Composition and publication

Sidney's Arcadia has a history that is unusually complex even for its time.

The Old Arcadia

Sidney may have begun an early draft in the late 1570s, when he was in his twenties. His own comments indicate that his purpose was humble; he asserts that he intended only to entertain his sister, Mary Herbert (Countess of Pembroke from 1577). This version is narrated in chronological order, with sets of poems separating the books from each other. It seems likely that Sidney finished this version while staying at Herbert's estate during a temporary eclipse at court in 1580.

In 1588, two years after Sidney's death, Fulke Greville appears to have appealed to Francis Walsingham to prevent an unauthorized publication of parts of the original, as we learn from a letter that also serves as evidence for the circulation of Arcadia in manuscript form:

Sir this day one Ponsonby a bookbinder in Paul's Churchyard, came to me, and told me that there was one in hand to print, Sir Philip Sidney's old Arcadia asking me if it were done with your honour's consent or any other of his friends/ I told him to my knowledge no, then he advised me to give warning of it, either to the Archbishop or Doctor Cosen, who have as he says a copy of it to peruse to that end/ Sir I am loath to renew his memory unto you, but yet in this I must presume, for I have sent my Lady your daughter at her request, a correction of that old one done 4 or 5 years since which he left in trust with me whereof there is no more copies, and fitter to be printed than that first which is so common, notwithstanding even that to be amended by a direction set down under his own hand how and why, so as in many respects especially the care of printing it is to be done with more deliberation, [1]

Sidney's original version was all but forgotten until 1907, [2] when the antiquarian Bertram Dobell discovered that a manuscript of the Arcadia he had purchased differed from published editions. Dobell subsequently acquired two other manuscripts of the old Arcadia: one from the library of the Earl of Ashburnham and one that had belonged to Sir Thomas Phillipps. This version of the Arcadia was first published in 1926, in Albert Feuillerat's edition of Sidney's collected works.

The New Arcadia

The version of the Arcadia known to the Renaissance and later periods is substantially longer than the Old Arcadia. In the 1580s, Sidney took the frame of the original story, reorganized it, and added episodes, most significantly the story of the just rebel Amphialus. The additions more than double the original story; however, Sidney had not finished the revision at the time of his death in 1586.

The New Arcadia is a romance that combines pastoral elements with a mood derived from the Hellenistic model of Heliodorus. A highly idealized version of the shepherd's life adjoins, on the other hand and not always naturally (in its literary sense), stories of jousts, political treachery, kidnappings, battles, and rapes. As published, the narrative follows the Greek model: stories are nested within each other, and different storylines are intertwined.

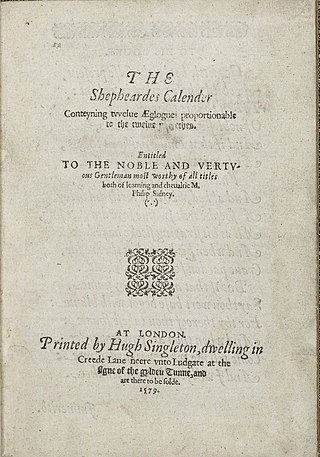

After Sidney's death, his revised Arcadia was prepared for the press and published in two differing editions. Fulke Greville, in collaboration with Matthew Gwinne and John Florio, edited and oversaw the publication of the 1590 edition, which ends in mid-scene and mid-sentence.

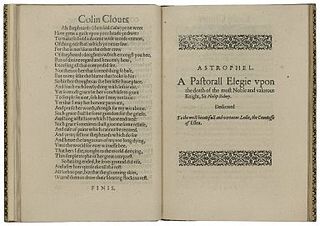

In 1593 Mary Herbert herself published an edition in which the original version supplements and concludes the part that Sidney revised. Later additions filled in gaps in the story, most notably the fifth edition of 1621, which included Sir William Alexander's attempt to work over the gap between Sidney's two versions of the story. Other continuations and developments of Sidney's story were published separately.

