A volcano is a rupture in the crust of a planetary-mass object, such as Earth, that allows hot lava, volcanic ash, and gases to escape from a magma chamber below the surface. The process that forms volcanoes is called volcanism.

Magma is the molten or semi-molten natural material from which all igneous rocks are formed. Magma is found beneath the surface of the Earth, and evidence of magmatism has also been discovered on other terrestrial planets and some natural satellites. Besides molten rock, magma may also contain suspended crystals and gas bubbles.

Basalt is an aphanitic (fine-grained) extrusive igneous rock formed from the rapid cooling of low-viscosity lava rich in magnesium and iron exposed at or very near the surface of a rocky planet or moon. More than 90% of all volcanic rock on Earth is basalt. Rapid-cooling, fine-grained basalt is chemically equivalent to slow-cooling, coarse-grained gabbro. The eruption of basalt lava is observed by geologists at about 20 volcanoes per year. Basalt is also an important rock type on other planetary bodies in the Solar System. For example, the bulk of the plains of Venus, which cover ~80% of the surface, are basaltic; the lunar maria are plains of flood-basaltic lava flows; and basalt is a common rock on the surface of Mars.

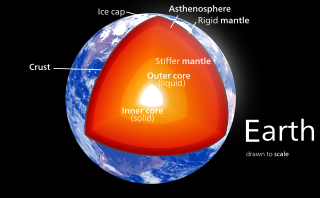

Volcanism, vulcanism, volcanicity, or volcanic activity is the phenomenon where solids, liquids, gases, and their mixtures erupt to the surface of a solid-surface astronomical body such as a planet or a moon. It is caused by the presence of a heat source, usually internally generated, inside the body; the heat is generated by various processes, such as radioactive decay or tidal heating. This heat partially melts solid material in the body or turns material into gas. The mobilized material rises through the body's interior and may break through the solid surface.

Subduction is a geological process in which the oceanic lithosphere and some continental lithosphere is recycled into the Earth's mantle at the convergent boundaries between tectonic plates. Where one tectonic plate converges with a second plate, the heavier plate dives beneath the other and sinks into the mantle. A region where this process occurs is known as a subduction zone, and its surface expression is known as an arc-trench complex. The process of subduction has created most of the Earth's continental crust. Rates of subduction are typically measured in centimeters per year, with rates of convergence as high as 11 cm/year.

A stratovolcano, also known as a composite volcano, is a typically conical volcano built up by many alternating layers (strata) of hardened lava and tephra. Unlike shield volcanoes, stratovolcanoes are characterized by a steep profile with a summit crater and explosive eruptions. Some have collapsed summit craters called calderas. The lava flowing from stratovolcanoes typically cools and solidifies before spreading far, due to high viscosity. The magma forming this lava is often felsic, having high to intermediate levels of silica, with lesser amounts of less viscous mafic magma. Extensive felsic lava flows are uncommon, but can travel as far as 8 km (5 mi).

Andesite is a volcanic rock of intermediate composition. In a general sense, it is the intermediate type between silica-poor basalt and silica-rich rhyolite. It is fine-grained (aphanitic) to porphyritic in texture, and is composed predominantly of sodium-rich plagioclase plus pyroxene or hornblende.

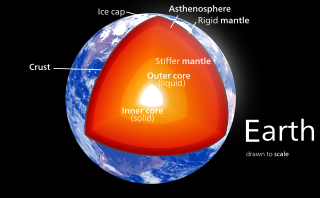

Oceanic crust is the uppermost layer of the oceanic portion of the tectonic plates. It is composed of the upper oceanic crust, with pillow lavas and a dike complex, and the lower oceanic crust, composed of troctolite, gabbro and ultramafic cumulates. The crust overlies the rigid uppermost layer of the mantle. The crust and the rigid upper mantle layer together constitute oceanic lithosphere.

A flood basalt is the result of a giant volcanic eruption or series of eruptions that covers large stretches of land or the ocean floor with basalt lava. Many flood basalts have been attributed to the onset of a hotspot reaching the surface of the Earth via a mantle plume. Flood basalt provinces such as the Deccan Traps of India are often called traps, after the Swedish word trappa, due to the characteristic stairstep geomorphology of many associated landscapes.

A volcanic arc is a belt of volcanoes formed above a subducting oceanic tectonic plate, with the belt arranged in an arc shape as seen from above. Volcanic arcs typically parallel an oceanic trench, with the arc located further from the subducting plate than the trench. The oceanic plate is saturated with water, mostly in the form of hydrous minerals such as micas, amphiboles, and serpentines. As the oceanic plate is subducted, it is subjected to increasing pressure and temperature with increasing depth. The heat and pressure break down the hydrous minerals in the plate, releasing water into the overlying mantle. Volatiles such as water drastically lower the melting point of the mantle, causing some of the mantle to melt and form magma at depth under the overriding plate. The magma ascends to form an arc of volcanoes parallel to the subduction zone.

