The swastika is an ancient religious and cultural symbol, predominantly found in various Eurasian cultures, as well as some African and American ones. In the Western world, it is more widely recognized as a symbol of the German Nazi Party who appropriated it from Asian cultures starting in the early 20th century. The appropriation continues with its use by neo-Nazis around the world. The swastika never stopped being used as a symbol of divinity and spirituality in Indian religions, including Hinduism, Buddhism, and Jainism. It generally takes the form of a cross, the arms of which are of equal length and perpendicular to the adjacent arms, each bent midway at a right angle.

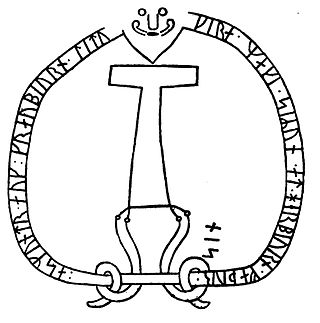

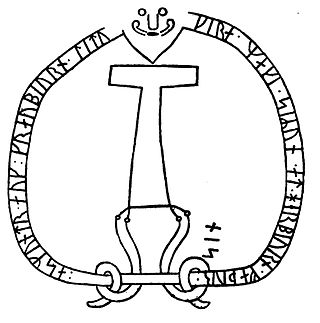

Mjölnir is the hammer of the thunder god Thor in Norse mythology, used both as a devastating weapon and as a divine instrument to provide blessings. The hammer is attested in numerous sources, including the 11th century runic Kvinneby amulet, the Poetic Edda, a collection of eddic poetry compiled in the 13th century, and the Prose Edda, a collection of prose and poetry compiled in the 13th century. The hammer was commonly worn as a pendant during the Viking Age in the Scandinavian cultural sphere, and Thor and his hammer occur depicted on a variety of objects from the archaeological record. Today the symbol appears in a wide variety of media and is again worn as a pendant by various groups, including adherents of modern Heathenry.

Thor is a prominent god in Germanic paganism. In Norse mythology, he is a hammer-wielding god associated with lightning, thunder, storms, sacred groves and trees, strength, the protection of humankind, hallowing, and fertility. Besides Old Norse Þórr, the deity occurs in Old English as Thunor, in Old Frisian as Thuner, in Old Saxon as Thunar, and in Old High German as Donar, all ultimately stemming from the Proto-Germanic theonym *Þun(a)raz, meaning 'Thunder'.

A bracteate is a flat, thin, single-sided gold medal worn as jewelry that was produced in Northern Europe predominantly during the Migration Period of the Germanic Iron Age. Bracteate coins are also known from the medieval kingdoms around the Bay of Bengal, such as Harikela and Mon city-states. The term is also used for thin discs, especially in gold, to be sewn onto clothing in the ancient world, as found for example in the ancient Persian Oxus treasure, and also later silver coins produced in central Europe during the Early Middle Ages.

A rune is a letter in a set of related alphabets known as runic alphabets native to the Germanic peoples. Runes were used to write Germanic languages before they adopted the Latin alphabet, and for specialised purposes thereafter. In addition to representing a sound value, runes can be used to represent the concepts after which they are named (ideographs). Scholars refer to instances of the latter as Begriffsrunen. The Scandinavian variants are also known as fuþark, or futhark; this name is derived from the first six letters of the script, ⟨ᚠ⟩, ⟨ᚢ⟩, ⟨ᚦ⟩, ⟨ᚨ⟩/⟨ᚬ⟩, ⟨ᚱ⟩, and ⟨ᚲ⟩/⟨ᚴ⟩, corresponding to the Latin letters ⟨f⟩, ⟨u⟩, ⟨þ⟩/⟨th⟩, ⟨a⟩, ⟨r⟩, and ⟨k⟩. The Anglo-Saxon variant is known as futhorc, or fuþorc, due to changes in Old English of the sounds represented by the fourth letter, ⟨ᚨ⟩/⟨ᚩ⟩.

Germanic paganism or Germanic religion refers to the traditional, culturally significant religion of the Germanic peoples. With a chronological range of at least one thousand years in an area covering Scandinavia, the British Isles, modern Germany, the Netherlands, and at times other parts of Europe, the beliefs and practices of Germanic paganism varied. Scholars typically assume some degree of continuity between Roman-era beliefs and those found in Norse paganism, as well as between Germanic religion and reconstructed Indo-European religion and post-conversion folklore, though the precise degree and details of this continuity are subjects of debate. Germanic religion was influenced by neighboring cultures, including that of the Celts, the Romans, and, later, by the Christian religion. Very few sources exist that were written by pagan adherents themselves; instead, most were written by outsiders and can thus present problems for reconstructing authentic Germanic beliefs and practices.

The Elder Futhark, also known as the Older Futhark, Old Futhark, or Germanic Futhark, is the oldest form of the runic alphabets. It was a writing system used by Germanic peoples for Northwest Germanic dialects in the Migration Period. Inscriptions are found on artifacts including jewelry, amulets, plateware, tools, and weapons, as well as runestones, from the 1st to the 9th centuries.

