Related Research Articles

Deism is the philosophical position and rationalistic theology that generally rejects revelation as a source of divine knowledge, and asserts that empirical reason and observation of the natural world are exclusively logical, reliable, and sufficient to determine the existence of a Supreme Being as the creator of the universe. More simply stated, Deism is the belief in the existence of God, specifically in a creator who does not intervene in the universe after creating it, solely based on rational thought without any reliance on revealed religions or religious authority. Deism emphasizes the concept of natural theology – that is, God's existence is revealed through nature.

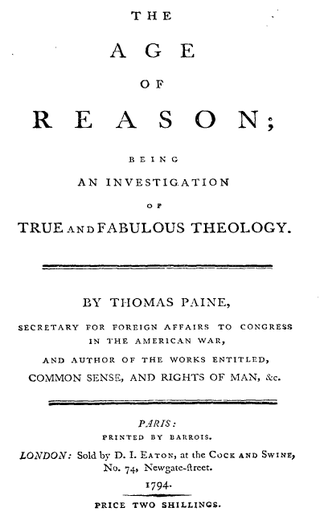

The Age of Reason; Being an Investigation of True and Fabulous Theology is a work by English and American political activist Thomas Paine, arguing for the philosophical position of deism. It follows in the tradition of 18th-century British deism, and challenges institutionalized religion and the legitimacy of the Bible. It was published in three parts in 1794, 1795, and 1807.

The Directory was the governing five-member committee in the French First Republic from 26 October 1795 until 10 November 1799, when it was overthrown by Napoleon Bonaparte in the Coup of 18 Brumaire and replaced by the Consulate. Directoire is the name of the final four years of the French Revolution. Mainstream historiography also uses the term in reference to the period from the dissolution of the National Convention on 26 October 1795 to Napoleon's coup d’état.

The Society of the Friends of the Constitution, renamed the Society of the Jacobins, Friends of Freedom and Equality after 1792 and commonly known as the Jacobin Club or simply the Jacobins, was the most influential political club during the French Revolution of 1789. The period of its political ascendancy includes the Reign of Terror, during which well over 10,000 people were put on trial and executed in France, many for political crimes.

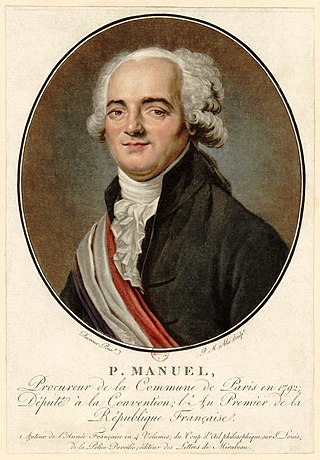

Louis Pierre Manuel was a republican French writer, municipal administrator of the police, and public prosecutor during the French Revolution who was arrested, trialled and guillotined.

Jacques René Hébert was a French journalist and the founder and editor of the extreme radical newspaper Le Père Duchesne during the French Revolution.

Louis Marie de La Révellière-Lépeaux was a deputy to the National Convention during the French Revolution. He later served as a prominent leader of the French Directory.

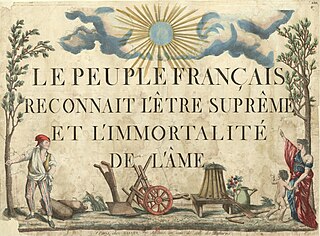

The Cult of the Supreme Being was a form of deism established in France by Maximilien Robespierre during the French Revolution. It was intended to become the state religion of the new French Republic and a replacement for Roman Catholicism and its rival, the Cult of Reason. It went unsupported after the fall of Robespierre and was officially banned by First Consul Napoleon Bonaparte in 1802.

The Cult of Reason was France's first established state-sponsored atheistic religion, intended as a replacement for Roman Catholicism during the French Revolution. After holding sway for barely a year, in 1794 it was officially replaced by the rival deistic Cult of the Supreme Being, promoted by Robespierre. Both cults were officially banned in 1802 by Napoleon Bonaparte with his Law on Cults of 18 Germinal, Year X.

