Treaty of Franklin, 1830

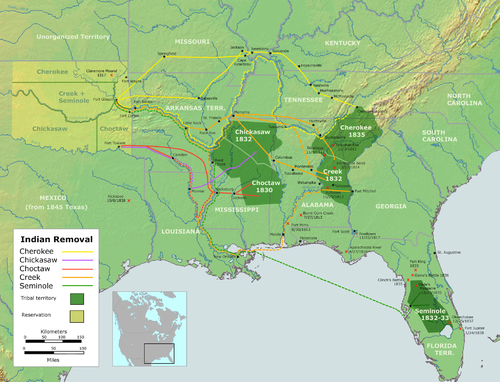

After the act, Jackson received strong legal and judicial resistance from the more law-savvy Creeks and Cherokees, and the Choctaw Chief Greenwood LeFlore furiously refused any meeting with the president. However, the Chickasaw agreed to meet him in Franklin, Tennessee in the summer of 1830. [8] By this point, the State of Mississippi had taken the same measures in dealing with the Chickasaw and Choctaw Indians as Georgia had with the Cherokee, essentially forbidding any exercise of tribal governance and extending state law over the Chickasaw Nation's borders. The Chickasaw came to Franklin to appeal to Jackson for Federal protection from Mississippi. Jackson, however, successfully talked the chiefs into removal after suggesting that by remaining in Mississippi, the Chickasaw would become subject to Mississippi law and their culture would eventually be extinguished by the incursion of white settlers. He said: "By becoming amalgamated with the whites, your national character will be lost... you must disappear and be forgotten." [9] On August 27, 1830, after four days of deliberation, the Chickasaw chiefs agreed to exchange their land in Mississippi and relocate to the west. [9]

Renegotiation and Pontotoc Creek

A Chickasaw delegation assigned to explore the new Chickasaw territory west of the Mississippi stalled removal, much to Jackson's distress, for another two years. They returned to the Mississippi Chickasaw and said that the new land was unacceptable for their people. The Senate refused to ratify the Franklin treaty and the Chickasaw refused to leave their territory in Mississippi. [10] For two additional years, the Chickasaws remained in Mississippi. Increasingly, however, the resolve of the Chickasaw people began to wane due to increasing numbers of non-Chickasaw squatters on Chickasaw lands and the passage of Mississippi state laws which challenged Chickasaw self-governance. In 1832, the Chickasaw National Council agreed to meet with John Coffee to negotiate a land transfer treaty. On October 20, 1832, during a meeting at the Council House on Pontotoc Creek, Chickasaw leaders signed a treaty allowing for the sale of Chickasaw lands within the state of Mississippi, in exchange for the surveying of new lands in the west. [10]

The preamble written by the Chickasaw chiefs read:

The Chickasaw Nation find themselves oppressed in their present situation, by being made subject to the laws of the States in which they reside. Being ignorant of the laws of the white man, they cannot understand or obey them. Rather than submit to this great evil, they prefer to seek a home in the west, where they may live and be governed by their own laws. And believing that they can procure for themselves a home, in a country suited to their wants and condition, provided they had the means to contract and pay for the same, they have determined to sell their country and hunt a new home. The President has heard the complaints of the Chickasaws and like them believes they cannot be happy, and prosper as a nation, in their present situation and condition, and being desirous to relieve them from the great calamity that seems to await them, if they remain as they are - He has sent his Commissioner General John Coffee, who has met the whole Chickasaw nation in Council, and after mature deliberation, they have entered into the following articles... [11]

Although further complications had to be resolved, Arrell M. Gibson writes that the Pontotoc Creek Treaty "was the basic Chickasaw removal document providing for the cession of all tribal land east of the Mississippi River." [12] In the treaty, the Chickasaw land was ceded in return for the U.S. finding suitable land for resettlement –revealing the chiefs' desperation to regain Chickasaw sovereignty from the aggressions of the state of Mississippi. [13] Chickasaw landholders were to be compensated for the improvements made on their lands, and all the proceeds made by the Federal government in the sale of the land were to be turned over to the Chickasaw to pay for finding new territory and the actual removal of the tribe. Unlike in other removal treaties, the Chickasaw would pay for their own migration. [14] The treaty also provided for protection the Chickasaw in Mississippi until they emigrated with the allotment of "temporary homesteads." This meant that the Chickasaws were allotted the land they were living on in Mississippi, to be protected by the Federal government from squatters; this benefit was not given to the Cherokee when later the Federal government relied on the influx of squatters in Georgia to pressure the Cherokee into removal. [14]