Societal attitudes towards same-sex relationships have varied over time and place. Attitudes to male homosexuality have varied from requiring males to engage in same-sex relationships to casual integration, through acceptance, to seeing the practice as a minor sin, repressing it through law enforcement and judicial mechanisms, and to proscribing it under penalty of death. In addition, it has varied as to whether any negative attitudes towards men who have sex with men have extended to all participants, as has been common in Abrahamic religions, or only to passive (penetrated) participants, as was common in Ancient Greece and Ancient Rome. Female homosexuality has historically been given less acknowledgment, explicit acceptance, and opposition.

Section 377 is a British colonial penal code that criminalized all sexual acts "against the order of nature". The law was used to prosecute people engaging in oral and anal sex along with homosexual activity. As per a Supreme Court Judgement since 2018, the Indian Penal Code Section 377 is used to convict non-consensual sexual activities among homosexuals with a minimum of ten years’ imprisonment extended to life imprisonment. It has been used to criminalize third gender people, such as the apwint in Myanmar. In 2018, then British Prime Minister Theresa May acknowledged how the legacies of such British colonial anti-sodomy laws continue to persist today in the form of discrimination, violence, and even death.

Homosexuality in India is socially permitted by most of the traditional native philosophies of the nation, and legal rights continue to be advanced in mainstream politics and regional politics. Homosexual cohabitation is also legally permitted and comes with some legal protections and rights.

Queer theology is a theological method that has developed out of the philosophical approach of queer theory, built upon scholars such as Marcella Althaus-Reid, Michel Foucault, Gayle Rubin, Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick, and Judith Butler. Queer theology begins with the assumption that gender variance and queer desire have always been present in human history, including faith traditions and their sacred texts such as the Jewish Scriptures and the Bible. It was at one time separated into two separate theologies: gay theology and lesbian theology. Later, the two theologies would merge and expand to become the more general method of queer theology.

Anand Bakshi was an Indian poet and lyricist. He won Filmfare Award for Best Lyricist 4 times during his career. He wrote over 6000 film songs in more than 300 films.

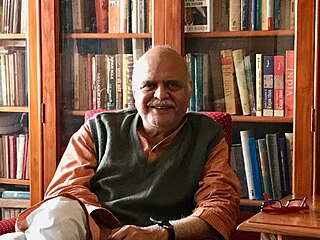

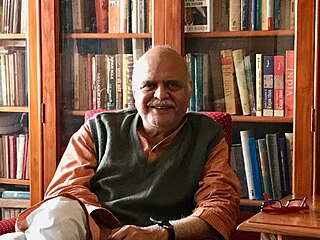

Saleem Kidwai was a medieval historian, gay rights activist, and translator. Kidwai was a professor of history at Ramjas College, University of Delhi until 1993 and thereafter an independent scholar.

Queer anarchism, or anarcha-queer, is an anarchist school of thought that advocates anarchism and social revolution as a means of queer liberation and abolition of hierarchies such as homophobia, lesbophobia, transmisogyny, biphobia, transphobia, aphobia, heteronormativity, patriarchy, and the gender binary.

Jaan is a 1996 Hindi-language action drama film directed by Raj Kanwar and produced by Ashok Ghai. The film stars Ajay Devgn, with Twinkle Khanna, Amrish Puri, Shakti Kapoor and Suresh Oberoi. It was theatrically released in United States on 31 March 1996 and India as well as other countries on 17 May 1996. The film's soundtrack was composed by Anand–Milind. Upon release, it was commercially successful, grossing ₹17.20 crore (US$2.1 million) worldwide. The film was declared a "super hit" at the box office.

Ramachandrapurapu Raj Rao is an Indian writer, poet and teacher of literature who has been described as "one of India's leading gay-rights activists". His 2003 novel The Boyfriend is one of the first gay novels to come from India. Rao was one of the first recipients of the newly established Quebec-India awards.

Riyad Vinci Wadia was an Indian independent filmmaker from Bombay, known for his short film, BOMgAY (1996), possibly the very first gay themed movie from India. Born into the filmmaking Wadia family, he inherited the production company Wadia Movietone which is known for the Fearless Nadia movies which are one of their kind in the superwoman and stunt genre when other movies of their time usually portrayed women in submissive roles. Wadia is also known for his award-winning documentary on Nadia, Fearless: The Hunterwali Story (1993), which was written about in Time magazine and made a name for Riyad at the very outset of his brief but impactful career.