The aim of a number of separate policies conducted by various governments of France during the French Revolution ranged from the appropriation by the government of the great landed estates and the large amounts of money held by the Catholic Church to the termination of Christian religious practice and of the religion itself. There has been much scholarly debate over whether the movement was popularly motivated or motivated by a small group of revolutionary radicals. These policies, which ended with the Concordat of 1801, formed the basis of the later and less radical laïcité policies.

Antoinism is a healing and Christian-oriented new religious movement founded in 1910 by Louis-Joseph Antoine (1846–1912) in Jemeppe-sur-Meuse, Seraing in Belgium. With a total of 64 temples, over forty reading rooms across the world and thousands of members, it remains the only religion established in Belgium whose notoriety and success has reached outside the country. Mainly active in France, the religious movement is characterized by a decentralized structure, simple rites, discretion and tolerance towards other faiths.

Freedom of religion in France is guaranteed by the constitutional rights set forth in the 1789 Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen.

Antoine-François Momoro was a French printer, bookseller and politician during the French Revolution. An important figure in the Cordeliers club and in Hébertisme, he is the originator of the phrase ″Unité, Indivisibilité de la République; Liberté, égalité, fraternité ou la mort″, one of the mottoes of the French Republic.

Count Charles Marie Tanneguy Duchâtel was a French politician. He was Minister of the Interior in the Cabinet of François-Pierre Guizot, losing office in the February Revolution.

Maximilien François Marie Isidore de Robespierre was a French lawyer and statesman who became one of the most widely known, influential, and controversial figures of the French Revolution.

The Universal Alliance, formerly known as Universal Christian Church and followers as Christ's Witnesses, is a Christian-oriented new religious movement founded in France in 1952 by Georges Roux, a former postman in the Vaucluse department. Roux claimed to be the reincarnation of Christ and was thus named the "Christ of Montfavet", a village on the commune of Avignon where he lived then.

Nicohlas Bonneville was a French bookseller, printer, journalist, and writer. He was also a political figure of some relevance at the time of the French Revolution and into the early years of the next century.

Lazare Nicolas Marguerite Carnot was a French mathematician, physicist, politician and a leading member of the Committee of Public Safety during the French Revolution. His military reforms, which included the introduction of mass conscription, were instrumental in transforming the French Revolutionary Army into an effective fighting force.

Irreligion in France has a long history and a large demographic constitution, with the advancement of atheism and the deprecation of theistic religion dating back as far as the French Revolution. In 2015, according to estimates, at least 29% of the country's population identifies as atheists and 63% identifies as non-religious.

The Decadary Cult or Tenth-day Cult was a semi-official religion of France during the Directory period of the French Revolution, intended to offer a non-Christian alternative after the dechristianisation of the country. It replaced the Christian Sunday worship with a quasi-religious festival on the day of rest in the 10-day week of the French Republican Calendar.

References

- Joseph Brugerette, Les cré religieuses de la revolution (Paris 1904):

- Moncure Conway, The Centenary of Theophilanthropy. The Open Court, (1897)

- Giambattista Ferrero, Disamina Filosofica de Dommi e della Morale Religiosa de Teofilantropi (Turin 1798).

- Albert Mathiez, La Théophilanthropie et le culte decadaire, 1796-1801 (Paris 1903);

- Thomas Paine, The Age of Reason

- William Hamilton Reid, The Rise and Dissolution of the Infidel Societies in this Metropolis (London, 1800):

- Maurice Tourneaux, Bibliographie de l'histoire de Paris pendant la Révolution (Paris 1890-1900).

- Maurice Tourneaux, Contributions à l'histoire religieuse de la révolution française (Paris 1907);

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain : Sollier, Joseph Francis (1913). "Theophilanthropists". In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia . Vol. 14. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain : Sollier, Joseph Francis (1913). "Theophilanthropists". In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia . Vol. 14. New York: Robert Appleton Company.