The French Revolution was a period of political and societal change in France that began with the Estates General of 1789, and ended with the coup of 18 Brumaire in November 1799 and the formation of the French Consulate. Many of its ideas are considered fundamental principles of liberal democracy, while its values and institutions remain central to modern French political discourse.

Georges Jacques Danton was a leading figure in the French Revolution. A modest and unknown lawyer on the eve of the Revolution, Danton became a famous orator of the Cordeliers Club and was raised to governmental responsibilities as the French Minister of Justice following the fall of the monarchy on the tenth of August 1792, and was allegedly responsible for inciting the September Massacres. He was tasked by the National Convention to intervene in the military conquest of Belgium led by French General Dumouriez. And in the Spring of 1793, he supported the foundation of a Revolutionary Tribunal and became the first president of the Committee of Public Safety.

The Society of the Friends of the Constitution, renamed the Society of the Jacobins, Friends of Freedom and Equality after 1792 and commonly known as the Jacobin Club or simply the Jacobins, was the most influential political club during the French Revolution of 1789. The period of its political ascendancy includes the Reign of Terror, during which well over 10,000 people were put on trial and executed in France, many for political crimes.

The Girondins, or Girondists, were a political group during the French Revolution. From 1791 to 1793, the Girondins were active in the Legislative Assembly and the National Convention. Together with the Montagnards, they initially were part of the Jacobin movement. They campaigned for the end of the monarchy, but then resisted the spiraling momentum of the Revolution, which caused a conflict with the more radical Montagnards. They dominated the movement until their fall in the insurrection of 31 May – 2 June 1793, which resulted in the domination of the Montagnards and the purge and eventual mass execution of the Girondins. This event is considered to mark the beginning of the Reign of Terror.

The Battle of Valmy, also known as the Cannonade of Valmy, was the first major victory by the army of France during the Revolutionary Wars that followed the French Revolution. The battle took place on 20 September 1792 as Prussian troops commanded by the Duke of Brunswick attempted to march on Paris. Generals François Kellermann and Charles Dumouriez stopped the advance near the northern village of Valmy in Champagne-Ardenne.

The sans-culottes were the common people of the lower classes in late 18th-century France, a great many of whom became radical and militant partisans of the French Revolution in response to their poor quality of life under the Ancien Régime. The word sans-culotte, which is opposed to "aristocrat", seems to have been used for the first time on 28 February 1791 by Jean-Bernard Gauthier de Murnan in a derogatory sense, speaking about a "sans-culottes army". The word came into vogue during the demonstration of 20 June 1792.

The historiography of the French Revolution stretches back over two hundred years.

There is significant disagreement among historians of the French Revolution as to its causes. Usually, they acknowledge the presence of several interlinked factors, but vary in the weight they attribute to each one. These factors include cultural changes, normally associated with the Enlightenment; social change and financial and economic difficulties; and the political actions of the involved parties. For centuries, the French society was divided into three estates or orders.

Sir Simon Michael Schama is an English historian and television presenter. He specialises in art history, Dutch history, Jewish history, and French history. He is a Professor of History and Art History at Columbia University.

Louis Antoine Léon de Saint-Just, sometimes nicknamed the Archangel of Terror, was a French revolutionary, political philosopher, member and president of the French National Convention, a Jacobin club leader, and a major figure of the French Revolution. As the youngest member elected to the National Convention, Saint-Just belonged to the Mountain faction. A steadfast supporter and close friend of Robespierre, he was swept away in his downfall during 9th Thermidor.

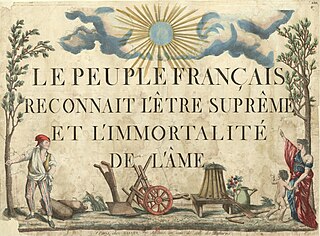

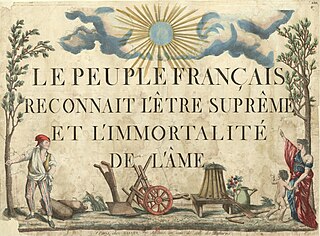

The Cult of the Supreme Being was a form of theocratic deism established by Maximilien Robespierre during the French Revolution as the intended state religion of France and a replacement for its rival, the Cult of Reason, and of Roman Catholicism. It went unsupported after the fall of Robespierre and, along with the Cult of Reason, was officially banned by First Consul Napoleon Bonaparte in 1802.

