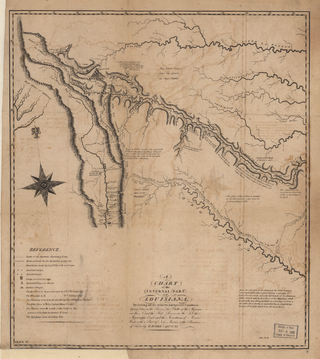

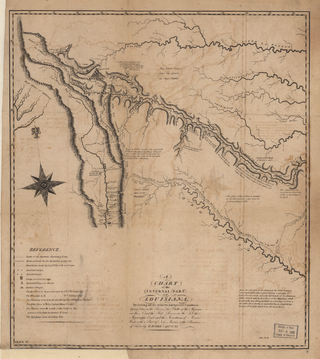

Zebulon Montgomery Pike was an American brigadier general and explorer for whom Pikes Peak in Colorado was named. As a U.S. Army officer he led two expeditions through the Louisiana Purchase territory, first in 1805–1806 to reconnoiter the upper northern reaches of the Mississippi River, and then in 1806–1807 to explore the southwest to the fringes of the northern Spanish-colonial settlements of New Mexico and Texas. Pike's expeditions coincided with other Jeffersonian expeditions, including the Lewis and Clark Expedition and the Red River Expedition in 1806.

The Pike Expedition was a military party sent out by President Thomas Jefferson and authorized by the United States government to explore the south and west of the recent Louisiana Purchase. Roughly contemporaneous with the Lewis and Clark Expedition, it was led by United States Army Lieutenant Zebulon Pike, Jr. who was promoted to captain during the trip. It was the first official American effort to explore the western Great Plains and the Rocky Mountains in present-day Colorado. Pike contacted several Native American tribes during his travels and informed them that the U.S. now claimed their territory. The expedition documented the United States' discovery of Tava which was later renamed Pikes Peak in honor of Pike. After splitting up his men, Pike led the larger contingent to find the headwaters of the Red River. A smaller group returned safely to the U.S. Army fort in St. Louis, Missouri before winter set in.

The Santa Fe Trail was a 19th-century route through central North America that connected Franklin, Missouri, with Santa Fe, New Mexico. Pioneered in 1821 by William Becknell, who departed from the Boonslick region along the Missouri River, the trail served as a vital commercial highway until 1880, when the railroad arrived in Santa Fe. Santa Fe was near the end of El Camino Real de Tierra Adentro which carried trade from Mexico City. The trail was later incorporated into parts of the National Old Trails Road and U.S. Route 66.

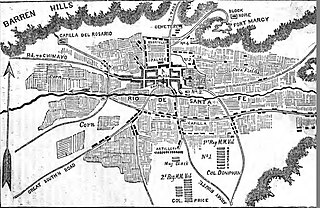

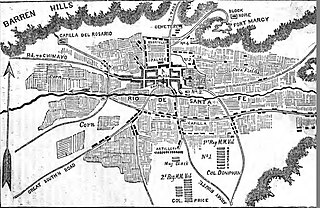

The Capture of Santa Fe, also known as the Battle of Santa Fe or the Battle of Cañoncito, took place near Santa Fe, New Mexico, the capital of the Mexican Province of New Mexico, during the Mexican–American War on 8 August through 14 August 1846. No shots were fired during the capturing of Santa Fe.

Mora or Santa Gertrudis de lo de Mora is a census-designated place in, and the county seat of, Mora County, New Mexico. It is located about halfway between Las Vegas and Taos on Highway 518, at an altitude of 7,180 feet. The Republic of Texas performed a semi-official raid on Mora in 1843. Two short battles of the Mexican–American War were fought in Mora in 1847, where U.S. troops eventually defeated the Hispano and Puebloan militia, effectively ending the Taos Revolt in the Mora Valley. The latter battle destroyed most of the community, necessitating its re-establishment.

The Old Spanish Trail is a historical trade route that connected the northern New Mexico settlements of Santa Fe, New Mexico with those of Los Angeles, California and southern California. Approximately 700 mi (1,100 km) long, the trail ran through areas of high mountains, arid deserts, and deep canyons. It is considered one of the most arduous of all trade routes ever established in the United States. Explored, in part, by Spanish explorers as early as the late 16th century, the trail was extensively used by traders with pack trains from about 1830 until the mid-1850s. The area was part of Mexico from Mexican independence in 1821 to the Mexican Cession to the United States in 1848.

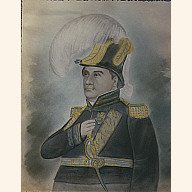

Philip St. George Cooke was a career United States Army cavalry officer who served as a Union General in the American Civil War. He is noted for his authorship of an Army cavalry manual, and is sometimes called the "Father of the U.S. Cavalry."