Komatiite is a type of ultramafic mantle-derived volcanic rock defined as having crystallised from a lava of at least 18 wt% magnesium oxide (MgO). It is classified as a 'picritic rock'. Komatiites have low silicon, potassium and aluminium, and high to extremely high magnesium content. Komatiite was named for its type locality along the Komati River in South Africa, and frequently displays spinifex texture composed of large dendritic plates of olivine and pyroxene.

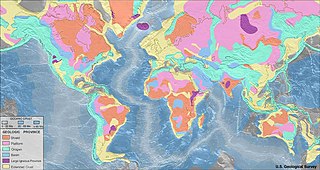

The rock cycle is a basic concept in geology that describes transitions through geologic time among the three main rock types: sedimentary, metamorphic, and igneous. Each rock type is altered when it is forced out of its equilibrium conditions. For example, an igneous rock such as basalt may break down and dissolve when exposed to the atmosphere, or melt as it is subducted under a continent. Due to the driving forces of the rock cycle, plate tectonics and the water cycle, rocks do not remain in equilibrium and change as they encounter new environments. The rock cycle explains how the three rock types are related to each other, and how processes change from one type to another over time. This cyclical aspect makes rock change a geologic cycle and, on planets containing life, a biogeochemical cycle.

The Anahim hotspot is a hypothesized hotspot in the Central Interior of British Columbia, Canada. It has been proposed as the candidate source for volcanism in the Anahim Volcanic Belt, a 300 kilometres long chain of volcanoes and other magmatic features that have undergone erosion. This chain extends from the community of Bella Bella in the west to near the small city of Quesnel in the east. While most volcanoes are created by geological activity at tectonic plate boundaries, the Anahim hotspot is located hundreds of kilometres away from the nearest plate boundary.

The geology of the Pacific Northwest includes the composition, structure, physical properties and the processes that shape the Pacific Northwest region of North America. The region is part of the Ring of Fire: the subduction of the Pacific and Farallon Plates under the North American Plate is responsible for many of the area's scenic features as well as some of its hazards, such as volcanoes, earthquakes, and landslides.

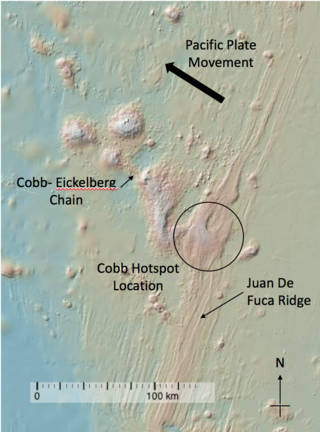

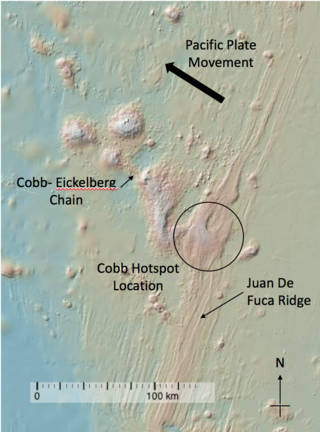

The Cobb hotspot is a marine volcanic hotspot at, which is 460 km (290 mi) west of Oregon and Washington, North America, in the Pacific Ocean. Over geologic time, the Earth's surface has migrated with respect to the hotspot through plate tectonics, creating the Cobb–Eickelberg Seamount chain. The hotspot is currently collocated with the Juan de Fuca Ridge.

Partial melting is the phenomenon that occurs when a rock is subjected to temperatures high enough to cause certain minerals to melt, but not all of them. Partial melting is an important part of the formation of all igneous rocks and some metamorphic rocks, as evidenced by a multitude of geochemical, geophysical and petrological studies.

Igneous rock, or magmatic rock, is one of the three main rock types, the others being sedimentary and metamorphic. Igneous rocks are formed through the cooling and solidification of magma or lava.

A mantle wedge is a triangular shaped piece of mantle that lies above a subducting tectonic plate and below the overriding plate. This piece of mantle can be identified using seismic velocity imaging as well as earthquake maps. Subducting oceanic slabs carry large amounts of water; this water lowers the melting temperature of the above mantle wedge. Melting of the mantle wedge can also be contributed to depressurization due to the flow in the wedge. This melt gives rise to associated volcanism on the Earth's surface. This volcanism can be seen around the world in places such as Japan and Indonesia.

A continental arc is a type of volcanic arc occurring as an "arc-shape" topographic high region along a continental margin. The continental arc is formed at an active continental margin where two tectonic plates meet, and where one plate has continental crust and the other oceanic crust along the line of plate convergence, and a subduction zone develops. The magmatism and petrogenesis of continental crust are complicated: in essence, continental arcs reflect a mixture of oceanic crust materials, mantle wedge and continental crust materials.

Emily M. Klein is a professor of geology and geochemistry at Duke University. She studies volcanic eruptions and the process of oceanic crust creation. She has spent over thirty years investigating the geology of mid-ocean ridges and identified the importance of the physical conditions of mantle melting on the chemical composition of basalt.