Judaism is an Abrahamic, monotheistic, and ethnic religion comprising the collective religious, cultural, and legal tradition and civilization of the Jewish people. It has its roots as an organized religion in the Middle East during the Bronze Age. Modern Judaism evolved from Yahwism, the religion of ancient Israel and Judah, by the late 6th century BCE, and is thus considered to be one of the oldest monotheistic religions. Judaism is considered by religious Jews to be the expression of the covenant that God established with the Israelites, their ancestors. It encompasses a wide body of texts, practices, theological positions, and forms of organization.

Jewish prayer is the prayer recitation that forms part of the observance of Rabbinic Judaism. These prayers, often with instructions and commentary, are found in the Siddur, the traditional Jewish prayer book.

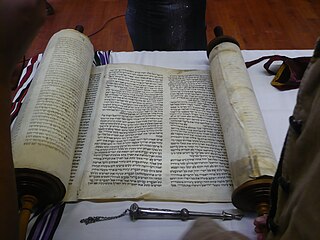

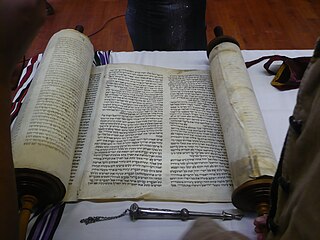

The Torah is the compilation of the first five books of the Hebrew Bible, namely the books of Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers and Deuteronomy. In that sense, Torah means the same as Pentateuch or the Five Books of Moses. It is also known in the Jewish tradition as the Written Torah. If meant for liturgic purposes, it takes the form of a Torah scroll. If in bound book form, it is called Chumash, and is usually printed with the rabbinic commentaries.

A rabbi is a spiritual leader or religious teacher in Judaism. One becomes a rabbi by being ordained by another rabbi – known as semikha – following a course of study of Jewish history and texts such as the Talmud. The basic form of the rabbi developed in the Pharisaic and Talmudic eras, when learned teachers assembled to codify Judaism's written and oral laws. The title "rabbi" was first used in the first century CE. In more recent centuries, the duties of a rabbi became increasingly influenced by the duties of the Protestant Christian minister, hence the title "pulpit rabbis", and in 19th-century Germany and the United States rabbinic activities including sermons, pastoral counseling, and representing the community to the outside, all increased in importance.

There is no established formulation of principles of faith that are recognized by all branches of Judaism. Central authority in Judaism is not vested in any one person or group - although the Sanhedrin, the supreme Jewish religious court, would fulfill this role if it were re-established - but rather in Judaism's sacred writings, laws, and traditions.

Torah study is the study of the Torah, Hebrew Bible, Talmud, responsa, rabbinic literature, and similar works, all of which are Judaism's religious texts. According to Rabbinic Judaism, the study is done for the purpose of the mitzvah ("commandment") of Torah study itself.

It is a custom among religious Jewish communities for a weekly Torah portion to be read during Jewish prayer services on Monday, Thursday, and Saturday. The full name, Parashat HaShavua, is popularly abbreviated to parashah, and is also known as a Sidra or Sedra.

Torah reading is a Jewish religious tradition that involves the public reading of a set of passages from a Torah scroll. The term often refers to the entire ceremony of removing the scroll from the Torah ark, chanting the appropriate excerpt with special cantillation (trope), and returning the scroll(s) to the ark. It is also commonly called "laining".

Va'eira, Va'era, or Vaera is the fourteenth weekly Torah portion in the annual Jewish cycle of Torah reading and the second in the Book of Exodus. It constitutes Exodus 6:2–9:35. The parashah tells of the first seven Plagues of Egypt.

Pekudei, Pekude, Pekudey, P'kude, or P'qude is the 23rd weekly Torah portion in the annual Jewish cycle of Torah reading. It is the 11th and last in the Book of Exodus. The parashah tells of the setting up of the Tabernacle.

