Soča or Isonzo is a 138-kilometre (86 mi) long river that flows through western Slovenia and northeastern Italy.

Kobarid is a settlement in Slovenia, the administrative centre of the Municipality of Kobarid.

An ossuary is a chest, box, building, well, or site made to serve as the final resting place of human skeletal remains. They are frequently used where burial space is scarce. A body is first buried in a temporary grave, then after some years the skeletal remains are removed and placed in an ossuary. The greatly reduced space taken up by an ossuary means that it is possible to store the remains of many more people in a single tomb than possible in coffins. The practice is sometimes known as grave recycling.

Pietro Badoglio, 1st Duke of Addis Abeba, 1st Marquess of Sabotino, was an Italian general during both World Wars and the first viceroy of Italian East Africa. With the fall of the Fascist regime in Italy, he became Prime Minister of Italy.

The Battle of Caporetto took place on the Italian front of World War I.

Bovec is a town in the Littoral region in northwestern Slovenia, close to the border with Italy. It is the central settlement of the Municipality of Bovec.

The First Battle of the Isonzo was fought between the armies of Italy and Austria-Hungary on the northeastern Italian Front in World War I, between 23 June and 7 July 1915.

San Biagio di Callalta is a comune (municipality) in the province of Treviso, Veneto, north-eastern Italy.

Affile is a comune (municipality) in the Metropolitan City of Rome in the Italian region of Lazio, located about 50 kilometres (31 mi) east of Rome.

The Fourth Battle of the Isonzo was fought between the armies of Kingdom of Italy and those of Austria-Hungary on the Italian Front in World War I, between 10 November and 2 December 1915.

The Exhibition of the Fascist Revolution was an art exhibition held in Rome at the Palazzo delle Esposizioni from 1932 to 1934. It was opened by Benito Mussolini on 28 October 1932 and was the longest-lasting exhibition ever mounted by the Fascist regime. Nearly four million people attended the exhibition in its two years. Intended to commemorate the revolutionaries who had taken part in the rise to power of Italian fascism, the Exhibition was supposed to be, in Mussolini's own words, "an offering of faith which the old comrades hand down to the new ones so that, enlightened by our martyrs and heroes, they may continue the heavy task."

Jevšček is a small settlement in the Municipality of Kobarid in the Littoral region of Slovenia, right on the border with Italy.

The Municipality of Kobarid is a municipality in the Upper Soča Valley in western Slovenia, near the Italian border. The seat of the municipality is the town of Kobarid.

The Asiago War Memorial is a World War I memorial located in the town of Asiago in the Province of Vicenza in the Veneto region of northeast Italy. Surrounded by mountains that were the site of several World War I battles, the monument houses the remains of over 50,000 Italian and Austro-Hungarian soldiers and is a popular destination for travelers to the region. In Italian the memorial is typically called Sacrario Militare di Asiago or Sacrario Militare del Leiten. Leiten is the name of the hill on which the memorial sits.

Giannino Castiglioni was an Italian sculptor and medallist. He worked mostly in monumental and funerary sculpture; his style was representational, and far from the modernist and avant-garde trends of the early twentieth century.

The Sacrario dei Caduti Oltremare is a World War II memorial located in the city of Bari, in the Apulia region of Southern Italy. The shrine, inaugurated in 1967, houses the remains of 75,098 Italian soldiers killed overseas in both World Wars as well as in Italy's colonial wars.

The Redipuglia War Memorial is a World War I memorial located on the Karst Plateau near the village of Fogliano Redipuglia, in the Friuli-Venezia Giulia region of northeastern Italy. It is the largest war memorial in Italy and one of the largest in the world, housing the remains of 100,187 Italian soldiers killed between 1915 and 1917 in the eleven battles fought on the Karst and Isonzo front.

The military memorial of Monte Grappa is the largest Italian military ossuary of the First World War. It is located on the summit of Monte Grappa between the provinces of Treviso and Vicenza, at 1,776 meters above sea level. Access to the memorial is via the Strada Cadorna, built by the army on the orders of General Luigi Cadorna to bring construction materials for the fortification on Monte Grappa in 1917.

The Oslavia War Memorial is an Italian monument to soldiers who fell in battle during the battles of the Isonzo, particularly those who died during the taking of Gorizia in 1916. It stands on a 150m hill in the village of Oslavia, on the outskirts of Gorizia. The hilltop was on the front line as Austro-Hungarian troops defended the salient around Gorizia during the first, third and fourth battles of the Isonzo.

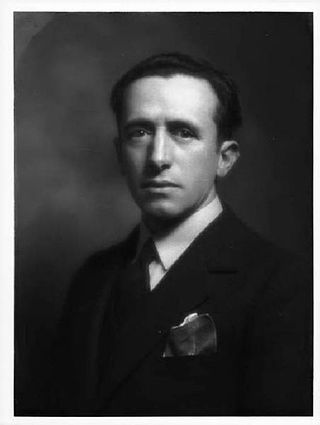

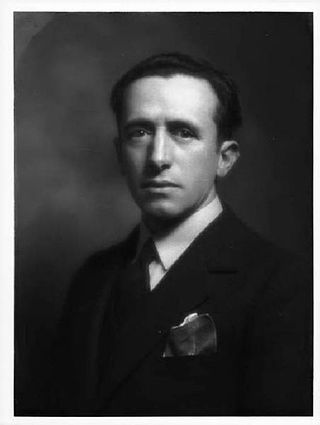

Giovanni Greppi was an Italian architect best known for having designed some of the most famous military shrines in Italy.