtari languages" can also refer to one of the established families that makes up this proposal.

The Border or Upper Tami languages are an independent family of Papuan languages in Malcolm Ross's version of the Trans–New Guinea proposal.

Western Pantar, sometimes referred to by the name of one of its dialects, Lamma, is a Papuan language spoken in the western part of Pantar island in the Alor archipelago of Indonesia. Western Pantar is spoken widely in the region by about 10,000 speakers. Although speakers often use Malay in political, religious, and educational contexts, Western Pantar remains the first language of children of the region, and is acquired to some extent by immigrants.

Gogodala is a Papuan language of Papua New Guinea. Its closest relative is the Ari language.

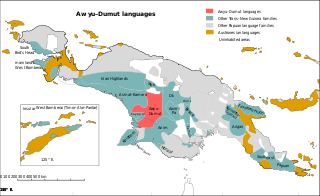

The Greater Awyu or Digul River languages, known in earlier classifications with more limited scope as Awyu–Dumut (Awyu–Ndumut), are a family of perhaps a dozen Trans–New Guinea languages spoken in eastern West Papua in the region of the Digul River. Six of the languages are sufficiently attested for a basic description; it is not clear how many of the additional names may be separate languages.

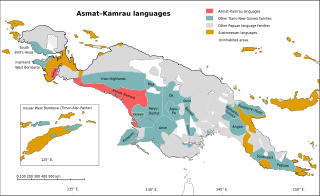

The Asmat – Kamrau Bay languages are a family of a dozen Trans–New Guinea languages spoken by the Asmat and related peoples in southern Western New Guinea. They are believed to be a recent expansion along the south coast, as they are all closely related, and there is little differentiation in their pronouns.

The Kayagar languages are a small family of four closely related Trans–New Guinea languages spoken around the Cook River in Province of South Papua, Indonesia:

The Pauwasi languages are a likely family of Papuan languages, mostly in Indonesia. The subfamilies are at best only distantly related. The best described Pauwasi language is Karkar, across the border in Papua New Guinea. They are spoken around the headwaters of the Pauwasi River in the Indonesian-PNG border region.

The Dani or Baliem Valley languages are a family of clearly related Trans–New Guinea languages spoken by the Dani and related peoples in the Baliem Valley in the Highland Papua, Indonesia. Foley (2003) considers their Trans–New Guinea language group status to be established. They may be most closely related to the languages of Paniai Lakes, but this is not yet clear. Capell (1962) posited that their closest relatives were the Kwerba languages, which Ross (2005) rejects.

The Duna–Pogaya (Duna–Bogaia) languages are a proposed small family of Trans–New Guinea languages in the classification of Voorhoeve (1975), Ross (2005) and Usher (2018), consisting of two languages, Duna and Bogaya, which in turn form a branch of the larger Trans–New Guinea family. Glottolog, which is based largely on Usher, however finds the connections between the two languages to be tenuous, and the connection to TNG unconvincing.

The Gogodala–Suki or Suki – Aramia River languages are a small language family of Papua New Guinea, spoken in the region of the Aramia River.

The Mombum languages, also known as the Komolom or Muli Strait languages, are a pair of Trans–New Guinea languages, Mombum (Komolom) and Koneraw, spoken on Komolom Island just off Yos Sudarso Island, and on the southern coast of Yos Sudarso Island, respectively, on the southern coast of New Guinea. Komolom Island is at the southern end of the Muli Strait.

Momuna (Momina), also known as Somahai, is a Papuan language spoken in Yahukimo Regency, Highland Papua and Asmat Regency, South Papua, Indonesia.

West Bird's Head languages are a small family of poorly documented Papuan languages spoken on the Bird's Head Peninsula of New Guinea.

Duriankari, or Duriankere, is a possibly extinct Papuan language of Indonesian Papua. It is associated with the village of Duriankari at the southern tip of the island of Salawati, which is part of the Raja Ampat Archipelago and is adjacent to the Bird's Head Peninsula of the West Papuan mainland.

Proto-Trans–New Guinea is the reconstructed proto-language ancestral to the Trans–New Guinea languages. Reconstructions have been proposed by Malcolm Ross and Andrew Pawley.

References

- ↑ Suki at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015) (subscription required)

- 1 2 Wurm, S.A. (1977)

- ↑ United Nations in Papua New Guinea (2018). "Papua New Guinea Village Coordinates Lookup". Humanitarian Data Exchange. 1.31.9.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Voorhoeve, C.L. (1970)

- 1 2 Gordon, Raymond G., Jr. (2005)

- ↑ Capell, A. (1969)

- ↑ The New Testament in Suki (1981)