Comanche history In the 18th and 19th centuries the Comanche became the dominant tribe on the southern Great Plains. The Comanche are often characterized as "Lords of the Plains." They presided over a large area called Comancheria which they shared with allied tribes, the Kiowa, Kiowa-Apache, Wichita, and after 1840 the southern Cheyenne and Arapaho. Comanche power and their substantial wealth depended on horses, trading, and raiding. Adroit diplomacy was also a factor in maintaining their dominance and fending off enemies for more than a century. They subsisted on the bison herds of the Plains which they hunted for food and skins.

The Texan Santa Fe Expedition was a commercial and military expedition in 1841 by the Republic of Texas with the objective of competing with the lucrative trade conducted over the Santa Fe Trail and the ulterior motive of annexing to Texas the eastern one-half of New Mexico, then a province of Mexico. The expedition was unofficially initiated by the president of Texas, Mirabeau B. Lamar. The initiative was a major component of Lamar's ambitious plan to turn the fledgling republic into a continental power, which the president believed had to be achieved as quickly as possible to stave off the growing movement demanding the annexation of Texas to the United States. Lamar's administration had already started courting the New Mexicans, sending out a commissioner in 1840. Many Texans believed that the New Mexicans would be favorable to the idea of joining the Republic of Texas.

Josiah Gregg was an American merchant, explorer, naturalist, and author of Commerce of the Prairies, about the American Southwest and parts of northern Mexico. He collected many previously undescribed plants on his merchant trips and during the Mexican–American War, for which he has often been credited in botanical nomenclature. After the war he went to California, where he reportedly died of a fall from his mount due to starvation near Clear Lake on 25 February 1850, following a cross-country expedition which fixed the location of Humboldt Bay.

Manuel Armijo was a New Mexican soldier and statesman who served three times as governor of New Mexico between 1827 and 1846. He was instrumental in putting down the Revolt of 1837; he led the military forces that captured the invaders of the Texan Santa Fe Expedition; and he later surrendered to the United States in the Mexican–American War, leading to the capture of Santa Fe and occupation of New Mexico by the American army. Armijo attempted to expand Hispanic settlements and bolster the security of New Mexico by granting large acreages of land to prominent individuals. Armijo has been vilified by Americans participating in the conquest of New Mexico and some subsequent historians.

This is a timeline of the Republic of Texas, spanning the time from the Texas Declaration of Independence from Mexico on March 2, 1836, up to the transfer of power to the State of Texas on February 19, 1846.

In the history of the American frontier, pioneers built overland trails throughout the 19th century, especially between 1829 and 1870, as an alternative to sea and railroad transport. These immigrants began to settle much of North America west of the Great Plains as part of the mass overland migrations of the mid-19th century. Settlers emigrating from the eastern United States did so with various motives, among them religious persecution and economic incentives, to move from their homes to destinations further west via routes such as the Oregon, California, and Mormon Trails. After the end of the Mexican–American War in 1849, vast new American conquests again encouraged mass immigration. Legislation like the Donation Land Claim Act and significant events like the California Gold Rush further encouraged settlers to travel overland to the west.

Antonio Valverde y Cosío was the architect behind the disastrous Villasur expedition wherein the famous Spanish colonial scout José Naranjo perished.

The early history of the Arkansas Valley in Colorado began in the 1600s and to the early 1800s when explorers, hunters, trappers, and traders of European descent came to the region. Prior to that, Colorado was home to prehistoric people, including Paleo-Indians, Ancestral Puebloans, and Late prehistoric Native Americans.

Facundo Melgares was a Spanish military officer who served as both the last Spanish Governor of New Mexico and the first Mexican Governor of New Mexico. Melgares was, like most of the officials of the Spanish crown in his time, a member of the Spanish upper class. He is described as a "portly man of military demeanour" and as "a gentleman and gallant soldier".

José Antonio Vizcarra was a Mexican soldier who served as Governor of New Mexico from 1822 to 1823. While conducting an expedition against the Navajos in 1823, he was the first to record the ruins of Chaco Canyon.

The history of Cleveland County, Oklahoma refers to the history of a county in the U.S. state of Oklahoma, and the land on which it developed prior to 1907 statehood. Prior to European colonization, the land represented the edge of the domain of the Plains Indians. France and Spain both colonized and explored the area before it became part of the United States via the Louisiana Purchase. It became part of the territory of the United States and tribal land and eventually part of the U.S. state of Oklahoma.

Pedro Vial, or Pierre Vial, was a French explorer and frontiersman who lived among the Comanche and Wichita Indians for many years. He later worked for the Spanish government as a peacemaker, guide, and interpreter. He blazed trails across the Great Plains to connect the Spanish and French settlements in Texas, New Mexico, Missouri, and Louisiana. He led three Spanish expeditions that attempted unsuccessfully to intercept and halt the Lewis and Clark Expedition.

Jacob Snively (1809–1871) was a surveyor, civil engineer, officer of the Texian Army and the Army of the Republic of Texas, California 49er, miner, and Arizona pioneer.