Emotions are physical and mental states brought on by neurophysiological changes, variously associated with thoughts, feelings, behavioral responses, and a degree of pleasure or displeasure. There is no scientific consensus on a definition. Emotions are often intertwined with mood, temperament, personality, disposition, or creativity.

According to the APA Dictionary of Psychology, a feeling is "a self-contained phenomenal experience"; feelings are "subjective, evaluative, and independent of the sensations, thoughts, or images evoking them". The term feeling is closely related to, but not the same as, emotion. Feeling may, for instance, refer to the conscious subjective experience of emotions. The study of subjective experiences is called phenomenology. Psychotherapy generally involves a therapist helping a client understand, articulate, and learn to effectively regulate the client's own feelings, and ultimately to take responsibility for the client's experience of the world. Feelings are sometimes held to be characteristic of embodied consciousness.

Empathy is generally described as the ability to take on another person's perspective, to understand, feel, and possibly share and respond to their experience. There are more definitions of empathy that include but are not limited to social, cognitive, and emotional processes primarily concerned with understanding others. Often times, empathy is considered to be a broad term, and broken down into more specific concepts and types that include cognitive empathy, emotional empathy, somatic empathy, and spiritual empathy.

Gabriel Tarde was a French sociologist, criminologist and social psychologist who conceived sociology as based on small psychological interactions among individuals, the fundamental forces being imitation and innovation.

Sex differences in psychology are differences in the mental functions and behaviors of the sexes and are due to a complex interplay of biological, developmental, and cultural factors. Differences have been found in a variety of fields such as mental health, cognitive abilities, personality, emotion, sexuality, friendship, and tendency towards aggression. Such variation may be innate, learned, or both. Modern research attempts to distinguish between these causes and to analyze any ethical concerns raised. Since behavior is a result of interactions between nature and nurture, researchers are interested in investigating how biology and environment interact to produce such differences, although this is often not possible.

Affect theory is a theory that seeks to organize affects, sometimes used interchangeably with emotions or subjectively experienced feelings, into discrete categories and to typify their physiological, social, interpersonal, and internalized manifestations. The conversation about affect theory has been taken up in psychology, psychoanalysis, neuroscience, medicine, interpersonal communication, literary theory, critical theory, media studies, and gender studies, among other fields. Hence, affect theory is defined in different ways, depending on the discipline.

Emotional contagion is a form of social contagion that involves the spontaneous spread of emotions and related behaviors. Such emotional convergence can happen from one person to another, or in a larger group. Emotions can be shared across individuals in many ways, both implicitly or explicitly. For instance, conscious reasoning, analysis, and imagination have all been found to contribute to the phenomenon. The behaviour has been found in humans, other primates, dogs, and chickens.

Affect, in psychology, is the underlying experience of feeling, emotion, attachment, or mood. It encompasses a wide range of emotional states and can be positive or negative. Affect is a fundamental aspect of human experience and plays a central role in many psychological theories and studies. It can be understood as a combination of three components: emotion, mood, and affectivity. In psychology, the term affect is often used interchangeably with several related terms and concepts, though each term may have slightly different nuances. These terms encompass: emotion, feeling, mood, emotional state, sentiment, affective state, emotional response, affective reactivity, disposition. Researchers and psychologists may employ specific terms based on their focus and the context of their work.

Psychological anthropology is an interdisciplinary subfield of anthropology that studies the interaction of cultural and mental processes. This subfield tends to focus on ways in which humans' development and enculturation within a particular cultural group—with its own history, language, practices, and conceptual categories—shape processes of human cognition, emotion, perception, motivation, and mental health. It also examines how the understanding of cognition, emotion, motivation, and similar psychological processes inform or constrain our models of cultural and social processes. Each school within psychological anthropology has its own approach.

The theory of constructed emotion is a theory in affective science proposed by Lisa Feldman Barrett to explain the experience and perception of emotion. The theory posits that instances of emotion are constructed predictively by the brain in the moment as needed. It draws from social construction, psychological construction, and neuroconstruction.

Emotions are biocultural phenomena, meaning they are shaped by both evolution and culture. They are "internal phenomena that can, but do not always, make themselves observable through expression and behavior". While emotions themselves are universal, they are always influenced by culture. How they are experienced, expressed, perceived, and regulated varies according to cultural norms and values. Culture is a necessary framework to understand global variation in emotion.

