Nineveh, also known in early modern times as Kouyunjik, was an ancient Assyrian city of Upper Mesopotamia, located in the modern-day city of Mosul in northern Iraq. It is located on the eastern bank of the Tigris River and was the capital and largest city of the Neo-Assyrian Empire, as well as the largest city in the world for several decades. Today, it is a common name for the half of Mosul that lies on the eastern bank of the Tigris, and the country's Nineveh Governorate takes its name from it.

Eridu was a Sumerian city located at Tell Abu Shahrain, also Abu Shahrein or Tell Abu Shahrayn, an archaeological site in southern Mesopotamia. It is located in Dhi Qar Governorate, Iraq near the modern city of Basra. Eridu is traditionally believed to be the earliest city in southern Mesopotamia based on the Sumerian King List. Located 12 kilometers southwest of the ancient site of Ur, Eridu was the southernmost of a conglomeration of Sumerian cities that grew around temples, almost in sight of one another. The city gods of Eridu were Enki and his consort Damkina. Enki, later known as Ea, was considered to have founded the city. His temple was called E-Abzu, as Enki was believed to live in Abzu, an aquifer from which all life was believed to stem. According to Sumerian temple hymns another name for the temple of Ea/Enki was called Esira (Esirra).

"... The temple is constructed with gold and lapis lazuli, Its foundation on the nether-sea (apsu) is filled in. By the river of Sippar (Euphrates) it stands. O Apsu pure place of propriety, Esira, may thy king stand within thee. ..."

Jarmo is a prehistoric archeological site located in modern Iraq on the foothills of the Zagros Mountains. It lies at an altitude of 800 m above sea-level in a belt of oak and pistachio woodlands in the Adhaim River watershed. Excavations revealed that Jarmo was an agricultural community dating back to 7090 BC. It was broadly contemporary with such other important Neolithic sites such as Jericho in the Southern Levant and Çatalhöyük in Anatolia.

Below are notable events in archaeology that occurred in 1940.

The history of Mesopotamia ranges from the earliest human occupation in the Paleolithic period up to Late antiquity. This history is pieced together from evidence retrieved from archaeological excavations and, after the introduction of writing in the late 4th millennium BC, an increasing amount of historical sources. While in the Paleolithic and early Neolithic periods only parts of Upper Mesopotamia were occupied, the southern alluvium was settled during the late Neolithic period. Mesopotamia has been home to many of the oldest major civilizations, entering history from the Early Bronze Age, for which reason it is often called a cradle of civilization.

In the archaeology of Southwest Asia, the Late Neolithic, also known as the Ceramic Neolithic or Pottery Neolithic, is the final part of the Neolithic period, following on from the Pre-Pottery Neolithic and preceding the Chalcolithic. It is sometimes further divided into Pottery Neolithic A (PNA) and Pottery Neolithic B (PNB) phases.

Bhirrana, also Bhirdana and Birhana, is an archaeological site, located in a small village in the Fatehabad district of the north Indian state of Haryana. Bhirrana's earliest archaeological layers predates the Indus Valley civilisation times, dating to the 8th-7th millennium BCE. The site is one of the many sites seen along the channels of the seasonal Ghaggar river, thought by some to be the Rigvedic Saraswati river.

The Samarra culture is a Late Neolithic archaeological culture of northern Mesopotamia, roughly dated to between 5500 and 4800 BCE. It partially overlaps with Hassuna and early Ubaid. Samarran material culture was first recognized during excavations by German Archaeologist Ernst Herzfeld at the site of Samarra. Other sites where Samarran material has been found include Tell Shemshara, Tell es-Sawwan, and Yarim Tepe.

Lake Hamrin, is a man-made lake approximately 50 km (31 mi) north-east of Baqubah, in Iraq's Diyala Governorate. The town of Hamrin sits on the western shore of the lake, both of which are at the southern tip of the Hamrin mountains. The Hemrin Dam, which creates Lake Hamrin, was established in 1981 as an artificial dam to hold over two billion cubic metres of water. It is a source of fish and also provides water for nearby date palm orchards and other farms. In June 2008, it was reported that due to Iranian damming of the Alwand River, the lake had lost nearly 80% of its capacity.

