Related Research Articles

Henry VIII was King of England from 22 April 1509 until his death in 1547. Henry is best known for his six marriages, and for his efforts to have his first marriage annulled. His disagreement with Pope Clement VII about such an annulment led Henry to initiate the English Reformation, separating the Church of England from papal authority. He appointed himself Supreme Head of the Church of England and dissolved convents and monasteries, for which he was excommunicated by the pope. Henry is also known as "the father of the Royal Navy" as he invested heavily in the navy and increased its size from a few to more than 50 ships, and established the Navy Board.

The House of Tudor was a royal house of largely Welsh origin that held the English throne from 1485 to 1603. They descended from the Tudors of Penmynydd and Catherine of France. Tudor monarchs ruled the Kingdom of England and its realms, including their ancestral Wales and the Lordship of Ireland for 118 years with five monarchs: Henry VII, Henry VIII, Edward VI, Mary I and Elizabeth I. There is also a sixth Tudor monarch, Jane Grey, who disputedly reigned for nine days, in between Edward VI and Mary I. The Tudors succeeded the House of Plantagenet as rulers of the Kingdom of England, and were succeeded by the House of Stuart. The first Tudor monarch, Henry VII of England, descended through his mother from a legitimised branch of the English royal House of Lancaster, a cadet house of the Plantagenets. The Tudor family rose to power and started the Tudor period in the wake of the Wars of the Roses (1455–1487), which left the Tudor-aligned House of Lancaster extinct in the male line.

Anne Boleyn was Queen of England from 1533 to 1536, as the second wife of King Henry VIII. The circumstances of her marriage and of her execution by beheading for treason and other charges made her a key figure in the political and religious upheaval that marked the start of the English Reformation. Anne was the daughter of Thomas Boleyn, 1st Earl of Wiltshire, and his wife, Lady Elizabeth Howard, and was educated in the Netherlands and France, largely as a maid of honour to Queen Claude of France. Anne returned to England in early 1522, to marry her Irish cousin James Butler, 9th Earl of Ormond; the marriage plans were broken off, and instead she secured a post at court as maid of honour to Henry VIII's wife, Catherine of Aragon.

Jane Seymour was Queen of England as the third wife of King Henry VIII of England from their marriage on 30 May 1536 until her death the next year. She became queen following the execution of Henry's second wife, Anne Boleyn. She died of postnatal complications less than two weeks after the birth of her only child, the future King Edward VI. She was the only wife of Henry to receive a queen's funeral or to be buried beside him in St George's Chapel, Windsor Castle.

Thomas Boleyn, Earl of Wiltshire, 1st Earl of Ormond, 1st Viscount RochfordKGKB, of Hever Castle in Kent, was an English diplomat and politician who was the father of Anne Boleyn, the second wife of King Henry VIII, and was thus the maternal grandfather of Queen Elizabeth I. By Henry VIII he was made a knight of the Garter in 1523 and was elevated to the peerage as Viscount Rochford in 1525 and in 1529 was further ennobled as Earl of Wiltshire and Earl of Ormond.

This article contains information about the literary events and publications of 1533.

Thomas Howard, 3rd Duke of Norfolk, was a prominent English politician and nobleman of the Tudor era. He was an uncle of two of the wives of King Henry VIII, Anne Boleyn and Catherine Howard, both of whom were beheaded, and played a major role in the machinations affecting these royal marriages. After falling from favour in 1546, he was stripped of his Dukedom and imprisoned in the Tower of London, avoiding execution when Henry VIII died on 28 January 1547.

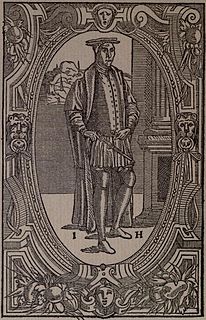

John Heywood was an English writer known for his plays, poems, and collection of proverbs. Although he is best known as a playwright, he was also active as a musician and composer, though no musical works survive. A devout Catholic, he nevertheless served as a royal servant to both the Catholic and Protestant regimes of Henry VIII, Edward VI, Mary I and Elizabeth I.

