The author, at that time, was young, twenty-four years of age, and his production bears the stamp of his youth with its good and its faulty features, of neither of which he feels ashamed. The state of things described in this book belongs to-day, in many respects, to the past, as far as England is concerned. Though not expressly stated in our recognised treatises, it is still a law of modern Political Economy that the larger the scale on which capitalistic production is carried on, the less can it support the petty devices of swindling and pilfering which characterise its early stages.

Again, the repeated visitations of cholera, typhus, small-pox and other epidemics have shown the British bourgeois the urgent necessity of sanitation in his towns and cities, if he wishes to save himself and family from falling victims to such diseases. Accordingly, the most crying abuses described in this book have either disappeared or have been made less conspicuous.

But while England has thus outgrown the juvenile state of capitalist exploitation described by me, other countries have only just attained it. France, Germany and especially America, are the formidable competitors who, at this moment – as foreseen by me in 1844 – are more and more breaking up England's industrial monopoly. Their manufactures are young as compared with those of England, but increasing at a far more rapid rate than the latter; and, curious enough, they have at this moment arrived at about the same phase of development as English manufacture in 1844. With regard to America, the parallel is indeed most striking. True, the external surroundings in which the working class is placed in America are very different, but the same economical laws are at work, and the results, if not identical in every respect, must still be of the same order. Hence we find in America the same struggles for a shorter working-day, for a legal limitation of the working-time, especially of women and children in factories; we find the truck-system in full blossom, and the cottage-system, in rural districts, made use of by the 'bosses' as a means of domination over the workers.

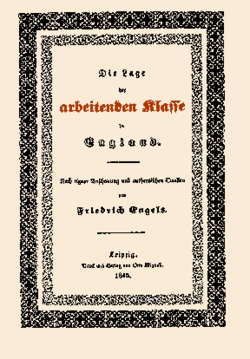

It will be hardly necessary to point out that the general theoretical standpoint of this book – philosophical, economical, political – does not exactly coincide with my standpoint of to-day. Modern international Socialism, since fully developed as a science, chiefly and almost exclusively through the efforts of Marx, did not as yet exist in 1844. My book represents one of the phases of its embryonic development; and as the human embryo, in its early stages, still reproduces the gill-arches of our fish-ancestors, so this book exhibits everywhere the traces of the descent of Modern Socialism from one of its ancestors, German philosophy. [7]

The book has been continuously reissued, and remains in print in several different editions.