The hybrid editions did not efface the difference between the highly artificial, hellenized revised portion and the straightforward conclusion Sidney wrote originally. Nevertheless, it was in this form that Sidney's work entered history and reached a wide readership.

Synopsis of the Old Arcadia

Although Old Arcadia has never been greatly popular, it has entertained a small set of readers for over 400 years with its sensational treatment of sex, politics, violence, soporifics, mobs, and cross-dressing. Narrated in sprawling Renaissance prose, the romance comprises five "books or acts," organized according to the five-part structure of classical dramaturgy: exposition, action, complication, reversal, catastrophe. This hybrid structure—part prose romance and part classical drama—allows Sidney to contain the diverseness of romance within the cohesiveness of the dramatic arc. The work is often called "tragicomic" for its combination of a "serious" high plot centering on the princes and Duke Basilius's household and a "comic" low plot that centers on the steward Dametas's family. The standard modern edition of Old Arcadia, on which this synopsis is based, is edited by Jean Robertson (Clarendon: Oxford, 1973).

Book I

In Book I, the Duke of Arcadia, Basilius, journeys to the oracle at Delphos and receives a bleak prediction: his daughters will be stolen by undesirable suitors, he will be cuckolded by his wife, and his throne will be usurped by a foreign state. Hoping to preempt this fate, Basilius entrusts the Arcadian government to his loyal subject, Philanax, and retires to a pastoral lodge with his wife, Gynecia, their attractive daughters, Pamela and Philoclea, his boorish servant, Dametas, and the latter's repulsive wife and daughter, Miso and Mopsa. In a nearby city, Pyrocles and Musidorus pass the night; they are cousins, princes, and best friends, and are famous throughout Greece for their heroic exploits. Pyrocles, upon seeing a picture of Philoclea at a gallery, is overwhelmed by a passionate desire to see her in person. To that end, Pyrocles disguises himself as Cleophila, an "[Amazonian lady] going about the world to practice feats of chivalry," and heads for Basilius's pastoral lodge, accompanied by the skeptical but loyal Musidorus. Deceived by Cleophila's feminine disguise, Basilius falls in love with her, and invites her to stay with the family. While Musidorus covertly observes this meeting, he is overwhelmed by a passionate love for the elder daughter, Pamela, and decides to disguise himself as a shepherd, Dorus, in order to gain access to her. When everyone congregates in an arbor to hear the shepherds sing, a lion and bear attack the party. Cleophila kills the lion, saving Philoclea; Dorus kills the bear, saving Pamela. Cleophila's manly puissance leads Gynecia to suspect her secret male sex, while Philoclea forms an intense "sisterly" affection for Cleophila.

Book II

In Book II, the action rises as the romantic relationships become increasingly complicated, and as Basilius's retirement foments political unrest. Cleophila struggles to woo Philoclea while simultaneously placating the jealous Basilius and Gynecia. Meanwhile, Dorus, who has ingratiated himself to Dametas and entered his household as a shepherd-servant, struggles to woo Pamela, who is always accompanied by Dametas's vain and ugly daughter, Mopsa. To avoid raising suspicions that he loves Pamela, Dorus addresses all of his significant looks, sighing, singing, poetry, etc. to Mopsa, who laps it up and fails to notice the heavy-handed hints that Pamela, not Mopsa, is the object of his passion. In an extremely complicated piece of hoodwinking, Dorus reveals his identity to Pamela, proposes elopement, and is elated by the princess's willingness to flee Arcadia with him. Meanwhile, Cleophila manages to reveal his identity to Philoclea, and they declare their mutual love. Their idyll is interrupted by a mob of drunken Arcadian rabble who are angry at Basilius for neglecting his sovereign obligations. Cleophila, Basilius, Dorus and friendly shepherds slaughter much of the mob before finally subduing it. Book II ends with the establishment of the unusual love "square" in which father, mother and daughter are all violently in love with the cross-dressed Pyrocles/Cleophila, and the love triangle comprising Mopsa, Pamela and Dorus. It also begins the political theme, expanded in the fourth and fifth books, concerning the implications of negligent government.