The Women's March on Versailles, also known as the October March, the October Days or simply the March on Versailles, was one of the earliest and most significant events of the French Revolution. The march began among women in the marketplaces of Paris who, on the morning of 5 October 1789, were nearly rioting over the high price of bread. The unrest quickly became intertwined with the activities of revolutionaries seeking liberal political reforms and a constitutional monarchy for France. The market women and their allies ultimately grew into a crowd of thousands. Encouraged by revolutionary agitators, they ransacked the city armory for weapons and marched on the Palace of Versailles. The crowd besieged the palace and, in a dramatic and violent confrontation, they successfully pressed their demands upon King Louis XVI. The next day, the crowd forced the king and his family to return with them to Paris. Over the next few weeks most of the French Assembly also relocated to the capital.

Norman Hampson was an English historian, Professor of History at the University of York from 1974 to 1989. He was a leading authority on the history of the French Revolution, known for challenging the orthodoxies of the dominant "French school" of revolutionary studies. He wrote an authoritative work on the social history of the Revolution.

Richard Charles Cobb was a British historian and essayist, and professor at the University of Oxford. He was the author of numerous influential works about the history of France, particularly the French Revolution. Cobb meticulously researched the Revolutionary era from a ground-level view sometimes described as "history from below".

Citizens: A Chronicle of the French Revolution is a book by the historian Simon Schama, published in 1989, the bicentenary of the French Revolution.

"The terror," declared Schama in the book, "was merely 1789 with a higher body count; violence ... was not just an unfortunate side effect ... it was the Revolution's source of collective energy. It was what made the Revolution revolutionary." In short, “From the very beginning [...] violence was the motor of revolution.” Schama considers that the French Revolutionary Wars were the logical corollary of the universalistic language of the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen, and of the universalistic principles of the Revolution which led to inevitable conflict with old-regime Europe.

William Doyle is a British historian, specialising in 18th-century France, who is most notable for his one-volume Oxford History of the French Revolution.

Maximilien François Marie Isidore de Robespierre was a French lawyer and statesman, widely recognized as one of the most influential and controversial figures of the French Revolution. Robespierre fervently campaigned for the voting rights of all men and their unimpeded admission to the National Guard. Additionally he advocated for the right to petition, the right to bear arms in self-defence, and the abolition of the Atlantic slave trade. He was a radical Jacobin leader who came to prominence as a member of the Committee of Public Safety, an administrative body of the First French Republic. His legacy has been heavily influenced by his actual or perceived participation in repression of the Revolution's opponents, but is notable for his progressive views for the time.

A People's Tragedy: The Russian Revolution, 1891–1924 is a best-selling book by the British historian Orlando Figes on the Russian Revolution and the preceding quarter of a century. Written between 1989 and 1996, it was published in 1996 and re-issued with a new introduction for the revolution's centenary in 2017.

Nietzsche: Philosopher, Psychologist, Antichrist is a book about the German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche by the philosopher Walter Kaufmann. The book, first published by Princeton University Press, was influential and is considered a classic study. Kaufmann has been credited with helping to transform Nietzsche's reputation after World War II by dissociating him from Nazism, and making it possible for Nietzsche to be taken seriously as a philosopher. However, Kaufmann has been criticized for presenting Nietzsche as an existentialist, and for other details of his interpretation.

The Freudian Fallacy, first published in the United Kingdom as Freud and Cocaine, is a 1983 book about Sigmund Freud, the founder of psychoanalysis, by the medical historian Elizabeth M. Thornton, in which the author argues that Freud became a cocaine addict and that his theories resulted from his use of cocaine. The book received several negative reviews, and some criticism from historians, but has been praised by authors critical of Freud and psychoanalysis. The work has been compared to Jeffrey Masson's The Assault on Truth (1984).