A runic inscription is an inscription made in one of the various runic alphabets. They generally contained practical information or memorials instead of magic or mythic stories. The body of runic inscriptions falls into the three categories of Elder Futhark, Anglo-Frisian Futhorc and Younger Futhark.

The t-rune ᛏ is named after Týr, and was identified with this god. The reconstructed Proto-Germanic name is *Tîwaz or *Teiwaz. Tiwaz rune was an ideographic symbol for a spear.

The sequence alu is found in numerous Elder Futhark runic inscriptions of Germanic Iron Age Scandinavia between the 3rd and the 8th century. The word usually appears either alone or as part of an apparent formula. The symbols represent the runes Ansuz, Laguz, and Uruz. The origin and meaning of the word are matters of dispute, though a general agreement exists among scholars that the word represents an instance of historical runic magic or is a metaphor for it. It is the most common of the early runic charm words.

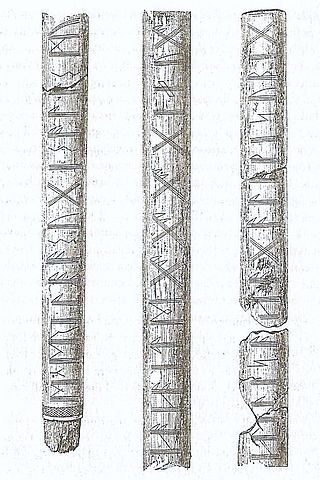

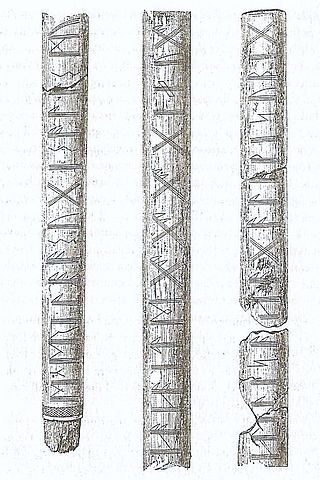

Kragehul I is a migration period lance-shaft found on Funen, Denmark. It is now in the collection of the National Museum of Denmark, Copenhagen, Denmark. The spear shaft was found in 1877 during the excavation of the classic war booty sacrificial site Kragehul on southern Funen. The site holds five deposits of military equipment from the period 200 to 475 AD. The spear shaft probably belongs to the latest deposit.

The Tjurkö Bracteates, listed by Rundata as DR BR75 and DR BR76, are two bracteates found on Tjurkö, Eastern Hundred, Blekinge, Sweden, bearing Elder Futhark runic inscriptions in Proto-Norse.

The Undley bracteate is a 5th-century bracteate found in Undley Common, near Lakenheath, Suffolk. It bears the earliest known inscription that can be argued to be in Anglo-Frisian Futhorc.

Odin is a widely revered god in Germanic paganism. Norse mythology, the source of most surviving information about him, associates him with wisdom, healing, death, royalty, the gallows, knowledge, war, battle, victory, sorcery, poetry, frenzy, and the runic alphabet, and depicts him as the husband of the goddess Frigg. In wider Germanic mythology and paganism, the god was also known in Old English as Wōden, in Old Saxon as Uuôden, in Old Dutch as Wuodan, in Old Frisian as Wêda, and in Old High German as Wuotan, all ultimately stemming from the Proto-Germanic theonym *Wōðanaz, meaning 'lord of frenzy', or 'leader of the possessed'.

Spånga Church is a church in the Spånga-Tensta borough in Stockholm, Sweden. It is part of Spånga-Kista Parish in the Diocese of Stockholm. The oldest part of the church originates from 1175–1200. Large reconstructions and enhancements took place during the 14th and 15th centuries.

Uppland Runic Inscription 1034 or U 1034 is the Rundata catalog number for a runic inscription on a runestone located at the Tensta Church, which is three kilometers northwest of Vattholma, Uppsala County, Sweden, and in the historic province of Uppland, that was carved in the late 11th or early 12th century. While the tradition of carving inscriptions into boulders began in the 4th century and lasted into the 12th century, most runestones date from the late Viking Age.

Sö 86 is the Rundata catalog number for a Viking Age memorial runic inscription located in Åby, which is about one kilometer north of Ålberga, Södermanland County, Sweden, and in the historic province of Södermanland. The inscription features a depiction of the hammer of the Norse pagan god Thor named Mjöllnir and a facial mask.

The Sæbø sword is an early 9th-century Viking sword, found in a barrow at Sæbø, Vikøyri, in Norway's Sogn region in 1825. It is now held at the Bergen Museum in Bergen, Norway.

Danish Runic Inscription 48 or DR 48 is the Rundata catalog number for a Viking Age memorial runestone from Hanning, which is about 8 km north of Skjern, Denmark. The runic inscription features a depiction of a hammer, which some have interpreted as a representation of the Norse pagan god Thor, although this interpretation is controversial.

The Læborg or Laeborg Runestone, listed as DR 26 in the Rundata catalog, is a Viking Age memorial runestone located outside of the village hall or Forsamlinghus in Læborg, which is about 3 kilometers north of Vejen, Denmark. The stone includes two depictions of the hammer of the Norse pagan god Thor.