Book III

In Book III, Musidorus tells Pyrocles of his intentions to elope with Pamela. Pyrocles despairs of his own success with Philoclea because he is under the constant surveillance of the jealous and enamored Basilius and Gynecia. Dorus's elopement strategy begins by distracting Pamela's guardians: he tricks Dametas into wasting a day on a bogus treasure hunt; he dispatches Miso by telling her Dametas is cheating on her with a woman in an adjacent village, and he leaves Mopsa up in a tree waiting for a sign from Jove. The coast cleared, Dorus and Pamela head for the nearest seaport. While resting, Dorus is overcome by her beauty and is about to rape her when they are suddenly attacked by another mob. Meanwhile, Gynecia's passion has become desperate and she threatens to expose Cleophila's identity if he does not requite her love. To distract Gynecia, Cleophila pretends to requite her love, which aggravates Basilius and Philoclea. In an ill-fated bed-trick, Cleophila promises a nocturnal assignation to both Gynecia and Basilius in a nearby cave, intending to trick the husband and wife into sleeping with each other (hoping they won't notice that the other is not Cleophila) and to enjoy a night alone with Philoclea. Book III ends with a double "climax": the attempted rape of Pamela by Dorus, and the consummated union of Pyrocles and Philoclea.

Book IV

In Book IV, Dorus and Cleophila suffer a major reversal of fortune. Dametas, Miso and Mopsa return to the lodge to find Pamela missing, and Dametas, fearing punishment for neglecting his royal ward, begins a frantic search for Pamela. Supposing her to be with her sister, Philoclea, Dametas barges into Philoclea's bed chamber and finds, of course, not Pamela, but "Cleophila," who is naked and in bed with Philoclea, and who is evidently not a woman. Dametas bolts the lovers inside and sounds the alarum. In the cave, Gynecia and Basilius, each thinking the other is Cleophila, have sex, but recognize each other in the morning. Basilius accidentally drinks a potion that Gynecia had intended for Cleophila, and dies. Gynecia becomes hysterical and self-incriminating, and offers herself up to justice as the murderer of her husband and the sovereign. Philanax, Basilius's loyal friend, arrives to investigate the duke's death and Pamela's flight, and becomes a zealous advocate for executing everyone associated with the death of Basilius. Meanwhile, Musidorus and Pamela fall captive to the attacking mob, but not before Musidorus kills and gruesomely maims several of them. Hoping for a reward for finding the fugitives, the mob heads for Basilius, but is intercepted and slaughtered by Philanax and his men, who take the captive Dorus and Pamela, who are now primary suspects in the duke's murder. Thus, Dorus (now "Palladius") joins Cleophila (now "Timopyrus") in prison. Pamela demands to be recognized as the new sovereign, but Philanax demands an interim period of investigation and burial before the succession is established. Meanwhile, the body politic erupts into a confused and "dangerous tumult" about political succession.

