Related Research Articles

Miss Jane Marple is a fictional character in Agatha Christie's crime novels and short stories. Miss Marple lives in the village of St. Mary Mead and acts as an amateur consulting detective. Often characterized as an elderly spinster, she is one of Christie's best-known characters and has been portrayed numerous times on screen. Her first appearance was in a short story published in The Royal Magazine in December 1927, "The Tuesday Night Club", which later became the first chapter of The Thirteen Problems (1932). Her first appearance in a full-length novel was in The Murder at the Vicarage in 1930, and her last appearance was in Sleeping Murder in 1976.

The Mousetrap is a murder mystery play by Agatha Christie. The Mousetrap opened in London's West End in 1952 and ran continuously until 16 March 2020, when the stage performances had to be temporarily discontinued during the COVID-19 pandemic. It then re-opened on 17 May 2021. The longest-running West End show, it has by far the longest run of any play in the world, with its 29,500th performance having taken place as of February 2024. Attendees at St Martin's Theatre often get their photo taken beside the wooden counter in the theatre foyer. As of 2022 the play has been seen by 10 million people in London.

The Hollow is a work of detective fiction by British writer Agatha Christie, first published in the United States by Dodd, Mead & Co. in 1946 and in the United Kingdom by the Collins Crime Club in November of the same year. The US edition retailed at $2.50 and the UK edition at eight shillings and sixpence (8/6). A paperback edition in the US by Dell Books in 1954 changed the title to Murder after Hours.

Five Little Pigs is a work of detective fiction by British writer Agatha Christie, first published in the US by Dodd, Mead and Company in May 1942 under the title Murder in Retrospect and in the UK by the Collins Crime Club in January 1943. The UK first edition carries a copyright date of 1942 and retailed at eight shillings while the US edition was priced at $2.00.

A Murder Is Announced is a work of detective fiction by Agatha Christie, first published in the UK by the Collins Crime Club in June 1950 and in the US by Dodd, Mead and Company in the same month. The UK edition sold for eight shillings and sixpence (8/6) and the US edition at $2.50.

4.50 from Paddington is a detective fiction novel by Agatha Christie, first published in November 1957 in the United Kingdom by Collins Crime Club. This work was published in the United States at the same time as What Mrs. McGillicuddy Saw!, by Dodd, Mead. The novel was published in serial form before the book was released in each nation, and under different titles. The US edition retailed at $2.95.

Murder in the Mews and Other Stories is a short story collection by British writer Agatha Christie, first published in the UK by Collins Crime Club on 15 March 1937. In the US, the book was published by Dodd, Mead and Company under the title Dead Man's Mirror in June 1937 with one story missing ; the 1987 Berkeley Books edition of the same title has all four stories. All of the tales feature Hercule Poirot. The UK edition retailed at seven shillings and sixpence (7/6) and the first US edition at $2.00.

Alibi is a 1928 play by Michael Morton based on The Murder of Roger Ackroyd, a 1926 novel by British crime writer Agatha Christie.

"The Witness for the Prosecution" is a short story and play by British author Agatha Christie. The story was initially published as "Traitor's Hands" in Flynn's, a weekly pulp magazine, in the edition of 31 January 1925.

Three Blind Mice and Other Stories is a collection of short stories written by Agatha Christie, first published in the US by Dodd, Mead and Company in 1950. The first edition retailed at $2.50.

Witness for the Prosecution is a play adapted by Agatha Christie from her 1925 short story "Traitor's Hands". The play opened in London on 28 October 1953 at the Winter Garden Theatre. It was produced by Sir Peter Saunders.

Sir Peter Saunders was an English theatre impresario, notable for his production of the long-running Agatha Christie murder mystery, The Mousetrap.

One, Two, Buckle My Shoe is a work of detective fiction by Agatha Christie first published in the United Kingdom by the Collins Crime Club in November 1940, and in the US by Dodd, Mead and Company in February 1941 under the title of The Patriotic Murders. A paperback edition in the US by Dell books in 1953 changed the title again to An Overdose of Death. The UK edition retailed at seven shillings and sixpence (7/6) while the United States edition retailed at $2.00.