Shlach, Shelach, Sh'lah, Shlach Lecha, or Sh'lah L'kha is the 37th weekly Torah portion in the annual Jewish cycle of Torah reading and the fourth in the Book of Numbers. Its name comes from the first distinctive words in the parashah, in Numbers 13:2. Shelach is the sixth and lecha is the seventh word in the parashah. The parashah tells the story of the twelve spies sent to assess the promised land, commandments about offerings, the story of the Sabbath violator, and the commandment of the fringes.

Emor is the 31st weekly Torah portion in the annual Jewish cycle of Torah reading and the eighth in the Book of Leviticus. The parashah describes purity rules for priests, recounts the holy days, describes the preparations for the lights and bread in the sanctuary, and tells the story of a blasphemer and his punishment. The parashah constitutes Leviticus 21:1–24:23. It has the most verses of any of the weekly Torah portions in the Book of Leviticus, and is made up of 6,106 Hebrew letters, 1,614 Hebrew words, 124 verses and 215 lines in a Torah Scroll.

Behar, BeHar, Be-har, or B'har is the 32nd weekly Torah portion in the annual Jewish cycle of Torah reading and the ninth in the Book of Leviticus. The parashah tells the laws of the Sabbatical year and limits on debt servitude. The parashah constitutes Leviticus 25:1–26:2. It is the shortest of the weekly Torah portions in the Book of Leviticus. It is made up of 2,817 Hebrew letters, 737 Hebrew words, 57 verses, and 99 lines in a Torah Scroll.

Bechukotai, Bechukosai, or Bəḥuqothai (Biblical) is the 33rd weekly Torah portion in the annual Jewish cycle of Torah reading and the 10th and last in the Book of Leviticus. It constitutes Leviticus 26:3–27:34. The parashah addresses blessings for obeying the law, curses for disobeying it, and vows. The parashah is made up of 3,992 Hebrew letters, 1,013 Hebrew words, 78 verses, and 131 lines in a Torah Scroll.

Pinechas, Pinchas, Pinhas, or Pin'has is the 41st weekly Torah portion in the annual Jewish cycle of Torah reading and the eighth in the Book of Numbers. It tells of Phinehas's killing of a couple, ending a plague, and of the daughters of Zelophehad's successful plea for land rights. It constitutes Numbers 25:10–30:1. The parashah is made up of 7,853 Hebrew letters, 1,887 Hebrew words, 168 verses, and 280 lines in a Torah scroll.

Matot, Mattot, Mattoth, or Matos is the 42nd weekly Torah portion in the annual Jewish cycle of Torah reading and the ninth in the Book of Numbers. It comprises Numbers 30:2–32:42. It discusses laws of vows, the destruction of Midianite towns, and negotiations of the Reubanites and Gadites to settle land outside of Israel.

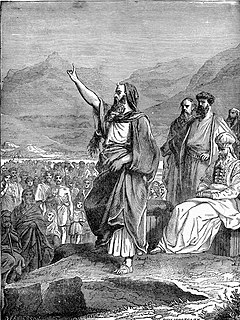

Devarim is the 44th weekly Torah portion in the annual Jewish cycle of Torah reading and the first in the Book of Deuteronomy. It comprises Deuteronomy 1:1–3:22. The parashah recounts how Moses appointed chiefs, the episode of the Twelve Spies, encounters with the Edomites and Ammonites, the conquest of Sihon and Og, and the assignment of land for the tribes of Reuben, Gad, and Manasseh.

Vayelech, Vayeilech, VaYelech, Va-yelech, Vayelekh, Wayyelekh, Wayyelakh, or Va-yelekh is the 52nd weekly Torah portion in the annual Jewish cycle of Torah reading and the ninth in the Book of Deuteronomy. It constitutes Deuteronomy 31:1–30. In the parashah, Moses told the Israelites to be strong and courageous, as God and Joshua would soon lead them into the Promised Land. Moses commanded the Israelites to read the law to all the people every seven years. God told Moses that his death was approaching, that the people would break the covenant, and that God would thus hide God's face from them, so Moses should therefore write a song to serve as a witness for God against them.

An aliyah is the calling of a member of a Jewish congregation up to the bimah for a segment of the formal Torah reading.

A seder is part of a biblical book in the Masoretic Text of the Hebrew Bible.