Tell Uqair is a tell or settlement mound northeast of Babylon and about 50 miles (80 km) south of Baghdad in modern Babil Governorate, Iraq.

Tell es-Sawwan is an important Samarran period archaeological site in Saladin Province, Iraq. It is located 110 kilometres (68 mi) north of Baghdad, and south of Samarra. It lies on a 12 meter high cliff overlooking the Tigris River.

The Hassuna culture is a Neolithic archaeological culture in northern Mesopotamia dating to the early sixth millennium BC. It is named after the type site of Tell Hassuna in Iraq. Other sites where Hassuna material has been found include Tell Shemshara.

Tell Shemshara is an archaeological site located along the Little Zab in Sulaymaniyah Governorate, northeastern Iraq. The site was inundated by Lake Dukan until recently.

The art of Mesopotamia has survived in the record from early hunter-gatherer societies on to the Bronze Age cultures of the Sumerian, Akkadian, Babylonian and Assyrian empires. These empires were later replaced in the Iron Age by the Neo-Assyrian and Neo-Babylonian empires. Widely considered to be the cradle of civilization, Mesopotamia brought significant cultural developments, including the oldest examples of writing.

Tell al-Fakhar is a tell, or archaeological settlement mound, 45 kilometers southwest of the modern city of Kirkuk in Kirkuk Governorate, northeastern Iraq. Excavations were carried out at the site between 1967 and 1969 by the Directorate-General of Antiquities of Iraq. The site measures 200 by 135 metres and is 4.5 metres (15 ft) high. Excavations revealed two occupation phases that were dated to the Mitanni/Kassite and Neo-Assyrian periods, or mid-second and early-first millennia BCE. The mid-second millennium phase consisted of a large building, dubbed the "Green Palace", where an archive of circa 800 clay tablets was found. It has been suggested that the site's name was Kurruḫanni but later researchers have called this into question.

Tell Maghzaliyah, in Nineveh Governorate, Iraq, is a prehistoric fortified aceramic Mesolithic and Neolithic site located approximately 7.5 km northwest of Yarim Tepe, with which it shows some similarities. It is situated near the Abra River, a tributary of the Habur River, which eventually drains into the Euphrates River. Tell Maghzaliyah shows the development of pre-Hassuna culture. There are also numerous connections to the Jarmo culture going back to 7000 BCE.

Hakra Ware culture was a material culture which is contemporaneous with the early Harappan Ravi phase culture of the Indus Valley in Northern India and eastern-Pakistan. This culture arises in the 4th millennium with the first remnants of Hakra Ware pottery appearing near Jalilpur on the Ravi River about 80 miles (130 km) southwest of Harappa in 1972. Along with this, numerous other areas including Kunal, Dholavira, Bhirrana, Girwas, Farmana and Rakhigarhi areas of India contained Hakra Ware pottery.

Yarim Tepe is an archaeological site of an early farming settlement that goes back to about 6000 BC. It is located in the Sinjar valley some 7km southwest from the town of Tal Afar in northern Iraq. The site consists of several hills reflecting the development of the Hassuna culture, and then of the Halaf and Ubaid cultures.

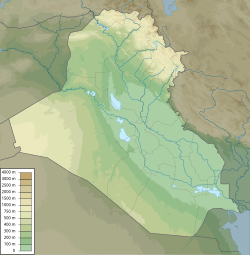

The prehistory of Mesopotamia is the period between the Paleolithic and the emergence of writing in the area of the Fertile Crescent around the Tigris and Euphrates rivers, as well as surrounding areas such as the Zagros foothills, southeastern Anatolia, and northwestern Syria.

Bestansur is a Neolithic tell, or archaeological settlement mound, located in Sulaimaniyah province, Kurdistan Regional Government, Iraq in the western Zagros foothills. The site is located on the edge of the Shahrizor Plain, 30 km to the south-east of Sulaimaniyah. It is on the UNESCO World Heritage Tentative List.