Black Coffee is a play by the British crime-fiction author Agatha Christie (1890–1976) which was produced initially in 1930. The first piece that Christie wrote for the stage, it launched a successful second career for her as a playwright. In the play, a scientist discovers that someone in his household has stolen the formula for an explosive. The scientist calls Hercule Poirot to investigate, but is murdered just as Poirot arrives with Hastings and Inspector Japp.

And Then There Were None is a 1943 play by crime writer Agatha Christie. The play, like the 1939 book on which it is based, was originally titled and performed in the UK as Ten Little Niggers. It was also performed under the name Ten Little Indians.

Three Blind Mice is the name of a half-hour radio play written by Agatha Christie, which was later adapted into a television film, a short story, and a popular stage production.

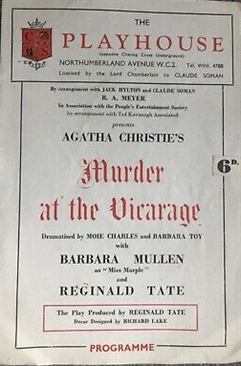

Murder at the Vicarage is a 1949 play by Moie Charles and Barbara Toy based on the 1930 novel of the same name by Agatha Christie. Christie's official biography suggests that the play was written by Christie with changes then made by Charles and Toy, presumably enough for them to claim the credit. Whatever the truth of the authorship, Christie was enthusiastic about the play and attended its rehearsals and first night.

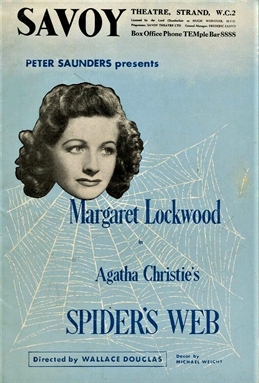

Spider's Web is a play by crime writer Agatha Christie. Spider's Web, which premiered in London’s West End in 1954, is Agatha Christie's second most successful play, having run longer than Witness for the Prosecution, which premiered in 1953. It is surpassed only by Christie's record-breaking The Mousetrap, which has run continuously since opening in the West End in 1952.

Agatha Christie (1890–1976) was an English crime novelist, short-story writer and playwright. Her reputation rests on 66 detective novels and 15 short-story collections that have sold over two billion copies, an amount surpassed only by the Bible and the works of William Shakespeare. She is also the most translated individual author in the world with her books having been translated into more than 100 languages. Her works contain several regular characters with whom the public became familiar, including Hercule Poirot, Miss Marple, Tommy and Tuppence Beresford, Parker Pyne and Harley Quin. Christie wrote more Poirot stories than any of the others, even though she thought the character to be "rather insufferable". Following the publication of the 1975 novel Curtain, Poirot's obituary appeared on the front page of The New York Times.

Agatha and the Truth of Murder is a 2018 British alternative history drama film about crime writer Agatha Christie becoming embroiled in a real-life murder case during her 11-day disappearance in 1926. Written by Tom Dalton, it depicts Christie investigating the murder of Florence Nightingale's goddaughter, Florence Nightingale Shore, which is based on real people and events, and how her involvement in this case influenced her subsequent writing.

References

- ↑ Christie, Agatha. An Autobiography. (Page 472). Collins, 1977. ISBN 0-00-216012-9

- ↑ Autobiography. (Page 473).

- ↑ Saunders, Peter. The Mousetrap Man. (Page 108) Collins, 1972. ISBN 0-00-211538-7

- ↑ Pendergast, Bruce (2004). Everyman's Guide to the Mysteries of Agatha Christie. Trafford Publishing. p. 308. ISBN 978-1-4120-2304-7.

- ↑ Saunders. (Pages 106–108)

- ↑ Saunders. (Pages 112–113)

- ↑ Morgan, Janet. Agatha Christie, A Biography. (Page 288) Collins, 1984 ISBN 0-00-216330-6.

- 1 2 Saunders. (Pages 114–115)

- ↑ Book and Magazine Collector. Issue 174. September 1998

- ↑ The Times 8 June 1951 (Page 6)

- ↑ Christie, Agatha. The Mousetrap and Other Plays (Page 174) HarperCollins, 1993. ISBN 0-00-224344-X