The morality play is a genre of medieval and early Tudor drama. The term is used by scholars of literary and dramatic history to refer to a genre of play texts from the fourteenth through sixteenth centuries that feature personified concepts alongside angels and demons, who are engaged in a struggle to persuade a protagonist who represents a generic human character toward either good or evil. The common story arc of these plays follows "the temptation, fall and redemption of the protagonist".

Sir George Buck was an English antiquarian, historian, scholar and author, who served as a Member of Parliament, government envoy to Queen Elizabeth I and Master of the Revels to King James I of England.

The Master of the Revels was the holder of a position within the English, and later the British, royal household, heading the "Revels Office" or "Office of the Revels". The Master of the Revels was an executive officer under the Lord Chamberlain. Originally he was responsible for overseeing royal festivities, known as revels, and he later also became responsible for stage censorship, until this function was transferred to the Lord Chamberlain in 1624. However, Henry Herbert, the deputy Master of the Revels and later the Master, continued to perform the function on behalf of the Lord Chamberlain until the English Civil War in 1642, when stage plays were prohibited. The office continued almost until the end of the 18th century, although with rather reduced status.

John Payne Collier was an English writer, Shakespearean critic, and forger.

Mr. William Shakespeare's Comedies, Histories, & Tragedies is a collection of plays by William Shakespeare, commonly referred to by modern scholars as the First Folio, published in 1623, about seven years after Shakespeare's death. It is considered one of the most influential books ever published.

Titivillus is a demon said to introduce errors into the work of scribes. The first reference to Titivillus by name occurred in Tractatus de Penitentia, c. 1285, by Johannes Galensis. Attribution has also been given to Caesarius of Heisterbach. Titivillus has also been described as collecting idle chat that occurs during church service, and mispronounced, mumbled or skipped words of the service, to take to Hell to be counted against the offenders.

Shakespeare's plays are a canon of approximately 39 dramatic works written by the English poet, playwright, and actor William Shakespeare. The exact number of plays as well as their classifications as tragedy, history, comedy, or otherwise is a matter of scholarly debate. Shakespeare's plays are widely regarded as among the greatest in the English language and are continually performed around the world. The plays have been translated into every major living language.

Vice is a stock character of the medieval morality plays. While the main character of these plays was representative of every human being, the other characters were representatives of personified virtues or vices who sought to win control of man's soul. While the virtues in a morality play can be seen as messengers of God, the vices were viewed as messengers of the Devil.

The Castle of Perseverance is a c. 15th-century morality play and the earliest known full-length vernacular play in existence. Along with Mankind and Wisdom, The Castle of Perseverance is preserved in the Macro Manuscript that is now housed in the Folger Shakespeare Library in Washington, D.C. The Castle of Perseverance contains nearly all of the themes found in other morality plays, but it is especially important because a stage drawing is included, which may suggest theatre in the round.

The Pilgrimage of the Soul or The Pylgremage of the Sowle was a late medieval work in English, combining prose and lyric verse, translated from Guillaume de Deguileville's Old French Le Pèlerinage de l'Âme. It circulated in manuscript in fifteenth-century England, and was among the works printed by William Caxton. One manuscript forms part of the Egerton Collection in the British Library.

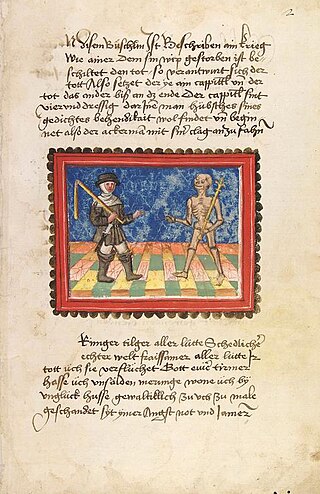

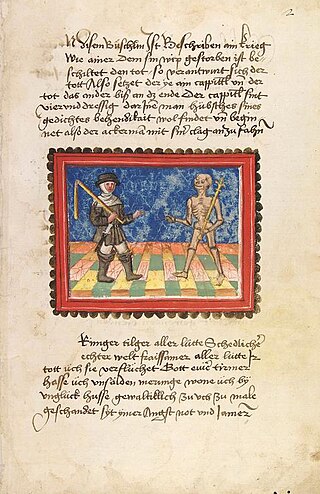

Der Ackermann aus Böhmen, also known as Der Ackermann und der Tod, is a work of prose in Early New High German by Johannes von Tepl, written around 1401. Sixteen manuscripts and seventeen early printed editions are preserved; the earliest printed version dates to 1460 and is one of the two earliest printed books in German. It is remarkable for the high level of its language and vocabulary and is considered one of the most important works of late medieval German literature.

Sinnekins are stock characters often found in medieval drama, especially morality plays. They most often occur as pairs of devilish characters who exert their perfidious influence on the main character of the drama.