Book V

Book V brings the action to its catastrophe. Philanax struggles to maintain order in Arcadia, which is dangerously divided: some factions support various political climbers, others clamor for democratic government, and some call for the election of the two princes, whose good looks and military prowess had made them very popular. Philanax needs a leader capable of commanding the allegiance of the Arcadians and of bringing justice to Basilius's murderers. Luckily, the sovereign most renowned for his wise and just government, Euarchus of Thessalia, has traveled to Arcadia to visit his good friend Basilius. Euarchus is also the father of Pyrocles and uncle of Musidorus, but has no idea what they have been up to. Philanax persuades the reluctant Eurarchus to aid Arcadia by assuming authority for the present and becoming the state's "protector." The book concludes with a lengthy trial scene. Gynecia, "Palladius" and "Timopyrus" are brought forth to stand before Euarchus, who presides as judge, and Philanax, who argues on behalf of the apparently murdered Basilius. Gynecia's trial goes quickly because she, overcome by grief, wants to die as quickly as possible, and gives a false confession of intentionally poisoning her husband and sovereign. Euarchus sentences her to death by being entombed alive with Basilius. "Timopyrus" is tried next, and Philanax delivers a vituperative oratory condemning him for cross-dressing, for raping Philoclea, and for conspiring with Gynecia to murder Basilius; "Timopyrus" is acquitted of the murder charges, but is sentenced to death for raping Philoclea. "Palladius" is likewise condemned to death for attempted theft of the royal daughter, Pamela. As the convicts are escorted to their executions, a friendly compatriot of Musidorus suddenly arrives with important information. He has heard about the trial, guessed the princes' true identities, and feels Euarchus should know that he has condemned his own son and nephew to death (for various reasons, the identities of Euarchus and the princes has been hitherto obscured). At this moment of recognition, or anagnorisis, Euarchus is devastated, but decides that justice trumps kinship, and with a heavy heart confirms their death sentence. Suddenly, groans are heard from Basilius's corpse and, to the surprise and delight of all, Basilius emerges from a deep coma. All are forgiven, the princes marry the princesses, and the book thus ends with a comic reversal, or peripeteia, from justice and death to reconciliation and marriage.

Reputation and influence

Although Sidney's manuscripts of the Old Arcadia were not published until the 20th century, the New Arcadia was published in two different editions during the 16th century, and enjoyed great popularity for more than a hundred years afterwards. Sidney's book inspired a number of partial imitators, such as his niece Lady Mary Wroth's Urania , and continuations, the most famous perhaps being that by Anna Weamys. These works, however, are as close to the "precious" style of 17th-century French romance as to the Greek and chivalric models that shape Sidney's work.

William Shakespeare borrowed from Arcadia for the Gloucester subplot of King Lear ; [3] traces of the work's influence may also be found in Hamlet [4] and The Winter's Tale . [5] Other dramatizations also occurred, such as Samuel Daniel's The Queen's Arcadia, John Day's The Isle of Gulls , Beaumont and Fletcher's Cupid's Revenge , the anonymous Mucedorus play from the Shakespeare Apocrypha, and, most overtly, in James Shirley's The Arcadia .

According to John Milton in Eikonoklastes , Charles I quoted lines from the book, an excerpt termed "Pamela's Prayer", from a prayer of the heroine Pamela, as he mounted the scaffold to be executed. Although Milton praised the book as among the best of its kind, he complains of the dead king's choice of a profane text for his final prayer.

The Arcadia contains the earliest known use of the feminine personal name Pamela. Most scholars believe that Sidney simply invented the name. In the eighteenth century, Samuel Richardson named the heroine of his first novel after Sidney's Pamela. Despite this mark of continued respect, however, the rise of the novel was making works like the Arcadia obsolete. While the original is still widely read, it was already becoming a text of primary interest to historians and literary specialists.

By the beginning of the Romantic era, the grand, artificial, sometimes obstinately unwieldy style of Sidney's Arcadia had made it thoroughly alien to more modern tastes. Edmund Gosse in the EB1911 writes, "This severe censure of Euphuism may serve to remind us that hasty critics have committed an error in supposing the Arcadia of Sidney to be composed in the fashionable jargon. That was certainly not the intention of the author, and in fact the publication of the Arcadia, eleven years after that of Euphues, marks the beginning of the downfall of the popularity of the latter." [6]

In modern times, the Arcadia has been readapted for the stage. In 2013, the Old Arcadia was adapted for the stage by The University of East Anglia's Drama Department, and performed alongside Shakespeare's As You Like It as part of "The Arcadian Project". In 2018, Head Over Heels , a jukebox musical adapted from Arcadia featuring songs by The Go-Go's, opened at the Hudson Theatre. [7] [8]