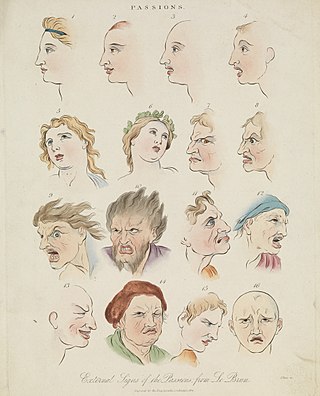

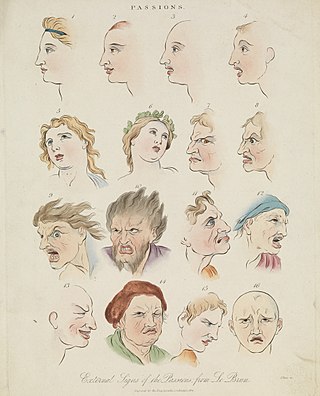

Discrete emotion theory is the claim that there is a small number of core emotions. For example, Silvan Tomkins concluded that there are nine basic affects which correspond with what we come to know as emotions: interest, enjoyment, surprise, distress, fear, anger, shame, dissmell and disgust. More recently, Carroll Izard at the University of Delaware factor analytically delineated 12 discrete emotions labeled: Interest, Joy, Surprise, Sadness, Anger, Disgust, Contempt, Self-Hostility, Fear, Shame, Shyness, and Guilt.

The Sociology of emotions applies a sociological lens to the topic of emotions. The discipline of Sociology, which falls within the social sciences, is focused on understanding both the mind and society, studying the dynamics of the self, interaction, social structure, and culture. While the topic of emotions can be found in early classic sociological theories, sociologists began a more systematic study of emotions in the 1970s when scholars in the discipline were particularly interested in how emotions influenced the self, how they shaped the flow of interactions, how people developed emotional attachments to social structures and cultural symbols, and how social structures and cultural symbols constrained the experience and expression of emotions. Sociologists have focused on how emotions are present in the creation of social structures and systems of cultural symbols, and how they can also play a role in deconstructing social structures and challenging cultural traditions. In this case, in order to understand the mind, affect and rational thought must be considered since humans find motivation among non-rational factors such as levels of emotional commitment to norms, values, and beliefs. Within sociology, emotions can be seen as social constructs that are fabricated by interaction and collaboration between human beings. Emotions are a part of the human experience, and they gain their meaning from a given society's forms of knowledge.

The sociology of the Internet involves the application of sociological or social psychological theory and method to the Internet as a source of information and communication. The overlapping field of digital sociology focuses on understanding the use of digital media as part of everyday life, and how these various technologies contribute to patterns of human behavior, social relationships, and concepts of the self. Sociologists are concerned with the social implications of the technology; new social networks, virtual communities and ways of interaction that have arisen, as well as issues related to cyber crime.

Jussi Ville Tuomas Parikka is a Finnish new media theorist and Professor in Digital Aesthetics and Culture at Aarhus University, Denmark. He is also (visiting) Professor in Technological Culture & Aesthetics at Winchester School of Art as well as visiting professor at FAMU at the Academy of Performing Arts in Prague. In Finland, he is Docent of digital culture theory at the University of Turku. Until May 2011 Parikka was the Director of the Cultures of the Digital Economy (CoDE) research institute at Anglia Ruskin University and the founding Co-Director of the Anglia Research Centre for Digital Culture. With Ryan Bishop, he also founded the Archaeologies of Media and Technology research unit.

Social contagion involves behaviour, emotions, or conditions spreading spontaneously through a group or network. The phenomenon has been discussed by social scientists since the late 19th century, although much work on the subject was based on unclear or even contradictory conceptions of what social contagion is, so exact definitions vary. Some scholars include the unplanned spread of ideas through a population as social contagion, though others prefer to class that as memetics. Generally social contagion is understood to be separate from the collective behaviour which results from a direct attempt to exert social influence.

Viral phenomena or viral sensations are objects or patterns that are able to replicate themselves or convert other objects into copies of themselves when these objects are exposed to them. Analogous to the way in which viruses propagate, the term viral pertains to a video, image, or written content spreading to numerous online users within a short time period. This concept has become a common way to describe how thoughts, information, and trends move into and through a human population.

Media archaeology or media archeology is a field that attempts to understand new and emerging media through close examination of the past, and especially through critical scrutiny of dominant progressivist narratives of popular commercial media such as film and television. Media archaeologists often evince strong interest in so-called dead media, noting that new media often revive and recirculate material and techniques of communication that had been lost, neglected, or obscured. Some media archaeologists are also concerned with the relationship between media fantasies and technological development, especially the ways in which ideas about imaginary or speculative media affect the media that actually emerge.

Garnet Hertz is a Canadian artist, designer and academic. Hertz is Canada Research Chair in Design and Media Art and is known for his electronic artworks and for his research in the areas of critical making and DIY culture.

Giuliana Bruno is a scholar of visual art and media. She is currently the Emmet Blakeney Gleason Professor of Visual and Environmental Studies at Harvard University. She is internationally known as the author of numerous influential books and articles on art, architecture, film, and visual culture.