Quarto is the format of a book or pamphlet produced from full sheets printed with eight pages of text, four to a side, then folded twice to produce four leaves. The leaves are then trimmed along the folds to produce eight book pages. Each printed page presents as one-fourth size of the full sheet.

Horestes is a late Tudor morality play by the English dramatist John Pickering. It was first published in 1567 and was most likely performed by Lord Rich's men as part of the Christmas revels at court that year. The play's full title is A new interlude of Vice containing the history of Horestes with the cruel revengement of his father's death upon his one natural mother. It has been proposed that John Pickering is likely to be the same person as lawyer and politician Sir John Puckering.

The Digby Conversion of Saint Paul is a Middle English miracle play of the late fifteenth century. Written in rhyme royal, it is about the conversion of Paul the Apostle. It is part of a collection of mystery plays that was bequeathed to the Bodleian Library by Sir Kenelm Digby in 1634.

John Mirk was an Augustinian Canon Regular, active in the late 14th and early 15th centuries in Shropshire. He is noted as the author of widely copied, and later printed, books intended to aid parish priests and other clergy in their work. The most famous of these, his Book of Festivals or Festial was probably the most frequently printed English book before the Reformation.

The Dering Manuscript is the earliest extant manuscript text of any play by William Shakespeare. The manuscript combines Part 1 and Part 2 of Henry IV into a single-play redaction. Scholarly consensus indicates that the manuscript was revised in the early 17th century by Sir Edward Dering, a man known for his interest in literature and theater. Dering prepared his redaction for an amateur performance starring friends and family at Surrenden Manor in Pluckley, Kent, where the manuscript was discovered in 1844. This is the earliest known instance of an amateur production of Shakespeare in England. Sourced from the 1613 fifth quarto of Part 1 and the 1600 first quarto of Part 2, the Dering Manuscript contains many textual differences from published quarto and folio editions of the plays. Dering cut nearly 3,000 lines of Shakespearean text and added some 50 lines of his own invention along with numerous minor interventions. The Dering Manuscript is currently a part of the collection at the Folger Shakespeare Library in Washington, DC.

Wisdom is one of the earliest surviving medieval morality plays. Together with Mankind and The Castle of Perseverance, it forms a collection of early English moralities called "The Macro Plays". Wisdom enacts the struggle between good and evil; as an allegory, it depicts Christ and Lucifer battling over the Soul of Man, with Christ and goodness ultimately victorious. Dating between 1460 and 1463, the play is preserved in its complete form in the Macro Manuscript, currently a part of the collection of the Folger Shakespeare Library. A manuscript fragment of the first 754 lines also belongs to the Bodleian Library. Although the author of Wisdom remains anonymous, the manuscript was transcribed and signed by a monk named Thomas Hyngman. Some scholars have suggested that Hyngman also authored the play.

The Macro Manuscript is a collection of three 15th-century English morality plays, known as the "Macro plays" or "Macro moralities": Mankind, The Castle of Perseverance, and Wisdom. So named for its 18th-century owner Reverend Cox Macro (1683–1767), the manuscript contains the earliest complete examples of English morality plays. A stage plan attached to The Castle of Perseverance is also the earliest known staging diagram in England. The manuscript is the only source for The Castle of Perseverance and Mankind and the only complete source for Wisdom. The Macro Manuscript is a part of the collection at the Folger Shakespeare Library in Washington, D.C.. For centuries, scholars have studied the Macro Manuscript for insights into medieval drama. As Clifford Davidson writes in Visualizing the Moral Life, "in spite of the fact that the plays in the manuscript are neither written by a single scribe nor even attributed to a single date, they collectively provide our most important source for understanding the fifteenth century English morality play."

The Interlude of the Student and the Girl is one of the earliest known secular plays in English, first performed c. 1300. The text is written in vernacular English, in an East Midlands dialect that suggests either Lincoln or Beverley as its origin, although its title is given in Latin. The name of its playwright is unknown. Only two scenes, with a total of 84 lines of verse in rhyming couplets, are extant and survive in a manuscript held by the British Library, dated to either the late twelfth or very early thirteenth century. Glynne Wickham provides both the original text and a rendering in modern English in his English Moral Interludes (1976). In tone and form, the interlude seems to be the closest play in English to the contemporaneous French farces, such as The Boy and the Blind Man, and is related to later English farcical plays, such as the anonymous Calisto and Melibea and John Heywood's The Foure PP. It was most likely performed by itinerant players, possibly making use of a performing dog. In Early English Stages (1981), Wickham points to the existence of this play as evidence that the old-fashioned view that comedy began in England with Gammer Gurton's Needle and Ralph Roister Doister in the 1550s is mistaken, ignoring as it does a rich tradition of medieval comic drama. He argues that the play's "command of dramatic action and of comic mood and method is so deft as to make it well-nigh unbelievable" that it was the first of its kind in England.