The Other Boleyn Girl (2001) is a historical novel written by British author Philippa Gregory, loosely based on the life of 16th-century aristocrat Mary Boleyn of whom little is known. Inspired by Mary's life story, Gregory depicts the annulment of one of the most significant royal marriages in English history and conveys the urgency of the need for a male heir to the throne. Much of the history is highly distorted in her account.

In common parlance, the wives of Henry VIII were the six queens consort of King Henry VIII of England between 1509 and his death in 1547. In legal terms, Henry had only three wives, because three of his marriages were annulled by the Church of England. However, he was never granted an annulment by the Pope, as he desired, for Catherine of Aragon, his first wife. Annulments declare that a true marriage never took place, unlike a divorce, in which a married couple end their union. Along with his six wives, Henry took several mistresses.

William Carey was a courtier and favourite of King Henry VIII of England. He served the king as a Gentleman of the Privy chamber, and Esquire of the Body to the King. His wife, Mary Boleyn, is known to history as a mistress of King Henry VIII and the sister of Henry's second wife, Anne Boleyn.

William Sandys, 1st Baron Sandys of the VyneKG, was an English Tudor diplomat, Lord Chamberlain and favourite of King Henry VIII.

Henry VIII and His Six Wives is a 1972 British historical film adaptation, directed by Waris Hussein, of the BBC 1970 six-part miniseries The Six Wives of Henry VIII. Keith Michell, who plays Henry VIII in the TV series, also portrays the king in the film. His six wives are portrayed by different actresses, among them Frances Cuka as Catherine of Aragon, and Jane Asher as Jane Seymour. Donald Pleasence portrays Thomas Cromwell and Bernard Hepton portrays Archbishop Thomas Cranmer, a role he had also played in the miniseries and briefly in its follow-up Elizabeth R.

Mary FitzRoy, Duchess of Richmond and Somerset, born Lady Mary Howard, was the only daughter-in-law of King Henry VIII of England, being the wife of his only acknowledged illegitimate son, Henry FitzRoy, 1st Duke of Richmond and Somerset.

Margaret Shelton was the sister of Mary Shelton, and was once thought to be a mistress of Henry VIII of England.

Henry VIII and his reign have frequently been depicted in art, film, literature, music, opera, plays, and television.

Anne Shelton née Boleyn was a sister of Thomas Boleyn, 1st Earl of Wiltshire, and one of the aunts of his daughter, Queen Anne Boleyn, the second wife of King Henry VIII.

Lady Anne Brandon, Baroness Grey of Powys was an English noblewoman, and the eldest daughter of Charles Brandon, 1st Duke of Suffolk by his second wife, Anne Browne. Anne's mother had died in 1511. In 1514, Anne's father secured a place for her at the court of Archduchess Margaret of Savoy. While Anne was abroad, her father married Mary Tudor, the widowed Queen consort of Louis XII of France and the youngest sister of Henry VIII.

Anne Gainsford, Lady Zouche was a close friend and lady-in-waiting to Queen consort Anne Boleyn.

Greg Walker is Regius professor of rhetoric and English literature at the University of Edinburgh. He is a graduate of the University of Southampton. His specialist field is the history of literature and drama in the late-medieval period and the sixteenth century.

References

- ↑ Bevington, D. (1968). Tudor Drama and Politics: A critical approach to topical meaning . Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. pp. 64–70.

- ↑ Walker, G. (1991). Plays of Persuasion: Drama and politics at the court of Henry VIII. Cambridge University Press. pp. 133–68.

- ↑ Adams, Jr., J.Q. (December 1907). "John Heywood's 'The Play of the Weather'". Modern Language Notes. 22 (8): 262. doi:10.2307/2916987. JSTOR 2916987.

- ↑ Walker, G (2005). Writing Under Tyranny: English Literature and the Henrician Reformation. Oxford University Press. pp. 100–119.

- ↑ Lines, C (Autumn 2000). "To Take on Them Judgemente: Absolutism and Debate in John Heywood's Plays". Studies in Philology. 97 (4): 425.