LGBTQ people are well documented in various artworks and literary works of Ancient India, with evidence that homosexuality and transsexuality were accepted by the major dharmic religions. Hinduism and the various religions derived from it were not homophobic and evidence suggests that homosexuality thrived in ancient India until the medieval period. Hinduism describes a third gender that is equal to other genders and documentation of the third gender are found in ancient Hindu and Buddhist medical texts. The term "third gender" is sometimes viewed as a specifically South Asian term, and this third gender is also found throughout South Asia and East Asia.

India has a long and ancient tradition of culture associated with the LGBTQ community, with many aspects that differ markedly from modern liberal western culture.

Gaylaxy is an Indian lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (LGBT) magazine. The magazine is based in Kolkata.

Happy Ending is a 2014 Indian Hindi-language romantic comedy film written and directed by Raj Nidimoru and Krishna D.K. The film is produced by Saif Ali Khan, Dinesh Vijan and Sunil Lulla under Illuminati Films and stars Khan, Ileana D'Cruz and Govinda in the lead roles. The film was released on 21 November 2014.

Chandamama Kathalu: Volume 1 is a 2014 Indian Telugu-language anthology film directed by Praveen Sattaru and produced by Chanakya Bhooneti. The film has eight substories revolving around love. The lives of the central characters in the sub-plots get intertwined with each other. The film features an ensemble cast including Kishore, Lakshmi Manchu, Naga Shourya, Aamani, Naresh, Krishnudu, Chaitanya Krishna, Abijeet Duddala, Richa Panai, Chaitanya Krishna, and Krishneswara Rao, while Soumya Bollapragada makes a special appearance.

This is a timeline of notable events in the history of non-heterosexual conforming people of South Asian ancestry, who may identify as LGBTIQGNC, men who have sex with men, or related culturally-specific identities such as Hijra, Aravani, Thirunangaigal, Khwajasara, Kothi, Thirunambigal, Jogappa, Jogatha, or Shiva Shakti. The recorded history traces back at least two millennia.

Aligarh is a 2015 Indian Hindi- language biographical drama film directed by Hansal Mehta and written by Apurva Asrani. It stars Manoj Bajpayee and Rajkummar Rao in the lead roles.

Bindumadhav Khire is an LGBTQ+ rights activist from Pune, Maharashtra, India. He runs Samapathik Trust, an NGO which works on LGBTQ+ issues in Pune district. He founded Samapathik Trust in 2002 to cater the men having sex with men (MSM) community in Pune city. He has also written on the issues on sexuality in fictional and non-fictional forms including edited anthologies, plays, short-stories, and informative booklets.

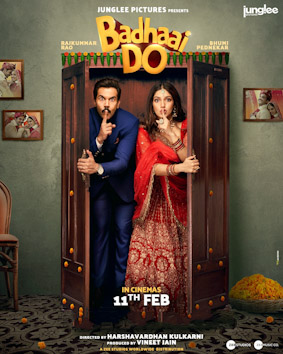

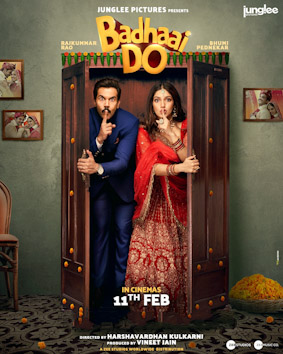

Badhaai Do is a 2022 Indian Hindi-language comedy-drama film directed by Harshavardhan Kulkarni. Produced by Junglee Pictures, it is a spiritual sequel to Badhaai Ho (2018). Depicting a couple in a lavender marriage, it stars Rajkummar Rao and Bhumi Pednekar with Gulshan Devaiah, Chum Darang, Sheeba Chaddha and Seema Pahwa in supporting roles.

The 1st Rainbow Awards ceremony was held at Rainbow Lit Fest, Gulmohar Park, New Delhi on 10 December 2023. It celebrated writers from 1 January 2022 and journalists from 1 June 2022, both until 31 May 2023.