The Levant is an approximate historical geographical term referring to a large area in the Eastern Mediterranean region of West Asia and core territory of the political term Middle East. In its narrowest sense, which is in use today in archaeology and other cultural contexts, it is equivalent to Cyprus and a stretch of land bordering the Mediterranean Sea in western Asia: i.e. the historical region of Syria, which includes present-day Israel, Jordan, Lebanon, Syria, the Palestinian territories and most of Turkey southwest of the middle Euphrates. Its overwhelming characteristic is that it represents the land bridge between Africa and Eurasia. In its widest historical sense, the Levant included all of the Eastern Mediterranean with its islands; that is, it included all of the countries along the Eastern Mediterranean shores, extending from Greece in Southern Europe to Cyrenaica, Eastern Libya in Northern Africa.

A merchant is a person who trades in commodities produced by other people, especially one who trades with foreign countries. Merchants have been known for as long as humans have engaged in trade and commerce. Merchants and merchant networks operated in ancient Babylonia, Assyria, China, Egypt, Greece, India, Persia, Phoenicia and Rome. During the European medieval period, a rapid expansion in trade and commerce led to the rise of a wealthy and powerful merchant class. The European Age of Discovery opened up new trading routes and gave European consumers access to a much broader range of goods. By the 18th century, a new type of manufacturer-merchant had started to emerge and modern business practices were becoming evident.

The history of Stockholm, capital of Sweden, for many centuries coincided with the development of what is today known as Gamla stan, the Stockholm Old Town. Stockholm's raison d'être always was to be the Swedish capital and by far the largest city in the country.

The Navigation Acts, or more broadly the Acts of Trade and Navigation, were a long series of English laws that developed, promoted, and regulated English ships, shipping, trade, and commerce with other countries and with its own colonies. The laws also regulated England's fisheries and restricted foreign—including Scottish and Irish—participation in its colonial trade. While based on earlier precedents, they were first enacted in 1651 under the Commonwealth.

The Latin Church of the Catholic Church has several dispersed populations of members in the Middle East, notably in Turkey, Cyprus and the Levant. Latin Catholics employ the Latin liturgical rites, in contrast to Eastern Catholics who fall under their respective church's patriarchs and employ distinct Eastern Catholic liturgies, while being in full communion with the worldwide Catholic Church. Latin Catholics in the Middle East are often of European descent, particularly from the medieval Crusader era and later the 20th-century colonial period.

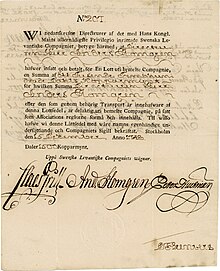

The Swedish East India Company was founded in Gothenburg, Sweden, in 1731 for the purpose of conducting trade with India, China and the Far East. The venture was inspired by the success of the Dutch East India Company and the British East India Company. This made Gothenburg a European Centre of trade in eastern products. The main goods were black pepper, spices, silk, tea, furniture, porcelain, precious stones and other distinctive luxury items. Trade with India and China saw the arrival of some new customs in Sweden. The cultural influence increased, and tea, rice, arrack and new root vegetables started appearing in Swedish homes.

The Levant Company was an English chartered company formed in 1592. Elizabeth I of England approved its initial charter on 11 September 1592 when the Venice Company (1583) and the Turkey Company (1581) merged, because their charters had expired, as she was eager to maintain trade and political alliances with the Ottoman Empire. Its initial charter was good for seven years and was granted to Edward Osborne, Richard Staper, Thomas Smith and William Garrard with the purpose of regulating English trade with the Ottoman Empire and the Levant. The company remained in continuous existence until being superseded in 1825. A member of the company was known as a Turkey Merchant.

The economic history of the Ottoman Empire covers the period 1299–1923. Trade, agriculture, transportation, and religion make up the Ottoman Empire's economy.

A chartered company is an association with investors or shareholders that is incorporated and granted rights by royal charter for the purpose of trade, exploration, or colonization, or a combination of these.

A consul is an official representative of a government who resides in a foreign country to assist and protect citizens of the consul's country, and to promote and facilitate commercial and diplomatic relations between the two countries.

Stockholm during the Age of Liberty (1718-1772) is the period in the history of Stockholm when Sweden was governed by weak kings and a strong Riksdag where the Hats and Caps were fighting each other for influence. The Age of Grand Power ended with Great Northern War, the death of Charles XII, the Stockholm treaties of 1719 and 1720.

The Marocco Company or Barbary Company was a trading company established by the Sultan of Marooco and Queen Elizabeth I of England in 1585 through a patent granted to the Earls of Warwick and Leicester, as well as forty others. When she wrote the patents, Elizabeth emphasized the value of the region's "divers Marchandize... for the use and defence" of England.

The Grill family are noted for their contribution to the Swedish iron industry and for exports of iron and copper during the 18th century. Starting as silversmiths and experts on noble metals the Grills became engaged in a wide range of businesses. After 1700 the family began its rise to prominence. They owned ironworks, while operating wharves, and importing material related to shipbuilding. The Grills benefited from mercantilist policy. With a positive balance on their account the Grills became engaged in banking, also in the Dutch Republic; around 1720 in the market for government liabilities and then mediating large credits and clearing international bills of exchange. The Grills had significant influence with the Swedish East India Company (SOIC); three members became directors of the SOIC and the Grill firm traded as members of the SOIC and privately.

Jean Abraham Grill, sometimes called Johan Abraham Grill, was a Swedish merchant, supercargo, director of the Swedish East India Company (SOIC) and ironmaster at Godegård with several factories.

Events from the year 1731 in Sweden

Levantines in Turkey or Turkish Levantines, are the descendants of Europeans who settled in the coastal cities of the Ottoman Empire to trade, especially after the Tanzimat era. Their estimated population today is around 1,000. They mainly reside in Istanbul, İzmir and Mersin. Anatolian Muslims called Levantines Frenk and tatlısu Frengi in addition to Levanten. Turkish Levantines are mostly Latin Catholics.

The economic history of Sweden's Age of Liberty examine the changes to the Swedish economy between 1718 and 1772. The economic factors that contributed to the fall of the Swedish Empire and the shift away from absolutism, as well as the legacy of the era in terms of the nation's economic history after 1772 are also noted.

Claes Grill was a Swedish merchant, factory owner and ship-owner. He was director of the Grill Trading House, one of the leading companies in the East India trade through the Swedish East India Company (SOIC). The trading house also ran a banking business and owned several ironworks in Sweden. Grill also owned several estates, was interested in natural science and had a brief and unsuccessful political career.

Adolf (Adolph) Ulric Grill was a Swedish ironworks owner and scientific collector of animals and fossils for his cabinet of curiosities at Söderfors Manor, Tierp Municipality, Uppsala County, Sweden.

The Ministry of Supply was a ministry in Sweden established in 1939. The ministry was established in order to provide a better overview of the crisis measures that the Second World War caused. The ministry dealt with administrative matters relating to general guidelines for government activities to ensure the supply within Sweden of necessities that were important to the population or production. The ministry was headed by the minister of supply. The ministry ceased to exist in 1950.