Analysis

In 1981, film historian Vito Russo wrote that "only twice has a serious American film dealt with homosexuality as a family issue or even suggested that homosexuals might be someone's children." He noted the films as being this one and Bloodbrothers as the other. He continued on saying that in this film, the "homosexuality of Rita's son is seen only in terms of how the revelation affects her present mid-life crisis, as one more token of her failure as a wife and mother." Russo also points out that Bobby moves to Amsterdam with his lover and cuts off contact with his parents "until they can deal with him as he is; he turns their inability to see him as a whole person into their problem, not his problem." [1]

Author Noah Tsika argues that "while its stridency would seem to make it an ideal candidate for camp status, the film is actually closer in tone to queer tragedy and contains thematic elements so profoundly recognizable that they cannot be recuperated as comedy; in particular, the film's motif of maternal rejection – so believably embodied by a brittle Joanne Woodward – makes this film an uncomfortably realistic account of American family life." [2]

Critical reception

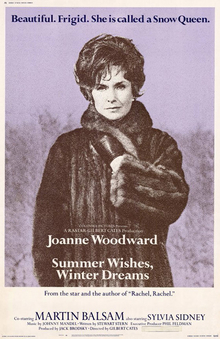

Ruth Gilbert wrote in New York Magazine that the film is "a lovely, intense and deeply affecting drama of emotional crisis, with a fine performance by Joanne Woodward in a searing portrait of a middle-aged woman, forced, on her mother's death, to face her own pattern of living. Martin Balsam and Sylvia Sidney are equally fine in a film that matters and will remain in your heart." [3]

Film critic Nora Sayre said "from time to time, there's a movie that makes you feel like a moderate heel; although you respect the talents and the themes, it's not possible to respond emotionally, even though you might want to." She goes on to note that the "alternate folksiness and banality of the script means this movie is a forlorn waste of two fine character actors." [4]

Variety Magazine wrote that "performances by Woodward, Balsam and Sidney are first-rate, and they create genuinely tender moments; but only those past 40 and approaching 50 or more are likely to feel the depth." [5] Film historian Richard Schickel offered praise for Woodward's performance, writing "there is no more authentic, believably feminine spirit on the screen today; she is brittle, cold, hysterical, but above all a woman who knows that she is lost and is in desperate search of herself. It is a lovely performance, almost matched by Balsam." [6]

Critic Steven Mears opined that "for much of the film's first half, Balsam stands in the background of his scenes, fecklessly trying to comfort his unresponsive wife or broker peace with her relatives; pudgy, his thinning hair combed over with characteristic optimism and his conversation rife with hackneyed pleasantries, Harry is hardly what Rita as a warm-blooded farm girl imagined her romantic future held." [7]